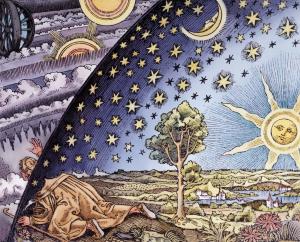

In Genesis, we read of the establishment of the firmament:

And God said, “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.” And God made the firmament and separated the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament. And it was so. And God called the firmament Heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, a second day (Gen. 1:6-8 RSV).

Most ancient readers of the text interpreted this to mean that the firmament existed as a translucent but solid barrier between us on the Earth and the heavens which exist beyond it. They used their limited (and often faulty) scientific understanding as a hermeneutic to the text, suggesting that science could explain features associated with the firmament, such as the way it was connected to water. Some thought the water solidified and became like ice, while others suggested that the waters became vaporous (due to the fact that they knew when water was heated, it would turn into a vapor and rise into the air). Nonetheless, they thought the supposed connection made between the firmament and water helped explain some natural phenomena (such as rain) as well as provide explanations as to the source for the water used in the flood of Noah (and perhaps where it returned, if it became vaporous). What is clear is that many, but not all, understood the text as literal history, and that literalism helped shape their cosmologies (though it was combined with what they learned from natural sciences, such as was found in the of Ptolemy).

There were some, while being in general agreement with their peers in regards cosmology, who looked at the creation story primarily as a theological story and not as a pure representation of history. They were much more flexible in their interpretation of the story. They understood the problem of an excessive, overly-literal interpretation of the text as they saw how it went against what could be known by the natural sciences (and, sometimes, seemingly contradicted itself). They thought readers should interpret the text in relation to what the science presented as true, and so they believed that the creation story should be read theologically, that is, typologically and allegorically. Thus, St. Gregory of Nyssa, going somewhat against the interpretation of his brother, St. Basil, wanted to understand what the firmament meant theologically. He saw it represented the barrier between sensible (material) and intellectual (spiritual) realities, with the firmament being at the “summit of sensible being”:

Rather, according to what Scripture says, the firmament is the summit of sensible being, around which the nature of fire revolves by the virtue of its power of perpetual motion, and is contrasted with the characteristics of the eternal, the incorporeal, and the intangible. For who does not know that everything firm is closely composed together, by virtue of something altogether hard and resistant in its nature? [1]

While Gregory gave a deeper reading to the text, it is clear that he still followed many of his predecessors in regards their general understanding of the text. He believed that the firmament possessed physical characteristics, though he put it at the height of material (physical) existence. This is because he saw it as being the point at which the physical realm came to an end as it touched the insensible or spiritual realm. This allowed it to be different from most physical objects as it touched and was influenced by the transcendent spiritual realm which lay beyond it. The firmament, thus, could be called heaven, but in calling it such, Gregory begins to shift the way it is understood, as he uses it to point beyond physical, material reality and to the immaterial realm, that is, “intellectual creation:

So, to reveal our thinking more clearly, we shall repeat the sense of what we have said in a concise form: the firmament, which is called heaven, is the boundary of the sensible creation. Beyond it comes the intellectual creation, in which there is neither form nor size nor spatial location nor measure of spacing nor color nor shape nor magnitude nor any of those things that can be observed below heaven. [2]

While Gregory followed a cosmology which is radically different from ours, he did offer us theological insights which we can use and adapt based upon our better scientific understanding of the universe. Instead of looking up into the sky and seeing a physical firmament, we can accept it as being the boundary between sensible and intellectual (or spiritual) forms or modes of being. The boundary exists, not just in the sky, but around all matter, as all matter is connected to and related to the spiritual realm of being (and can be said to “reside” in it). The boundary, therefore, relates to what we can sense, where most of us are incapable of sensing the spiritual real in which material being resides.

Science shows us that the notion that in the sky itself is some sort of hard, physical substance which we cannot go beyond, was erroneous, however, the metaphysical notion behind the creation story, the truth behind the myth, remains valid. There is a distinction between material and spiritual being. We must understand that this distinction is not absolute, but only relative, for in eternity, the two will be one and all that is physical will be spiritualized, thanks, of course, to the incarnation and the immanentization of the eschaton. While the full realization of the immanence of the eschaton will take place in eternity, due to the incarnation and the graces which it has given us, we can begin to experience that reality now. We can develop, as it were, spiritual senses which allow us to transcend the “firmament.” What was once impenetrable has become permeable due to the kenosis of the Logos.

There are many spiritual practices which we can follow that will help us experience the spiritual reality in which all physical being resides. In doing so, we will note that material being not only is in the spiritual real, but it is permeated by the spiritual realm, so that we should be able to encounter all things in and through their spiritualized (or transfigured) form. This will allow us to experience, at least in part, the glories of heaven. Many of these spiritual practices encourage us to distance ourselves from all our attachments to the world, attachments which keep us focused on the material form of being. Thus, St. Isaac the Syrian suggested, if we want to experience the purity and glory of intellectual reality, we must silence our thoughts: : “Whoever wishes to see the tranquil state of his intellect, let him keep himself from all thoughts, and the intellect will see itself with a quality almost like the sapphire transparency of heaven.” [3] If we do so, hopefully we will begin to see creation in a new way. That is, we should be able to see the goodness and beauty of all things, as we should see them in accordance to their essence, which is how God sees them and knows them as good: “But the eye of God does not have regard to creatures’ blooming beauty, nor does it define beauty and goodness in terms of a fine color or a fine shape, but rather in terms of how each thing, in its being, has in itself a complete and perfect nature.” [4]

However, sin has led us to lose our ability to appreciate and experience the way things are by nature. We have lost our ability to see the goodness in all things, to see the beauty which underlies creation. This will change through the grace of Christ, so that in and through him, the effects of sin will be overcome, and all things will reveal their glory. When we are united with that grace, when we are transformed and spiritualized by it, we shall be led to see how heaven itself permeates all things so that all things can be said to be heaven:

One day all will be heaven, and all things truth. Thus, what suddenly fell, has been revealed again in a long order ; and what the creature suddenly demolished, the Creator in a long succession of time is building up again; that he may restore all things in Jesus Christ. [5]

This should not be surprising. The fall has made the distinction between heaven and earth, so that in and through our experience of sin, we do not experience the kingdom of heaven in all things. But Jesus has penetrated and broken down that barrier. He offers his grace to all things so that all things can then be restored and truly be as they are by nature, that is, as they are seen and understood by God. And we, in our own restored state, will be able to experience all things in their glory, and so see the glory of God reflected in and through them. Of course, that goodness, even in temporal history, remains, as the essences of all things remain good. Thus, St. Augustine proclaimed that the “heaven of heavens,” the spiritual foundation or essence of all things, remains pure and undefiled despite the way sin has corrupted things in history:

Of course, the heaven of heaven which Thou madest in the beginning is some intellectual creature, which, though in no way co-eternal with Thee, the Trinity, is nonetheless a participant in Thy eternity. By virtue of the sweetness of the most happy contemplation of Thee, it restrains its own mutability; and, without falling once since first it was made, it transcends every variable vicissitude of time by adhering closely to Thee.’[6]

The cosmic fall, experienced in history, allow individual things to become less than their essential nature. That is, the nature of all things remained good and pure, but the way those natures are participated in historical existence means particular subjects establish themselves in history less than what they can and should be by nature. Thanks to the incarnation, and the graces which it has brought to creation, everything is able to find its way back to its proper nature, to attain the purity which it lost, and reveal the innate beauty and goodness which has been given to them by God. Thus, the corruption of sin is reversed by the incarnation. All those who join themselves to Christ can be spiritualized; if they do not turn away and put up new barriers between them and grace, they will be able to realize not only the original greatness of their own nature, but they will also find themselves rising up beyond it, as they will participate in the divine life itself through their union with Christ. This, however, is what God originally intended; the goodness in which all things were made included the ability to be raised up by grace, so that they can transcend themselves and receive, through such transcendence, the great bounties of God. That is, all things were made good, and creaturely subjects were given the freedom to become less than or greater than they were by nature; those which make themselves less than they should are said to sin, while those who open themselves up to grace become deified and are said to be partakers of the divine nature itself.

We must, therefore, embrace the purity of our nature. When we engage it, we will find its inclinations are good and we can follow them where they shall lead, for they will encourage us to transcend ourselves and take in more and more of God’s deifying grace. The more we do so, the more we will experience the eschaton, the kingdom of God, for ourselves; the firmament, the point which lies between physical and spiritual forms of reality, will be transcended in this fashion, showing us its own nature is relative and not absolute.

Insofar as we find ourselves experiencing the glory of the kingdom of God, we can be said to reign with Christ, but insofar as we find ourselves still unbalanced, attached to the physical mode of being without holistically being attuned to the spiritual reality from which it emerges, we are still on a pilgrimage, a pilgrimage to the kingdom of God. Of course the pilgrimage must be seen as an interior journey, where we become more and more aware of ourselves, that is, coming to know who and what we are by nature. As it is an interior pilgrimage, it is about uncovering or revealing the kingdom of God which is already within us. The more we journey upon the path, the more we make the inward journey and perceive spiritual realities which we had previously not been able to sense, that is, the better we will be able to experience the kingdom of God. Of course, we must remember, while we take this journey, we must not neglect our material being, and the physical world around us. Our fullness is found in the union of spirit and matter. Jesus, after all, did not ignore the world and its needs, but rather, he offered it his graces, giving out graces which not only heal people spiritually, but physically as well. We must follow after him. We must go on the inward journey, to discover the kingdom of God within, but we must do so in a way which we continue to recognize our nature is at once spiritual and physical. We cannot ignore the physical world and what happens around us and think ourselves as faithful followers of Christ. For indeed, the immanence of the eschaton must remind us not to seek some gnostic separation of spirit from matter. Thus, we can say that the firmament represents not an absolute division between spiritual and physical forms of being, bur rather, the bridge which connects the two, the bridge which shows the two form one interdependent whole instead of two absolutely distinct forms of being.

[1] St. Gregory of Nyssa, On the Six Days of Creation. Trans. Robin Orton (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2021), 65-6.

[2] St. Gregory of Nyssa, On the Six Days of Creation, 68.

[3] “Selection from the Holy Fathers on Prayer and Attention“ in The Philokalia. Volume 5. Trans. Anna Skoubourdis (No location, Australia: Virgin Mary of Australia and Oceania, 2020), 207 [ possibly by St. Kallistos Angelikoudes].

[4] St. Gregory of Nyssa, On the Six Days of Creation, 80.

[5] John Colet, “Celestial Hierarchy” in Two Treatises on the Hierarchies of Dionysius. Trans. Joseph Hirst Lupton (London: Chiswick Press, 1869), 104.

[6] St. Augustine, Confessions. Trans. Vernon J. Bourke (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1953; repr. 1966), 374-5.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!