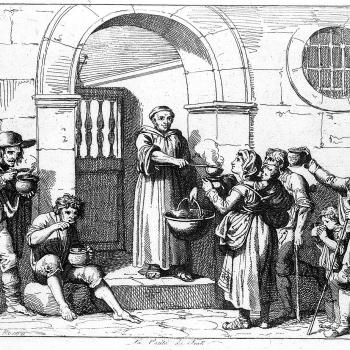

When we see people in need, and we have the means to help them, we should do so. “But if any one has the world’s goods and sees his brother in need, yet closes his heart against him, how does God’s love abide in him? Little children, let us not love in word or speech but in deed and in truth” (1 Jn. 3:17-18 RSV). When we fail to do so, we sin through a sin of omission, because we have failed to do what we ought to do. This is especially clear when we see those in need; we cannot say we did not know they were suffering, nor that they needed someone to help them. And since Jesus taught his followers that they are to take care of the needs of their neighbor, Christians cannot say they didn’t know they had a duty to do anything and act as if their sin is negligible because of ignorance. We might not know all that we can do, nor the best way to help our neighbor, but we know we are to do our best to help them, and if we can’t do it ourselves, find someone who can. When don’t do so, our we are culpable for our sins of omission.

Sadly, most of us only consider and ponder sins of commission, thinking they are the only ones which count. But Scripture warns us otherwise. When we know we should do something and we do not, we sin. “Whoever knows what is right to do and fails to do it, for him it is sin” (Jas. 4:17 RSV). The consequences of not doing what we should do can be great, though of course, there will be degrees of culpability based upon what we know and what we can do. This is not to say ignorance of what is right will alleviate our obligation, just as ignorance of the law will not mean the law cannot and will not punish us. However, it can affect the degree of culpability. Likewise, we must understand not all ignorance is the same. Is it, for example, willful ignorance? If so, then we not only find our ignorance does not undermine our responsibility, but rather, our sin will be greater, as we will have knowingly prevented ourselves from doing what we could and should have done. Indeed, by actively avoiding our responsibility, by trying to remain ignorant of what we could and should do when we encounter a problem, we show that we are not truly ignorant and are merely compounding our culpability for our omission. If, on the other hand, we truly were not aware of the problem, and so we truly acted out of ignorance and there was no way we could have acted otherwise, the culpability will be greatly lessened (and perhaps, rendered nil). What is important for us to keep in mind is that as soon as we are made aware of an issue, we can no longer claim ignorance of the problem; we must then either engage it, the best we can, or we commit a sin of omission.

Truly, the way many of us act in regards the environment, and the environmental crisis which lies before us, shows us that we, as a society, are guilty of a major sin of omission. We know the problem exists. There is too much data for us to ignore the problem. We even have a sense of things we can do (even if we do not know all that we can and should do). We know how greatly we have polluted the world and that we can do much to rectify that. We, however, find ourselves unwilling to do so; it is a major undertaking which must be done, and while it also a costly one, it will end up much more costly if we do not do so. For the future of the world, including the future of humanity, is at stake; whether or not humanity (and many other forms of life) are threatened with extinction or not, those who survive in the midst of the climate crisis created by our poor stewardship of the earth will find their quality of life greatly diminished, even as it will lead to mass hardships and death for those who live in the conditions which we have created for them.

The Earth is our home. We are called to take care of it. We are obligated to protect it from all that would harm it, including and especially ourselves. We are meant to guard it so as to make sure future generations receive the same blessings from it which we have. God gave us stewardship over the Earth, but God has also warned us what happens if we prove to be bad stewards (cf. Matt. 21:33-46; Matt. 25:14–30; Lk. 16:1-13). We will find many of the graces we have been given will be taken from us so that we will have to face the consequences of our actions without them. When we see environmental disasters before us, we have no excuses. We can’t claim ignorance. We might not understand all the ramifications of what we have done, but we can see our indifference has led to destruction, and that destruction will continue to become worse and worse as we fail to act. And, it really does not take much for us to study and learn about climate change and the science behind it, so that it becomes willful ignorance when we deny what is expected of us to rectify the problems of climate change. Such willful ignorance shows us the depths of our depravity, the depths of our sins of omission.

Pope Francis, Patriarch Bartholomew, and the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury, John Welby, all understand the crisis which lies before us, and they routinely speak on the need for Christians, and for humanity as a whole, to come together and act before the environmental problem becomes completely unmanageable. We risk losing everything, including our very existence, thanks to our sins, both those which we actively committed, but also those related to sins of omission. We have failed to rectify the harm which we have done to the world, letting things become much worse as a result. Thus, in a combined statement, releases on September 1, 2021, they said:

The current climate crisis speaks volumes about who we are and how we view and treat God’s creation. We stand before a harsh justice: biodiversity loss, environmental degradation and climate change are the inevitable consequences of our actions, since we have greedily consumed more of the earth’s resources than the planet can endure. But we also face a profound injustice: the people bearing the most catastrophic consequences of these abuses are the poorest on the planet and have been the least responsible for causing them. We serve a God of justice, who delights in creation and creates every person in God’s image, but also hears the cry of people who are poor. Accordingly, there is an innate call within us to respond with anguish when we see such devastating injustice. [1]

Not only does our indifference threaten humanity as a whole, even if it does not end up producing an extinction event, it will still create more unjust suffering and death for those who are most vulnerable. Christians should know that they are obligated to take care of their neighbor, of those in need, so that they will find themselves that much more culpable for their sins. For God, having taught them, and given them grace, expects more out of them than those who are not so directly influenced by grace.

Having come to realize the problem which lies before us, we should see that we have an opportunity to do what we have failed to do in the past, to make things right, and in doing so, making the world a better place:

We are in a unique position either to address them with shortsightedness and profiteering or seize this as an opportunity for conversion and transformation. If we think of humanity as a family and work together towards a future based on the common good, we could find ourselves living in a very different world. Together we can share a vision for life where everyone flourishes. Together we can choose to act with love, justice and mercy. Together we can walk towards a fairer and fulfilling society with those who are most vulnerable at the centre. [2]

And, those in positions of authority and power, those with all the wealth, are expressly obligated to use what they have for the common good:

To those with more far-reaching responsibilities—heading administrations, running companies, employing people or investing funds—we say: choose people-centred profits; make short-term sacrifices to safeguard all our futures; become leaders in the transition to just and sustainable economies. ‘To whom much is given, much is required.’ (Lk 12:48) [3]

If we are not in such positions of power or authority, we still have the obligation to lift up our voices, to come and work together to change the system and make sure those who have the power and authority to do things will change their behavior. That is, we need to make sure that they do not continue being a part of the problem. They need to become a part of the solution. Likewise, we must look at the little things which we can do, and do them as well, knowing that if the majority of the world acted differently and did not abuse the world as much as they have in the past, we will begin to see changes and things will be made better. It is important we do our part, but it is also important we realize who has more responsibility and make sure those who have it do not fail to do what they ought to do, less we all suffer the consequences of their sins of omission. Which is why the Pope, the Patriarch, and the Archbishop of Canterbury said it is now time for us all to repent and change our ways:

Nature is resilient, yet delicate. We are already witnessing the consequences of our refusal to protect and preserve it (Gn 2.15). Now, in this moment, we have an opportunity to repent, to turn around in resolve, to head in the opposite direction. We must pursue generosity and fairness in the ways that we live, work and use money, instead of selfish gain.[4]

Christians, of course, are not the only ones who know this. The problem is a problem for the whole world. The problem is for everyone. The future of humanity is at stake. What we do, or do not do, will determine the conditions in which future human generations will be born. The fact that so many do not care about what happens to their neighbor, as they live before them, explains why so many do not care what happens to future generations; selfishness has led to indifference. But we should care, if for no other reason than for that very same selfishness, for we should realize that we, not just those living in the future, will experience the problems of climate change. We are already doing so. Even if we are rich and powerful, the environment is more powerful. It will create terrible weather patterns which will affect everyone. We won’t be able to buy our way out of it, but we can work together and fix the damage we have committed. We must do so. We have long ignored our responsibility. Our sins, especially our sins of omission, cry out to God. Woe to us if we do not repent before it is too late.

[1] Pope Francis, Patriarch Bartholomew, and Archbishop Justin Welby, “Joint Message For the Protection of the Environment” (9-1-2021).

[2] Pope Francis, Patriarch Bartholomew, and Archbishop Justin Welby, “Joint Message For the Protection of the Environment” (9-1-2021).

[3] Pope Francis, Patriarch Bartholomew, and Archbishop Justin Welby, “Joint Message For the Protection of the Environment” (9-1-2021).

[4] Pope Francis, Patriarch Bartholomew, and Archbishop Justin Welby, “Joint Message For the Protection of the Environment” (9-1-2021).

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!