Too many Catholics misunderstand the eucharist, not because they reject the real presence, but because they have ignored the main purpose of communion. We are called to share in the life of Christ, to have Christ residing in us (and us in Christ), which happens when we partake of the eucharist.

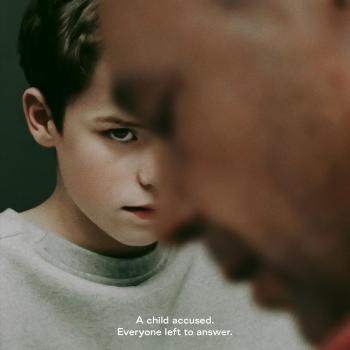

The eucharist is spiritual food; we are told to eat it. Jesus did not tell us to set it aside in some corner and have it act as some sort of totem, keeping it separate from us. The eucharist is the bread of life; through it, we become partakers of the divine nature and eternal life. We are called to become christs in Christ; then, we are meant to continue the work of the incarnation, bringing restorative justice and reconciliation to the world. We are called to promote healing for those who have suffered grave harm, and to do that, we must be willing to listen to and elevate those in need over and above those who have undermined them and sinfully subjugated them:

Within the eucharist, partaking of daily nourishment is to partake in Christ’s sacrifice, to partake in that death of individual demands and claims which raises life up into the miracle of communion. The bread and wine of the eucharist are the body and blood of Christ, the reality of His theanthropic nature – a participation and communion in His mode of existence. It is the first-fruits or leaven of life, for the transfiguration of every facet, every activity in human life into an opportunity for communion and an event of communion. [1]

The eucharist is food, and we are to become what we eat. We should not set it aside, keeping ourselves distant from Christ, thinking if we just bow down and honor him at a safe distance, we satisfy Christ and what he wants from us. How can we adore him, how can we say we love him, if we ignore him and what he has told us to do? The way eucharistic adoration has developed, the way many of the faithful consider it, sometimes undermines communion, for it ends up keeping Christ distant from those who should receive him and his graces. What started as a good discipline has been abused. The eucharist is primarily food, and through it we are to become one with Christ and all who have been incorporated into him. Why do we focus on the way the eucharist can be kept separate from us, having it seem we are not one with Christ? For this reason, many Eastern Christians have stated concerns they have related to eucharistic adoration, some of which Archbishop Raya summarizes when he wrote:

Our Church believes that in the Holy Eucharist, the real presence of Christ in the bread and wine is for eating and drinking only. It is reserved for this most mysterious and most glorious union with the Lord Jesus Christ. It cannot be looked upon or talked to; yet it is adored. The icon is for visiting and for person-to-person conversations because in the icon we see a human face and we encounter a human person. A face is for personal relation and personal dialogue.[2]

Again, this is not to say there is not room for the Western development in regards eucharistic adoration, but it needs to be presented better, making sure it does not end up being the main way people engage the eucharist. The eucharist should not be set aside to keep people away from partaking of communion, making them think the main way we are to engage Christ in the eucharist is bow down and pray to him through it. Just as we would not put aside bread and look at it when we are hungry, being thankful the bread is there without partaking of it, so we should not set Christ aside, being thankful he is there, while denying our spiritual hunger and our need for communion. The eucharist was instituted to give us the bread of life, to give us the spiritual food and drink which we need. We are called to receive, to partake of Christ; we must not set him aside, keeping him outside of us, addressing him as some sort of magic genie, demanding him to fulfill our every whim. We are called to welcome him into ourselves, to open ourselves to him, to join our will with his will as we become one with him.

Through our communion with Christ, we can find him in ourselves. We are not meant to engage the eucharist and eucharistic theology merely by discussing the eucharist, explaining how and why we think it is Christ who comes to us in the appearance of bread and wine, thinking that is the extent of eucharistic teaching; rather, we are to experience Christ within, to find that Christ is teaching us and enlightening us in and through its reception, teaching us in ways which transcend our intellectual abilities:

Dogmatic, speculative theology can give us distinctions between substance and accidents and work out for us a theory of transubstantiation. It is, however, only in the immediate experience of celebrating the Eucharist and in receiving the Bread of Life that we come into a resolution of the antinomies of how eternity and time can meet, how Divinity can be joined with humanity, how Jesus Christ is both true God and true man eternally in glory and yet always coming into our lives to touch our human bodies with His glorious Body and Blood. Here we experience how we are Church, many members and yet each member uniquely loved by God, waiting for the full eschaton to come and yet in the Eucharist it has begun.[3]

When we set the eucharist aside, when we set Christ aside to be adored, making our engagement with Christ as if Christ is something and someone who is absolutely outside of us, we have undermined the purpose behind the institution of the eucharist. The church is meant to be built up by having us transcend barriers, not making more of them. Keeping him apart from us creates and reifies those barriers, reifies, indeed, an individualistic and dualistic approach to existence. The truth is that the world and all that is in it is meant to be one, not in some sort of monistic annihilation of distinction, but in a way which allows for a plurality in that unity. Our personal existence is to be affirmed as we become persons in Christ, where we find our personal uniqueness is affirmed. We are meant to be a community, and that community is undermined if we deny the unique gift of everyone who is a part of it. We need each other. We need to realize our oneness with everyone, and with the whole of creation. Sin has divided us, and continues to create more and more walls between us, the more we give in to it. Christ in the incarnation came to break down those barriers, and he set a way to reestablish the lost unity in and through his self-giving sacrifice. Christ gives us himself, the gift of himself, in communion, and we, then, are to follow suit, giving the gift of ourselves to others in communion as well. The eucharist is meant to serve as the means by which our unity is strengthened, but sadly, the way we often treat it, our actions often end up engaging the eucharist in a way which undermines that purpose.

[1] Christos Yannaras, The Freedom of Morality. Trans. Elizabeth Briere (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1984), 217.

[2] Archbishop Joseph Raya, The Abundance of Love: The Incarnation and Byzantine Tradition (Combermere, ON: Madonna House Publications, 1989; 3rd ed.: 2016), 78.

[3] George Maloney, SJ, God’s Exploding Love (New York: Alba House. 1987), 61.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.