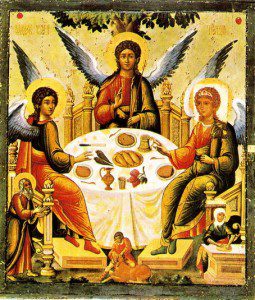

Christian personalism is founded upon and engages what is learned from the teaching of the Trinity. As the name suggests, personalism engages the category of the person. Fundamental to its presentation is the belief that a person does not exist outside of a relationship with other persons. This is true, not only in humanity, but in the divinity. The eternal relations of the three persons of the Trinity confirm that God is not some impersonal divine force. Christian personalism, seeing that there is no person who can exist as a person without some other person to be in relationship with, rejects individualism because individualism leads people to split apart from each other and try to exist as independent entities. However, this is also why personalism rejects collectivism, because it see collectivism as trying to have the persons absorbed by some collective, impersonal whole. As individualism and collectivism end up rejecting and destroying persons, they both lead to destructive ends.[1] The teaching of the Trinity helps show us the way beyond both errors because it explains that persons can and should come together as one united whole without denying or destroying the persons involved:

For, it is impossible in any way to think of a severance or a division, so that the Son is considered apart from the Father, or the Spirit is separated from the Son; but there is found in them a certain inexpressible and incomprehensible union and distinction, since neither the difference of the persons breaks the continuity of the nature, nor the common attribute of substance dissolves the individual character of their distinctive marks.[2]

The oneness of God does not indicate, by itself, that that we need to treat God as if God were but one person. Indeed, if a person is a relational entity, it would be difficult, if not problematic, to describe God as personal if there were only one person in the Godhead, because then one would have to ask where God founded another in order to have a relationship with to make God a person. The teaching of the Trinity shows us a way for us to God is personal because we see within the divine nature there are several persons in eternal relations with each other. Their unity, however, is such that the divine nature is not divided into parts. That is, the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are not parts of God, but rather, each is fully God. God cannot be divided into parts. Wherever one person of the Trinity is found, the fullness of God is to be found (which of course, means the rest of the Trinity will also be able to be found, thanks to their relationship with the other Trinitarian persons).

The created order reflects the unity of the Trinity in that the created order itself can and does establish one whole, a unity which is composed of a plurality of distinctions within it. Nonetheless, there is a difference between the two. Whereas the divine nature cannot be divided into parts, creation can. And if creation is divided, such division not only harms creation, but it creates a void, a void which is otherwise described as evil. For, when creation is divided into parts, each part, though it will try to be self-substantiating, will nonetheless find something lacking in itself, something which is needs from those it has separated itself from. And that lacking will be the source for more evil to emerge, as the void and will grow as the various parts resist restoring their unity with each other.

Individualism, with its attempt to turn persons into independent subjects, promotes and furthers the dissolution of creation, not only by having humanity cut itself off from the rest of creation, but having human persons cut themselves off from each other, dividing humanity into parts as well. Where they once had bonds which connected them with each other, those individuals find more and more of the void connecting and infecting them, for the more they divide themselves from each other, the more they let the void deconstruct and destroy themselves, eating away at the good which they otherwise could and should have had. Instead of trying to heal the void by reestablishing bonds with others, those who promote individualism think the solution lies in finding ways to keep the individual intact. The only way is to fill that void by taking from others, but whatever they take, gets consumed by that void, so that they constantly have to find more and more things to make their own, hoping in that way, they will find the one thing which will satisfy them. This leads each individual to fight against each other, seeking after particular goods for themselves, taking them and making them exclusively theirs. Clearly, this explains why individualists do not know or fight against moral expectations when those expectations tell them to work for and establish the common good. By their continued resistance to the common good, such individualists take away goods from what is to be held in common, leading to the diminishment of the common good. They take private goods at the expense of the common good, some gaining more, others gaining less, all with an attempt to fulfill the void they feel eating away within; nonetheless, the void is never filled, no how matter how much a particular individual takes for themselves. For that void can only be filled by restoring communion with each other, the rest of creation, and with God. This is why Christianity teaches Christians, indeed, humanity as a whole, should work together for the common good; its anthropological understanding is that people are always going to be better, find their lives far more satisfactory, when they experience communion with each other.

Sadly, as a way to combat individualism, there is the ideology of collectivism, one which sees that humanity must be made one, but it misunderstands how this is done, for it thinks the whole must end up becoming impersonal, and in doing so, destroy the persons and the relations and distinctions which persons make in the world. While collectivism certainly overcomes one of the problems of individualism because it promotes the notion of the common good, and works for its establishment, its notion of the common good is insufficient and dangerous. It would be a categorical error to suggest everyone who promotes and works for the common good represent collectivism, just as it would be a categorical error to suggest both dogs and humans are the same because they are both mammals. Promoting the proper kind of unity, one of communion, will promote the common good, but it will do so by pointing out that the persons involved will find they become greater, better, when they work together and promote the common good.

Individualism leads to a dangerous form of egotism, and with it, a false notion of who and what a person is. It thinks an individual is who and what a person is, and in doing so, creates a false identity for the person, one which reifies what the ego suggests as well as the division which it finds between itself and the rest of creation. It suggests that the person, now an individual by itself, can sustain itself in that independence, but the fact that it constantly has to take from others demonstrates how and why this is false. For this reason, that notion of the self, the egotistic, false self, must be rejected (or, in Christian terms, must be put on the cross and left to die). For a person who is trapped by such a false notion of the self must be set free from their individualistic shell. Once the false self, and the barrier it places upon the person, is eliminated, the person can then rise up from the ashes, experiencing, in part, what the resurrection is meant to be.

We must realize, then, as Vladimir Solovyov pointed out, the common good is also the supreme created good (as it includes all other goods with it):

The common good, the supreme good and truth of the world, resides in union of all into one will directed toward the same objects; there is no truth in disagreement and separation, and it is only by co-operation, conscious or unconscious, that the universe is kept in being and carried on. No being can subsist in a state of complete isolation, for such isolation is a falsity, in no degree conformed to the truth of universal unity and peace. [3]

Once again, we can see this demonstrated in and through the Trinity, where the persons of the Trinity, distinct in themselves, do not lose their unity, and with it, they are shown to have one united will. There is no disagreement or separation to be found in the persons of the Trinity, nothing which can or will keep them apart from each other. Where one person of the Trinity is present, all three are present, though all three are present in their own personal way.

The dissolution of the common good, and so the unity of humanity, into individuals is but the beginning of the process of death itself:

For the individual in his egoism declares that he cannot live with other creatures and shuts himself away from the society of them all, thus putting himself in the hellish dilemma, “Either I or they?” He chooses himself, draws the opposition of all the rest upon him, and is destroyed. His whole life is a single slow progress towards dissolution, and death is only an uncovering to the bodily sight of the mystery that the life of nature is only a bidden process of putrefaction. [4]

Thus, the process of salvation requires the restoration of the unity, the unity which has been lost due to selfishness, pride, and other sinful factors which would have human persons disconnecting themselves from their proper relationships with each other. God’s work to save the world, therefore, will work to fix the harm done by the division found in creation, that is, to overcome the harm caused by individualism. The unity of humanity with itself, as well as the unity of humanity with the rest of creation, will be restored:

God thus leads all created beings, all the “particular relations” of the distinct natures, to an unconfused union without abolishing their natural differences. This demonstrates the reference of each one to the wholeness of being, the totality of common, created and caused nature in relation to its one, single, uncreated, and supernatural Cause. God demonstrates, I would say, the consubstantiality of created beings, not by negating the differences of natures, but by joining them without confusion in a harmonious and undivided integrating “identity,” which is ontological because he is “cause, principle, and end of all, the creation and beginning of all things and eternal ground of the circuit of things.” [5]

It is important to keep in mind that God works, not only to reestablish human unity, but the unity which creation is meant to have with itself, that is, to help reestablish the interdependent unity which creation had at its inception. But just as human persons continue to exist in human unity, the distinctions which distinguish elements of creation from each other will be affirmed, as St. Maximos the Confessor indicated “God realizes this union among the natures of things without confusing them but in lessening and bringing together their distinction, as was shown, in relationship and union with himself as cause, principle, and end.”[6]

The promotion of the common good, promotion of unity, and indeed, discussions of the death to the self, must be done in the correct fashion, that is, in such a way to affirm the relative distinctions found in the created order while not allowing this distinctions to become means of separating and dividing that unity into parts. Thus, to achieve such unity, we should not nihilistically destroy the persons involved. Individualism is destructive because it destroys the common good, the base and foundation for the persons to thrive and exists; with that base gone, persons will find themselves going to their own dissolution and death if the common good is not restored. Collectivism engages that common base but becomes destructive as it does not understand how relative distinctions can remain when unity is established. Sadly, we, as a society, have become so used to individualism and its presentation of the person as a mere individual that we see many people fight against the common good, which is why so many assert that any and all attempts for human unity, and with it, the common good, leads to collectivism. But because they are unwilling to think beyond their individualism, they only end up creating a system which will end in their own destruction, as no individual can and will exist by its own power. But, the more they reinforce and reify the individual, apart from the personal relations and unity which emerges from those relations, the more they end of denying and rejecting human subjectivity, for such subjectivity is based upon personal relations and the unity which lies behind those relations. Thus, the more they deny personal subjectivity, the more they will turn themselves into mere objects (and thus, lose the vitality of life itself).

With this understanding, we can understand better the church’s social teaching. While the church acknowledges it cannot and must not try to take control of the political situation, undermining the distinction of church and state, it can and should express what it understands in relation to justice and use that to help make sure the state has the principles it needs to make the proper decisions for itself:

The Church’s social teaching argues on the basis of reason and natural law, namely, on the basis of what is in accord with the nature of every human being. It recognizes that it is not the Church’s responsibility to make this teaching prevail in political life. Rather, the Church wishes to help form consciences in political life and to stimulate greater insight into the authentic requirements of justice as well as greater readiness to act accordingly, even when this might involve conflict with situations of personal interest. Building a just social and civil order, wherein each person receives what is his or her due, is an essential task which every generation must take up anew. As a political task, this cannot be the Church’s immediate responsibility. Yet, since it is also a most important human responsibility, the Church is duty-bound to offer, through the purification of reason and through ethical formation, her own specific contribution towards understanding the requirements of justice and achieving them politically.[7]

The church, therefore, does this, with its promotion of the common good. It shows and explains why humanity must work together to promote the common good, showing that if it does so, everyone can and will benefit from it. And so, as Pope Francis points out, individualism, because it knows of no way to establish community and the bonds humanity needs, will never be able to produce what can and will be found when the common good is affirmed and promoted:

Individualism does not make us more free, more equal, more fraternal. The mere sum of individual interests is not capable of generating a better world for the whole human family. Nor can it save us from the many ills that are now increasingly globalized. Radical individualism is a virus that is extremely difficult to eliminate, for it is clever. It makes us believe that everything consists in giving free rein to our own ambitions, as if by pursuing ever greater ambitions and creating safety nets we would somehow be serving the common good.[8]

Thus, individualism can be seen connected with, and tied, with original sin, and the way sin destroys the unity of humanity. “The essence of the world’s evil is in the fact that human beings feel alien to one another and wallow in discord, contradictions and antipathies, and precisely herein lies the absurd, irrational existence of the world. That is absurd which has no connection with anything else, which is in contradiction with reality or is incompatible with it: evil and absurdity are in essence identical”. [9] Sin tries to cut people off from the connections they can and should have with each other – that is, from love. For it is love which allows people to unite with each other and be one without losing their personal distinctions. This is why marriage is often used as a metaphor to represent the unity humanity is to have with each other and with God, because marriage shows how to can be one while the people involved remain distinct. “Since there exists a double union in marriage, namely a union of hearts and a union of natures in carnal intercourse, correspondingly there will be a double union in spiritual marriage, namely a union in love according to which the soul is made one spirit with God, and a union of natures in the one person of Christ.” [10] Love, or charity, must be the basis we use to form communion with each other, and so acting upon it should also be seen as the foundation by which we establish and promote the common good. “The principle of mutual charity is the perfected form of social life.”[11] But when love is lost, and sin divides and destroys, justice requires fixing and healing the harm which has been caused, for without such healing, love cannot properly form. And so, it is love, moreover, which Christianity preaches, because it sees how such love in God forms the basis of the relations of the Trinity even as it sees such love then can form the basis by which created subjects can remain subjects while united together as one whole. Christian personalism, therefore, reflects upon love, looking at how it can understand how and why love should serve as the basis of our activity in the world. For individualism with individuals cut off from each other, or collectivism with an impersonal collective unity, can and will not know love, as both of them end up denying the persons necessary for such love to exist.

[1] Pope Pius XI, therefore, pointed out how individualism and collectivism are both two shipwrecks to be avoided: “Accordingly, twin rocks of shipwreck must be carefully avoided. For, as one is wrecked upon, or comes close to, what is known as ‘individualism’ by denying or minimizing the social and public character of the right of property, so by rejecting or minimizing the private and individual character of this same right, one inevitably runs into ‘collectivism’ or at least closely approaches its tenets,” Pope Pius XI, Quadragesimo Anno. Vatican translation. ¶46.

[2] St. Basil, “Letter 38” in Saint Basil: Letter. Volume 1 (1-185). Trans. Agnes Clare Way, CDP (New York: Fathers of the Church, 1951), 90

[3] Vladimir Solovyey, God, Man & The Church. The Spiritual Foundations Of Life. Trans. Donald Attwater (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 2016), xiv.

[4] Vladimir Solovyey, God, Man & The Church. The Spiritual Foundations Of Life, 54-5.

[5] Nikolaos Loudovikos, Church In the Making: An Apophatic Ecclesiology of Consubstantiality. Trans. Normal Russell (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2016), 45 [Quoting Maximos Mystagogy 665BC].

[6] St. Maximus the Confessor, “The Church’s Mystagogy” in Maximus the Confessor: Selected Writings. Trans. George C. Berthold (New York: Paulist Press, 1985), 188.

[7] Pope Benedict XVI, Deus caritas est. Vatican translation. ¶28.

[8] Pope Francis, Fratelli tutti. Vatican translation. ¶105.

[9] Vladimir Solovyey, God, Man & The Church. The Spiritual Foundations Of Life, 55.

[10] St. Albert the Great, On Resurrection. Trans. Irven M. Resnick and Franklin T. Harkins (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2020), 245.

[11] Vladimir Solovyey, God, Man & The Church. The Spiritual Foundations Of Life, 37.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.