Sin divides, and it does so in order to conquer and destroy. It often attaches itself to legitimate distinctions but turns them into fracture lines in order to break things up. Distinctions, of course, can be and often are good, because they prevent a monistic reduction of all things, but all distinctions must be held together by an overriding harmony which unites them together as one. This harmony is important, for it is what makes sure such distinctions do not end up being abused, and through such abuse, fracture what is meant to be whole. Once cut off from such a harmony, the various parts which used to make for a particular whole are not sustainable in and of themselves, and so they find themselves worse off than they were before. Plurality is important, but it must be a plurality which is supported by and promoted by an underlying unity which sees how the plurality works together as one. Plurality without unity absolutizes distinctions, pitting those distinctions against each other instead of having them work for and complement each other. Plurality which promotes unity allows us to enjoy the diversity and see the various ways the good can and does manifest itself through being. Distinctions are not bad in and of themselves, and they can be and are often formed in history for some good purpose. But when various distinctions are used to form barriers in society, when they are used, for example, to pit humans against each other instead of affirming their common nature together, such distinctions must be relativized. We must promote the greater good, the good of our nature, the good of humanity as a whole. Then sin, when it seeks to use such distinctions to destroy the common good, can be put in check, and we can begin to appreciate, once again, the plurality of the good itself.

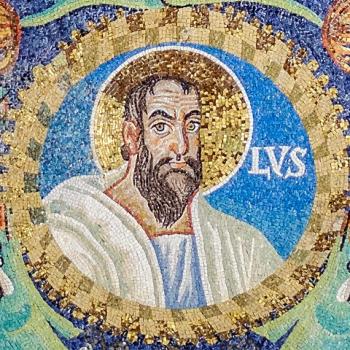

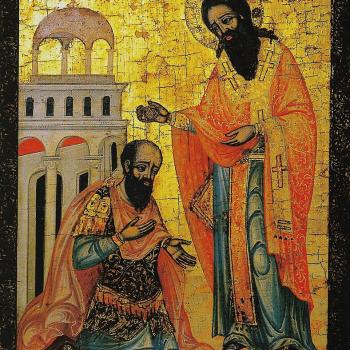

Paul understood this as he contemplated and appreciated the historical context which established the people of Israel, the relationship they had with God, and the special customs and laws which developed as a result of that relationship. He knew that there was a distinction between the people of Israel and the Gentiles, and he did not deny the value of that distinction. He saw the greatness of Israel and its customs. He also saw that this meant that the Gentiles also had their own customs and practices, many of which were of value and not to be rejected. The distinction between the two was not ignored by Paul, but he relativized it by reminding us the equality we have in our common human nature. Thus, when the distinction between Jew and Gentile was abused, such as when various Gentiles were told the only way to reconcile themselves with God was to embrace the customs of Israel, eliminating pluralism in the world, Paul would have none of it. Similarly, he would have none of it if the opposite took place, that is, if Gentile converts emphasized their traditions so as to undermine the customs and practices of Israel. He saw the distinction was valid, but the way it was being used to create discord was not. It was sin which lay behind that discord, sin which was trying to fracture and destroy the unity of humanity. He said the solution to the problem, indeed, of all the division which sin created in the world, is found in the work and accomplishment of Jesus Christ, for Jesus forms the bond which connects everyone and everything together, reestablishing the harmony which was lost due to sin:

Therefore remember that at one time you Gentiles in the flesh, called the uncircumcision by what is called the circumcision, which is made in the flesh by hands — remember that you were at that time separated from Christ, alienated from the commonwealth of Israel, and strangers to the covenants of promise, having no hope and without God in the world. But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ. For he is our peace, who has made us both one, and has broken down the dividing wall of hostility, by abolishing in his flesh the law of commandments and ordinances, that he might create in himself one new man in place of the two, so making peace, and might reconcile us both to God in one body through the cross, thereby bringing the hostility to an end (Ep. 4:11-16 RSV).

Christ overcomes sin. He brings back together what sin broke apart. The unity which he establishes does not deny the plurality of the good in the world, and the distinctions which could be made in regards that plurality. Rather, it gives the foundation by which that plurality is best established and preserved. Thus, Paul said that Gentiles did not have to follow the practices of the people of Israel. The people of Israel did not have to follow the practices of the Gentiles. Those traditions have value, and they can and should share the good they have with each other, not in a way which undermines the plurality, but rather, they should uphold each other the same way the persons of the Trinity uphold each other. Communion, therefore, is the answer, where persons remain, because relationships remain, but the divisions established by egos, divisions which try to establish individuals cut off from each other, are overcome. We must appreciate plurality and unity both.

The people of Israel had their laws, their customs, their expectations, some of which were universal, but much of which was for themselves alone. Those customs had value, and even if we are not expected to take them upon ourselves, that does not mean we should neglect or reject the value they had. They helped the people of Israel receive the grace they needed for their own special mission in the world. Salvation is from the Jews; in and through them, God would become one of us, embracing not just them, but the whole of humanity with such great love and mercy, God could and would bring together what sin had divided. The customs and traditions of the people of Israel helped them in their history, but they did more than that, because they also have spiritual meanings which go beyond their particular history, spiritual meanings which can and do apply to all. We do not have to deny their historical meaning in order to accept their spiritual meaning, nor do we have to deny the spiritual meaning in order to accept their historical meaning. Both have value, but for those who are not connected with the history of the people of Israel, that is, those who come from Gentile traditions, the spiritual meanings found in the customs of Israel continue to have meaning, as they point to and are fulfilled by Christ. This is why, even if we are not expected to follow them in their most literal fashion, nor in the cultural fashion which the people of Israel used to interpret them, we still have to appreciate the spirit behind them and engage it in our own context. In doing so, we will discover one of the many ways God works in and through plurality to bring us together as one. For just as the customs of the people of Israel have a spiritual meaning, so do the just and good customs of the Gentile traditions. That spiritual meaning is one in both of them, connecting them together. When we can discern it in one tradition, we should be able to discern it in the other, and in doing so, see how God was at work in and with the world, preparing it for the incarnation.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!