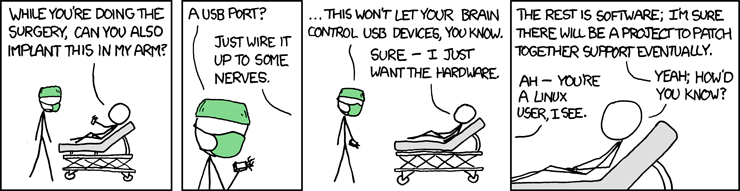

As a follow-up to Michael Haycock’s clarification of what it means to be a Mormon priest or bishop, I did a two-part Q&A about Mormon theology, hierarchy, and culture. My questions are in bold, his answers follow, and he has no culpability for my choice of pictures.

Q: Why is the Melchizedek Priesthood reserved to men? Are there any roles reserved to women?

Hoo boy. The first question is a loaded one, because it cuts to the quick of the issue of Mormonism and gender, on which you might be able to adapt the Jewish adage to Mormons: two Mormons, three opinions. Some will say it’s a relic of 19th Century social normativity further reinforced by the post-WWII culture; some will say it’s divinely inspired and tailored to the inherent strengths and weaknesses of the respective sexes; some will say women are so spiritually inclined that they don’t need leadership positions to teach them how to be that way.

Me? I’d say I don’t know. Maybe it will change in the future, but I won’t pretend to have foreknowledge.

The official LDS Church response to the second question would be (and has been) “Of course!” While that is technically true, it needs some qualification.

Women can be called to many positions, from teaching to family history consultant to Cubmaster (Cub Scouts leader). However, there are many positions exclusively reserved for men (including some that are a little baffling) and those that are exclusively reserved for women are mostly either 1) overseeing fellow females or 2) seemingly based on stereotypical gender roles and perceptions. Included in these are positions in the Relief Society, the organization that incorporates the women of the LDS Church; Young Women, which serves girls ages 12-18 (and mirrored by its male counterpart organization, Young Men); and Primary, the organization that cares for children in the church. In the past, many of these organizations had a huge degree of autonomy: they had their own budgets and regional bulletins, and generally ran genuinely parallel to the male hierarchy.

However, as the LDS Church began to greatly expand outside of the American Mountain West in the 1950s and 60s, the patchwork organization of the Church, many times based on neighborliness and kinship, was deemed no longer robust enough to maintain international unity. In a long process known as Correlation, Church curricula were standardized, the ecclesiastical hierarchy clarified and streamlined, and the women’s organizations were brought under greater direct Priesthood (read: male) supervision and direction, among other sundry things, reducing ecclesiastical autonomy for women.

That said, oftentimes the woman-specific positions are incredibly influential, although your mileage may vary based on the degree of traditionalism in the local leadership that oversees these positions. In my home ward, for example, the Relief Society president is delegated most of the responsibility for administering welfare funds. So yes, there is some position for women to influence the Church. Many are satisfied with that. Many are not.

Q: Why do you think the Mormon church labels the open-to-all-men category as a ‘priesthood?’ What makes it different from other growing-older-and-affirming-commitment transitions like confirmation in the Catholic Church and bar/bat mitzvahs?

Historians would probably say that it’s a radical outgrowth of the Protestant “priesthood of all believers” conception. However, having grown up Mormon, I don’t see why the category of “priesthood” would depend on it being an exclusionary group (and I would love to hear how you got that perception). One of the ideas is that God disperses His power so that it can be shared as widely as possible. And since all men are given that authority to be priests – to act, in some degree, in God’s place – the terminology comes with it. Another LDS conception is that God wanted to make ancient Israel a “nation of priests and kings” and could not; with the LDS Church, he’s preparing us to fulfill that postponed divine desire.

I also have to admit that I’m not sure exactly what significance confirmation and bar/bat mitzvahs have in their respective traditions. Perhaps the biggest difference is that such transitions in the LDS faith are not usually celebrated. They generally pass quietly; one Sunday, a 12-year-old boy is interviewed, and the next, he is ordained, ready to participate in the officiation of the Sacrament (LDS version of communion/Eucharist, basically). It’s supposed to be a time of added responsibility (that’s when boys and girls can first receive callings to preside over their peer age groups), but the sometimes the biggest shift is that they start going to the classroom of another age group.

In fact, I think LDS baptism would be the closest to those. For children, even if they’ve been raised LDS, the earliest they can get baptized is age eight. Since a baptism doesn’t fit into the regular Sunday meeting schedule (as do Priesthood ordinations, for example) and instead get its own service, there’s more attention given to them. And even though LDS children are listed in church records from birth, it’s when they’re baptized that they’re actually considered full members, accountable for their sins.

Q: What determines whether an eight-year-old is ready to accept baptism? From discussions of posthumous baptism, I thought baptism in LDS is mainly a prerequisite to everything else not something that necessarily changes you in and of itself. Why not baptize infants?

An eight-year-old receives an interview with her bishop in which he ascertains that her beliefs, commitments, and understanding of baptism are appropriate; children are instructed to prepare for this time as much as they can. If the bishop deems the child unprepared, the baptism could be postponed. In some cases – especially in cases of severe mental disability – baptism is actually regarded as unnecessary because the person, not having a consciousness of right or wrong (and thus free of sin) or a comprehension of the significance of baptism, is regarded as not needing the forgiveness made possible by adherence to the covenants made at baptism.

The thought concerning baptism for the dead is a tad different in that respect from baptism for the living. Because of the impossibility of getting consent from the deceased, we cannot assume they’ve given it; it is thus seen as something that can been rejected (leaving it as if it had never been performed). There might be people, though, who would consent, and for them, it’s necessary that the ordinance be performed in the flesh, with a living body (hence, by living proxies – and here again we get the importance of the material body!). The idea of the baptism’s efficaciousness being contingent on consent is constant, but practicality rules out the possibility of ascertaining consent in the case of the dead (we don’t hold seances, after all). In fact, in the cases in which we know that the dead died under the age of eight, there are actually no baptisms performed or their behalf.

For other questions on infant baptism, I’d refer you to Moroni 8 in the Book of Mormon. On baptism for the dead, Joseph Smith’s words on the subject are in Doctrine and Covenants 128.