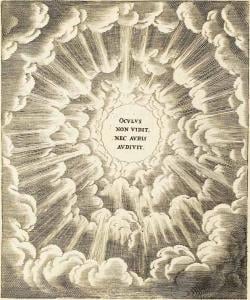

God is both transcendent and immanent, transcending all things and yet found in and able to be experienced through all things:

He is outside of all things and within all things; He comprises all things and is comprised by none; He does not change either by increase or decrease, but is invisible, incomprehensible, complete, perfect, and eternal; He does not know anything from elsewhere, but He Himself is sufficient unto Himself to remain what He is.[1]

God’s transcendence makes God incomprehensible to us. God’s immanence makes God apprehensible to us. This means that we can both convey truths about God, thanks to the fact God is apprehensible to us, but also that the absolute truth of God the divine nature is in itself is outside of what we can ever say about God. We are not denied a way of knowing God, but we must not confuse the truth which we come to know, the truth which we apprehend, with the fullness of who and what God is. What we speak about God, the theological reflections which come as a result of our apprehensions of God (that is, from what God reveals to us), is labeled kataphatic theology; theology which explore the way the divine nature transcends what can said about God, reminding us the limits of human language and all theological constructs, is labelled apophatic theology.

Embracing a kataphatic theology without an apophatic caveat can easily lead us astray, making us think we can comprehend that which is not comprehensible; we would end up turning the conventional truths that flow from our apprehensions of God into absolutes, claiming in and through them, we have attained the fullness of who and what God is. It would suggest that not only is God comprehensible to us, but, by such comprehensibility, we are either God’s equals or superiors. Apophatic theology, on the other hand, can easily be abused, and turn into a form of nihilism, because it would have us deny the value of kataphatic theology, and with it, conventional truth. We would end up saying we can know nothing about God, and any attempt to talk about God is equally as false as calling a dog a cat.

Conventional truth is the truth as it can be apprehended by us, either through our natural reason or through revelation; to absolutely deny it is to deny the truth which inspired it, which means, a denial of the absolute truth itself. This is why great apophatic theologians always make sure we do not confuse apophaticism in such a way. They know that if we do, we would end up becoming nihilists. They tell us that the apophatic way is a tool which is meant to preserve and protect the absolute truth and not deny it, and if the absolute truth exists, and is known to exist, then, in relation to the way it acts in and with us, we can engage it and apprehend something about it (this realizations is what led St. Gregory Palamas to talk about the divine energies of God, pointing out we know God through God’s actions, not God’s essence). The apophatic way, as Fr. George Maloney explained, is meant to help remove all the dross which gets in our way of our experience of God, and not to deny that experience or what we can say as a result of it; indeed, it is meant to affirm that experience:

Apophatic is usually thought of as a “negative” approach, an approach which denies that rational knowledge is the only knowledge we can have of God. Actually, however, the apophatic approach is much more than that. It opens us up to a “positive” experiential knowledge of God. This is an infused knowledge given by God to those who are “pure of heart.” Through it they “see” or “experience” God in the “luminous darkness” of faith, hope and love.[2]

Apophatic theology and its methodology is meant to preserve and protect the transcendence of God, as well as preserve and protect God’s ability to interact with and engage us:

There is the positive, dialectical side to the apophatic theology of the Eastern Fathers. The Incomprehensible One is present and is experienced by the Christians. It is this very presence that is spoken of. It is that very transcendence that brings darkness to man’s own reasoning powers. The emphasis is not on the incapacity but rather on the overwhelming infinity of God that is nevertheless present.[3]

The apophatic way tells us to properly experience God, to gain more apprehension of God, we must silence our thoughts, and with such silence, not contemplate or think about all the conventional truths we have apprehended, for if we do not do so, our thoughts will get in the way of new experiences with God It is only when we engage such silence, will we be ready to listen to God when God comes to “speak” with us in our silence:

We cannot speak of ultimate truth and express it in our concepts, but this is only because the ultimate truth itself speaks, wordlessly, for itself and of itself, expresses and reveals itself. And we have neither the right nor the possibility to full express through our thinking this self-revelation of ultimate truth. We must be silent before the magnificence of truth itself.[4]

The more we open ourselves up to God’s transcendent mystery, the more we take the time to silence ourselves and come before God in such silence, the more we will be able to experience God, allowing us to apprehend more and more of God. After such experiences, we must reflect on what we have gained, and consider how it complements the apprehensions and conventions we already had. That is, we will go from the apophatic silence to kataphatic theology. If we ever think we have attained all that is possible to attain, that we have comprehended God, we will cut ourselves off from the transcendent mystery of God. Our understanding not only will have us come to believe in and follow a limited God, because our image of God will not be who God really is, we will end up having created an idol for ourselves. As long as we hold onto that idol, we will deny ourselves the greater truth and presence of God, and the growth which comes from that presence:

Where are those who say they have attained and possess the fullness of knowledge? The fact is that they have really fallen into the deepest ignorance. For people who say that they have attained the totality of knowledge in the present life are only depriving themselves of perfect knowledge for the life hereafter. As for me, I say that my knowledge is imperfect and incomplete. And if I say that this knowledge will pass away, I am advancing on the road to a better and more perfect state. There, the partial knowledge becomes a more perfect knowledge once what was partial and imperfect has passed away.[5]

Apophatic theology is important, as it points us to the transcendent mystery of God; we must always keep that mystery intact, for by it, we will be able to constantly grow in knowledge and understanding of God. We will find ourselves constantly experiencing God anew. It reminds us that as conventions should not be seen as absolutes, our engagement with our conventions must reflect that, that is, we should never treat them as literal: they are metaphoric, pointing beyond the conventions themselves, pointing to a truth which transcends the words used to present that truth. That is, we must embrace the spirit, not the letter, of the conventions. So long as we keep this in mind, kataphatic theology serves a vital role and must never be absolutely denied.

[1] St. Hilary of Poitiers, The Trinity. Trans. Stephen McKenna, CSSR (New York: Fathers of the Church, Inc., 1954), 66.

[2] George A. Maloney, SJ, Called To Be Free (New York: Alba House, 2001), 4.

[3] George Maloney, SJ, God’s Exploding Love (New York: Alba House. 1987), 56.

[4] S. L. Frank, The Unknowable: An Ontological Introduction To The Philosophy of Religion. Trans. Boris Jakim (Brooklyn, NY: Angelico Press, 2020), 96.

[5] St. John Chrysostom, On the Incomprehensible Nature of God. Trans. Paul W. Harkins (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1982), 58 [Homily 1].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.