In God’s engagement with history, God is revealed as a Trinity. This revelation, the way the Trinitarian God is revealed to us, is called the economic Trinity, coming from the Greek word, οἰκονομία, oikonomia.[1] Each Trinitarian person interacts with us, and in that interaction, reveals themselves to us in accordance to that interaction. We learn of their existence, as well as their relations to each other, through their revelatory activity. Each such action differs in what it reveals, but each, in turn, reveals the reality of the Trinity. A prime example of such an economic revelation of the Trinity is found in the baptism of Christ:[2]

And when Jesus was baptized, he went up immediately from the water, and behold, the heavens were opened and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove, and alighting on him; and lo, a voice from heaven, saying, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased” (Matt. 3:16-17 RSV).

Here we have the Son being confirmed as truly the Son of the Father. Side by side with the declaration made by the Father we have the Holy Spirit revealing itself, “descending like a dove.”[3]From what we read concerning the baptism of Christ, we do not learn much about the Trinitarian persons, but what we learn is enough. We are shown that there is some sort of relationship analogous to a Father-Son relationship between the Father and the Son. Likewise, we are shown that the Holy Spirit somehow is connected with and reveals itself in relation to the Father and the Son.

Thus, through the economic Trinity, that is, in the way God is revealed to us in the economy of salvation, we are shown various truths about the Trinity, truths which we can and should believe because the Trinity reveals them to us. Nonetheless, we must not misconstrue it as being all that is possible to be revealed, that is, it suffices in presenting to us the Trinity but it does not exhaust the reality of the Trinity. What lies behind the economic Trinity is said to be the immanent Trinity, the Trinity as it is, not just in revelation, but as it is for the Trinitarian persons for themselves, how and what they know of themselves and to each other. This knowledge transcends human comprehension, which means, the immanent Trinity is a mystery.

Thus, the Trinity is revealed to us in and through the economic Trinity; what we know about the Trinity we know through revelation and what we can apprehend through such revelation. It must not be confused as representing the fullness of the divine nature, nor should we assume, through the way we apprehend the persons through the economic Trinity, we comprehend those relations. We do not. God transcends us. The divine persons transcend us. Their relations transcend us. We can and will talk about them in relation to what has been revealed, but we must understand the limitations of such talk.

Karl Rahner in his important work, The Trinity, reminds us that even though the immanent Trinity transcends us and is incomprehensible to us, it is nonetheless the same Trinity which is revealed to us in the economia of salvation. The persons, as they reveal themselves to us, are not other than the persons of the immanent Trinity:

The basic thesis which establishes this connection between the treatises and presents the Trinity as a mystery of salvation (in its reality and not merely as a doctrine) might be formulated as follows: The “economic” Trinity is the “immanent” Trinity and the “immanent” Trinity is the “economic” Trinity. [4]

We can believe what is revealed to us in the economia of salvation because we can trust God and what God reveals to us as being true. But we must remember, it is presented in the best, most fitting way, that is, in a way points to and suggests a greater truth than what is revealed. That is, we are given a form of the truth which we can apprehend, but we must remember, the fullness of the truth lies beyond our apprehension. Thus, as Pseudo-Dionysius expressed in his works, the incomprehensible nature of God makes it so that we should be cautious in making any designation concerning God, for God is beyond all such designations, and yet we can use and employ what God has revealed to us to talk about God, knowing they serve as the best way to have us think about God.

Revelation is skillfully presented to us so as to make sure we will not go far astray if we properly engage it and discern what it implies. But, we must be cautious and not try to seize upon revelation and absolutize the form which we have received. The economic Trinity must not be confused for the absolute transcendent nature of the immanent Trinity. The economic Trinity is the immanent Trinity, and the immanent Trinity is the economic Trinity, because the persons are the same, but there is a distinction between two, in that the economic Trinity is only a representational form of what is contained in the immanent Trinity. When we forget this, when we think we can comprehend God because of how we apprehend the economic Trinity, we lose sight of the Trinity itself and so end up abusing revelation.

The economic Trinity is the immanent Trinity, because the persons presented in the economic Trinity are the same persons as the persons of the immanent Trinity. What is revealed of the relations between the Trinitarian persons point to the transcendent reality of those persons in the immanent Trinity. Nonetheless, we must also say that the immanent Trinity is the economic Trinity because the persons of the immanent Trinity (designated as Father, Son and Holy Spirit) skillfully present themselves to us in such a way that we can best understand them and their relations with each other. How they act and interact in the economy of salvation tells us something about them in relation to the immanent Trinity. They would not act in such a way to have us confuse the persons and their relations by acting in ways which are contrary to their interactions with each other in the immanent Trinity.

We are given revelation so we can apprehend God; if revelation were misleading, it would defeat the purpose of revelation. This is why, when discussing the Trinity, and the theological implications of the Trinity, we must rely upon what is revealed to us in the economy of salvation if we want to apprehend the truth. The economic actions of the persons, that is, of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, therefore, is connected to the immanent Trinity, revealing in their economic interactions how they interact with each other in the immanent Trinity.

One of the greatest difficulties we have when engaging the immanent Trinity (and therefore the Trinity) is the fact that God is eternal. The actions and relations of the Trinity are eternal, but they are revealed to us in ways which we understand temporally. The Son is “begotten” of the Father. We want to interpret this temporally. We want to think as if there were a before” and “after,” to the begetting of the Son, but in reality, the begetting of the Son is not a temporal event; it is an eternal action of the Father, so that the relation between the Father and the Son is contained in the fact the Son is begotten of the Father eternally. Likewise, the Holy Spirit, which is not begotten, is said to proceed in eternity, a procession which likewise has no beginning nor an end, as it is eternal, and yet that procession comes from the Father and the Son. This relation is revealed to us in the way the Father and the Son are both said to send the Spirit to us (cf. Jn. 14:26; Jn. 15:26; 1 Jn. 4:13). The Spirit is not sent multiple times, but rather, it is sent once. It is sent from the Father and is sent by the Son at the same time, with the Father nonetheless being said to be the one who initiated the sending of the Spirit. This points to us that the procession of the Spirit in the immanent Trinity, whereupon we learn that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and yet also is said to proceed from the Son. Just as the Father and Son do not send out the Spirit in two different sending, so the spiration of the Spirit from the Father is not a separate procession from the spiration of the Spirit from the Son. The procession of the Spirit is eternal, even as the begetting of the Son is eternal. The begetting of the Son and the procession of the Spirit must be seen as concurrent with each other, not separate from each other. There might be a logical priority, but there is no temporal priority. In the generation of the Son, we find the procession of the Spirit from the Father and the Son. This means that the Father is, in a way, the source and foundation of the Trinity, the “uncaused cause,” the one without a personal origin, while the Son and Spirit rely upon the Father for their foundation, confirming the “monarchy” of the Father.

If we cannot engage the immanent Trinity through the way the Trinity reveals itself to us in the economy of salvation, then revelation itself is useless. It is not trustworthy. This is why we must accept that the economic Trinity truly presents to us the immanent Trinity in a form which we can apprehend. Nonetheless, we must also accept that the form of the truth of the Trinity which we apprehend is less than the fullness of the immanent Trinity. The two are related, but not identical; Rahner, in his equation, is clear that the logical distinction between the two remains, but that distinction must not be used to divide them and make revelation useless. When we believe what is revealed in the economic Trinity, we believe in the Trinity, and nothing else but in the Trinity.

[1] Oikonomia means the “management” or “handling” of the household, and when used in relation to revelation, it is the way God manages or handles creation (the house which God manages). When talking about the economic Trinity, then, we are concerned with the way God works with creation.

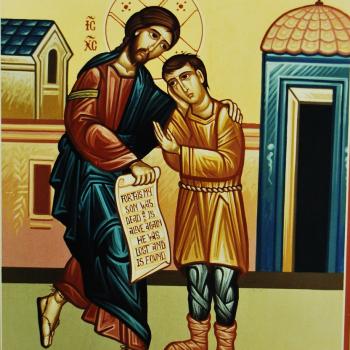

[2] There are certainly other events in which and through which the Trinity reveals itself. A prime example is found when Abraham encountered God at Mamre. While there is a debate as to whether or not the three person Abraham encountered were the persons of the Trinity, or angels who represented the persons, in either reading of the text, Abraham is able to discern something about the nature of God which likewise can be and is applied to theological discourses on the Trinity

[3] This shows us that the economic revelation of the Trinity often comes to us in and through images and symbols. The Holy Spirit is not a dove, but it uses a dove to represent itself.

[4] Karl Rahner, The Trinity. Trans. Joseph Donceel (New York: Crossroad Herder: 1998), 21-2.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!