This post is part of a series discussing Daniel Dennett’s Breaking the Spell.

By the end of Breaking the Spell, Dennett has shown the reader that religions may have memetic staying power independent of their truth. And, even if a religious reader isn’t convinced that their own religion is explained away by evolutionary processes, he hopes his book will awaken the religious to their unique duty to short-circuit dangerous religious memes. He writes:

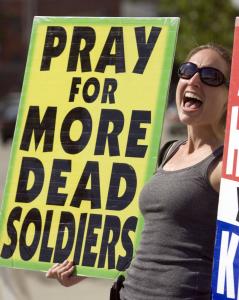

“There is more work to be done, and it is the unpleasant and even dangerous work of desanctifying the excesses in each tradition from the inside. Any religious person who is not actively and publicly involved in that effort is shirking a duty–and the fact that you don’t belong to a congregation or denomination that is offending doesn’t excuse you: it is Christianity and Islam and Judaism and Hinduism (for example) that are attractive nuisances, not just their offshoot sects.”

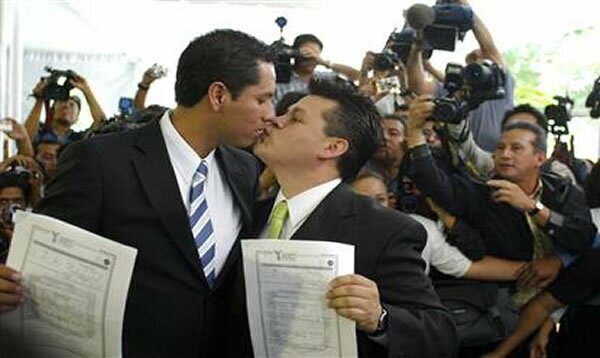

I love duties and I love arguments, so a duty to pick fights is awfully tempting. But I think Dennett’s exhortation is misguided. I’m not a adept in every style of fight or theology. I might know enough to not subscribe to a philosophy without being fluent enough to persuade its adherents to give it up. There’s a lot of distance between points, even if you limit yourself to Christian conceptspace.

If I can’t speak to my opponents, speaking about them to condemn them is of limited use.

There needs to be enough public disapproval for people stuck within a bad institution to understand its precepts aren’t universally acclaimed and to have a sense of why. But every Christian doesn’t need to speak about each bad sect to accomplish this.

Condemning outside of conversation with your enemy can be counterproductive. If I speak in the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. I like to try and keep my interlocutors face before me in a fight, so I have to remember I’m fighting a person and that all my work has to be for their good, not an excuse to feel superior that I didn’t fall into that error.

But why shouldn’t I spend more time training up to fight the people I can’t reach now? Why not spend more of my blogging time rebuking bad theology and less time gushing over Stephen Sondheim. Accepting the duty Dennett proposes gives the people in error too much power over us. I’m reminded of the story of the Tragedian in C.S. Lewis’s The Great Divorce:

“That sounds very merciful: but see what lurks behind it… The demand of the loveless and the self-imprisoned that they should be allowed to blackmail the universe: that till they consent to be happy (on their own terms) no one else shall taste joy: that theirs should be the final power; that Hell should be able to veto Heaven.”

That’s why my comment policy makes it clear that I don’t take on the responsibility of responding to or deleting every aggressive comment. Where we can intervene to protect others from harm, we should, but rebuking other people’s beliefs shouldn’t be able to preempt explaining and living our own.