Sergius Bulgakov, for a period of his life, considered himself to be a Marxist, but that changed when, in the middle of his graduate studies in economics, he saw how Marxist analysis failed to take into consideration developments of science and technology after Marx. It can be said that science helped direct him to the Christian faith. This is not to say, once he became a Christian, Bulgakov rejected the social concerns which led him to embrace Marx. Rather, he felt that Marxism, like many ideologies of its time, failed because it was a closed system which could not truly adapt to what scientific explorations after Marx had discovered.

In his transition from Marxist to Christian, Bulgakov embraced a highly developed theological tradition, known as Sophiology, which he would develop in his own writings. Even as he continued to write on economic matters, from a philosophical standpoint, he used what he found in Sophiology as a way to engage what he wanted to say and teach. Thus, when he wrote on economics, he did so as a Sophiologist. He was clear, as an economist, that economics needed a philosophical background behind it, which could and would unite science with morality. Those who follow after Wisdom will engage all that can be discerned from multiple disciplines and unite them together. Thus, he writes:

Science is sophic: this is the answer we can give to skeptical pragmaticism and dogmatic positivism. It is removed from Truth, for it is a child of this world, which exists in a state of untruth, but it is also a child of Sophia, the organizing force that leads this world to Truth, and it therefore bears the mark of truthfulness. Truth as a process, as becoming. [1]

He understood that science itself does not seek for or establish the Truth as much as it is a process by which humanity comes to know the truth. To engage science is to recognize its potential as well as its limitation. The sciences reflect their maker, humanity; indeed, they come out of humanity, representing a quality of the human condition:

Science is an attribute of man, his tool, which he creates for one or another task. Science is thoroughly anthropological and, insofar as actuality and economy in labor is the essential nerve of human history, science is also economic, or pragmatic. In understand science we must understand man. It is not science that explains man but man who explains science. [2]

However, because of the relationship between humanity and the unitive principle behind creation, Sophia, science demonstrates not just the humanity which established it, but Sophia as well. As Sophia works to unite humanity as one, as Sophia works to unite creation as one, so the sciences try to create an exhaustive, and comprehensive, understanding of the cosmos and all that is within it:

In terms of content, the truthfulness of science is based on its sophic nature; Sophia’s organizing power makes it possible. In it Sophia comes to possess the world. We might say that the awakening of the world’s self-consciousness finds expression in science, as the world’s deathlike stillness falls away. So real progress does occur as science develops. [3]

Science, because it provides us a process which leads us to greater and greater knowledge and understanding, continuously offers ways to transcend itself, allowing therefore a true sense of progression. Through science, what one day seems impossible might and often becomes possible on another day. But the potential for such transcendence is what led Bulgakov to see that there has to be a focal point for that transcendence, something in which all the knowledge and wisdom comes from, and that focal point is Sophia. Obviously, Sophia is more than this, but by seeing the connection between Sophia and the sciences, Bulgakov made it clear that Christianity should embrace the sciences and not dismiss them as being contrary to the Christian faith. Technological advances, therefore, present a way for humanity to realize its potential as it grapples with the universe at large and finds the way to make nature help humanity and its goals:

How is technology possible? How can we characterize the technical relation of the subject to the object, of man to nature? The possibility of technology, apparently, presupposes the accessibility in principle of nature to human action, its receptivity to human aims. As a consequence of the general connectedness of nature, the unity of the cosmos, we must speak of the accessibility or obedience of nature generally to man. Although man remains immeasurably far from possession of nature, this path is open to him.[4]

What comes out of science and technology is Sophic in nature. Humanity is Sophic in nature. Thus, to engage the science is a way in which humanity properly acts on its own nature. The Divinity, likewise, is Sophic in nature. This is what allows for a connection between God and humanity, for God is Divine Sophia, while humanity represents a created manifestation of Sophia. To embrace the Sophiological character of humanity, then, humanity must act out its Sophic core, to creatively engage the universe and be sub-creators in the world. What comes out of science and technology cannot be said to be unnatural because all science and technology does is work with what is possible with nature, using the creative Sophic core in humanity to produce what is beneficial to humanity. Science, and what it offers, is a positive gain to humanity and helps humanity truly live: “Science is a tool for reviving the world, for the victory and self-affirmation of life. “[5]

This is not to say what is produced by science cannot be manipulated and abused. Such abuse, like all evil, comes not from itself, but from a distorted use of its potential. To properly embrace science requires humanity to engage Sophia, wisdom, through correct moral activity. Thus, the problem is not science, nor technology, but the lack of a holistic embrace with other elements of our Sophic nature which can turn technology astray. Or, as Paul Evdokimov explained:

Technology imposes its rhythms and its speed but morally it is neutral. It is only an instrument in our hands. Technology’s capacities of power grow faster than the mind of the technician, like the apprentice-sorcerer, the consequences going beyond our use and control. Science exerts an effective control on our biological constitution, modifying time and cosmic conditions, reaching outer space and making the universe intelligible. We must become conscious of the extent of this new power when it acts upon our political systems and leads to unintended consequences. In the face of the dynamic automation of technology God calls upon us to master it, for it too is a gift of God and we are responsible for it. We must be the masters of ethical options in our social context. [6]

We cannot and must not reject the invaluable tool of science, especially when it is being used to help save lives (such as when it is used to create vaccines which protects us from disease). It would a morally reprehensible act to reject the good which science can provide. It is as much an abuse of science to ignore its proper application as it works for the common good even as it would be an abuse of science to use what is learned for some nihilistic end. Science teaches us what is possible, and knowing what is possible, we engage it with our Sophic potential to discern the best ways to deal with the problems at hand. As sciences develop, the potential solutions develop, and so the best ways to deal with the problems we face will change. Morally we do what we can for the common good when difficulties arise, even if it means we find ourselves inconvenienced. If we do not, then our unwisdom will lead to chaos in the world as the problems which we ignore become exponentially worse. For example, allowing the spread of a deadly, highly contagious disease in the world, when it is possible to properly contain it, represents an anti-Sophiological approach to the world, And, it should not be surprising, then, that the result will be similar to the harm demonstrated in the story of the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” for chaos spreads when human ignorance and negligence is promoted over the common good.

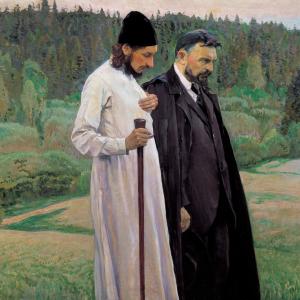

The priest-martyr-scientist (and saint) Pavel Florensky followed the Sophic embrace of all the elements of the human person, using them to work together to serve the common good. Life is good. Thus, he understood that what is alive is creative and will act in the world according to such creativity. Science is one of the many ways in which this good is to be achieved. To reject science, to strangle its development, is antihuman and anti-Sophiological. This is not to say there were not problems in the various scientific fields. Since they come out of humanity, they reflect the problems found in humanity. Perhaps there is no greater representation of this than the fragmentation of the sciences into completely independent disciplines (a common feature of his time). But he also believed that the sciences were coming together, presenting a universal, holistic picture:

But a strange phenomenon soon made itself known: the domains of the various sciences began to merge. Many new objects and groups of phenomena appeared whose study required more than one scientific discipline. For example, the problem of creativity – in literature, painting and sculpture, music, and so on. Biology began to merge with technology.[7]

The sciences, and what they offer, should never be rejected. They are to be embraced as a part of the process by which humanity brings together the world at large. They help serve humanity as it finds joy and beauty in the world at large, even as they are one of the many tools which humanity has on hand to help fulfill its mission in the world. And, as Evdokimov realized, many of the other elements of the human person had been developed in other eras far advance of the sciences, so it is not surprising that the sciences have taken center stage in discerning the world at large:

Present-day science is no longer a dream. As a dream, it has been magnificently realized, and beyond all expectations. Its rapid progression is becoming unpredictable. It is going beyond the laboratories of scientists, and it is indispensable in any meditation on being, the existence of man and his destiny. It is neither theology nor philosophy that is changing the face of the world. It is science. Cybernetics and automation are providing the human brain with a marvelous complement. They allow very exact forecasts to be made which concern us all. Power over biological processes and over space, plant in human consciousnesses the seeds of a new spirit of prophecy. By an effective solidarity, all men find that they have a common destiny with its own risks. [8]

We should not ignore our need to develop other reflections of Sophia contained within humanity. We must not limit our explorations to what we can discern from the sciences. Nonetheless, we should also recognize advances in the sciences can and should help us advance in those other explorations. We must not avoid the sciences, we must not deny their value in helping humanity achieve its potential, including and especially in helping humanity live in ways which previous generations could never believe possible. But we must always remember the advances of the sciences must follow humanity and its particular needs:

Science is an answer to a question that precedes science. Practical motives or life interests, imperiously resting their attention on a given aspect of life, call into being a corresponding science. The history of science is not the history of the coherent, logical development of science, as it would emerge from purely theoretical relations; rather, life impulses and practical needs have called different branches of knowledge into being in different periods. [9]

Sophiology promotes the proper use and application of the sciences. It does not fear what the sciences can learn. It does not deny the advances created by technology, suggesting such advances as being unnatural. How could it, because those advances clearly follow nature itself? It certainly does not want us to confine ourselves to one area, to one domain, of existence. Thus, knowing the limitations of the sciences, we certainly will not limit ourselves to what they can reveal. But, following what Sophiology teaches us, we will accept, with gratitude, what the sciences learns which can benefit humanity, especially when it saves human lives. For, that is truly the wise thing to do.

[1] Sergei Bulgakov, Philosophy of Economy. The World as Household. Trans. Catherine Evtuhov (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 176.

[2] Sergei Bulgakov, Philosophy of Economy. The World as Household, 172-3.

[3] Sergei Bulgakov, Philosophy of Economy. The World as Household, 176.

[4] Sergei Bulgakov, Philosophy of Economy. The World as Household., 120.

[5] Sergei Bulgakov, Philosophy of Economy. The World as Household, 177.

[6] Paul Evdokimov, “The Church and Society” in In the World, Of the Church: A Paul Evdokimov Reader. Trans. Michael Plekon and Alexis Vinogradov (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2001), 77.

[7] Pavel Florensky, At the Crossroads of Science & Mysticism. Trans. Boris Jakim (Kettering, OH: Semantron Press, 2014), -19 [ Lecture Three]

[8] Paul Evdokimov, Ages of the Spiritual Life. Trans. Sister Gertrude, S.P. Revised Michael Plekon and Alexis Vinogradov (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2002), 109.

[9] Sergei Bulgakov, Philosophy of Economy. The World as Household, 170.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!