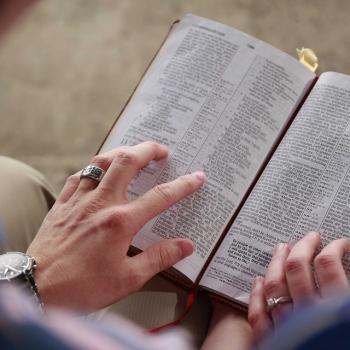

Sacred Scripture is made up of those texts which hold a central place in representing the Christian faith. “Sacred Scriptures are those which were produced by men who cultivated the catholic faith and which the authority of the universal church has taken over to be included among the Sacred Books and preserved to be read for the strengthening of that same faith.”[1]

The various books which make up the canon of Scripture take on a greater meaning when they are read together than when they are read apart. The whole is greater than the sum of the parts. The particular intentions of the various authors are transcended by the meaning the church receives from the texts. For the texts come out of inspirations of the Spirit which the church receives and uses to grow in its own understanding of the faith. This means, of course, the church can and does develop meanings to the texts which the original authors did not know or intend, even as it develops its own doctrinal positions. As Nicholas of Cusa explains, the Holy Spirit directs this development, and so we must take care to listen to and heed the words of the church today because what the church teaches today is relevant to our own particular context:

Hence, even if today there is an interpretation by the Church of the same Gospel command differing from that of former times, nevertheless, the understanding now currently in use for the rule of the Church was inspired as befitting the times and should be accepted as the way of salvation. [2]

Scripture does not possess only one true interpretation. Rather, thanks to the transcendent Spirit which inspired the writers, Scripture is a capable of many readings, many interpretations, which flow from that original inspiration. The authors of the texts know what they wanted to write and convey, and the Spirit allowed them to do so in such a way that their intended meaning is true while allowing a variety of other meanings to the text which the authors themselves did not know or understand.[3] Now, this is not to say every meaning someone wants to get out of Scripture is true, because, obviously, there are objective elements to the truth. Nor does it mean, if we talk about some sort of truth, through the guise of Scripture, our hermeneutic scheme is good and what we discuss properly flows from Scripture. It might not. But so long as what is suggested is true, St. Augustine thinks we do not have to worry if Scripture is being interpreted poorly[4]:

Now, having heard and considered all of these, I do not wish to quarrel over words; ‘for that is useless, leading only to the ruin of listeners.’ But, the Law is good for edification, if a man uses it rightly, because its purpose is charity, from a pure heart and a good conscience and faith unfeigned. Our Teacher knows on what two precepts He hung the whole Law and the Prophets. Now, if I ardently profess these, O my God, ‘Light of my eyes’ in secret, what harm does it do me, if different meanings can be understood in these words, meaning which yet are true? What harm, I say, does it do me, if I hold about the writer’s intention an interpretation different from another’s? Of course, all of us who ready try to find out and understand what he whom we are reading intended, and, when we believe him to be veracious, we would not dare to think that he has said what we either know or think false. Therefore, while every person strives to perceive the meaning in holy Scriptures which the writer put there, how is it wrong if one perceives the meaning which Thou, O Light of all truthful minds, dost show to be true – even though the author of whom he reads does not grasp the same meaning, yet is perceiving a true meaning, but not this one?[5]

Augustine suggests that it can be dangerous to needlessly quarrel about the meaning of Scripture so long as the meaning which we get from our reading represents the truth in some fashion or another. This is what Scripture is for: to point us towards the truth. And, to be sure, there are many ways Scripture does this, as it provides us many ways of learning various truths. For, as Augustine suggests, Scripture is like a spring:

Just as a spring, within its small space, supplies a more abundant flow over wider areas by virtue of the many streams which feed it than do any one of those streams which lead away from this spring through many regions, so, too, does the story told by the original dispenser of Thine, which was to supply many who would speak of it in the future, cause to bubble forth, by the tiny flow of Thy word, floods of clear truth, from which each man may draw the truth that he is able to get concerning these things – one man one truth, another man another – through the longer windings of their discussions.[6]

This does not mean we should remain unconcerned with the way people interpret the text: without proper training, without proper guidance into particular universally established interpretations based upon good hermeneutic principles, we can easily be led astray and abuse Scripture. That fault, as St. Hilary suggests, is from us and our minds. Heresies are created when proper hermeneutical principles are rejected and various imbalanced notions come out of our reading of Scripture and tradition:

Many have appeared who understood the simplicity of the heavenly words in an arbitrary manner and not according to the evident meaning of the truth itself, interpreting them in a sense which force of the words do not warrant. Heresy does not come from Scripture, but from the understanding of it; the fault is in the mind, not in the words. [7]

Biblical studies are important. They can help us understand, to some extent, what the authors intended us to learn. In engaging such a practice, we must acknowledge limitations and realize all attempts to get to the original authorial intent are mere reconstructions. The better the principles behind the reconstruction, the closer we will get to that original intent and hopefully learn about the truth which lay behind that intent. But even if we cannot do that, we can still engage Scripture in a variety of ways, imbibe in the Spirit which inspired it, and be spiritually enriched. Again, we must recognize that we are not confined to the original authorial intent.[8] We should respect it and find the meaning which can be had by it while we remain open to the greater, developing understanding which can be had from Scripture as we come to it in our own particular context. The church suggests there are various ways to engage Scripture, the various “senses” of Scripture (literal, allegorical, moral, and anagogical), and each of these can be seen as a hermeneutical lens which we use to keep Scripture relevant without dismissing its original meaning and value. Thus, as we must not dismiss the meaning implied by the original intent of its authors, we must not dismiss the further meaning which can be had as Scripture is interpreted in a new light, in a next context, so long as they are seen as complementary to each other (each, thereby, also limiting each other, so that none of them become excessive and hamper spiritual development).

Scripture is important. It helps keep Christians unite with a central reference they can use to communicate with each other. But, with such a centering, they are also free to develop various insights which they need for the time and place in which they live. So long as Scriptural meaning is viewed as open-ended in this fashion, Christians are able to continue to thrive in the Spirit, but once one or another interpretation becomes set down as if it alone must be believed, the purpose of Scripture has been overturned and it becomes a dead letter. Scripture is meant to inspire us. To direct us. To help us become the people of God, the people who reveal themselves as children of God by the way we love one another and our neighbor as ourselves. But when we become too excessive in promoting our own limited understanding of Scripture, this gets lost, and even the best intentions lead to dead-ends. This is why it is invaluable for us to learn from others, to see what they have discerned from Scripture. This allows us to be ready to learn new truths from Scripture. This also makes sure that as we continue our walk with God, we go in the right direction, recognizing and respecting the incomprehensible nature of God and the ever-greater glory we have yet to encounter. For God is far greater than anything which we have already experienced or understood. Sadly, those who try to limit Scripture end up also limiting God to what they can comprehend, turning God into an idol instead of the boundless God of love.

[1] Hugh of St. Victor, The Didascalicon. Trans. Jerome Taylor (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961; repr. 1991), 102.

[2] Nicholas of Cusa, “To the Bohemians” in Nichola of Cusa: Writing on Church and Reform. Trans. Thomas M. Izbicki (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), 23.

[3] We must not confuse the meaning with the form in which the meaning came, which is why Paul said we are to follow the spirit and not the letter of the text if we want to have a lively spirituality.

[4] This is not to say we should accept bad readings of Scripture. We must recognize that not all bad readings are equal, and so not all are equally important for us to refute. Those which are relatively benign should not be our focus.

[5] St. Augustine, Confessions. Trans. Vernon J. Bourke (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1953; repr. 1966), 388.

[6] St. Augustine, Confessions, 399.

[7] St. Hilary of Poitiers, The Trinity. Trans. Stephen McKenna, CSSR (New York: Fathers of the Church, Inc., 1954), 36.

[8] This principle in hermeneutics is one which is universal, and not just with Scripture.