Christians, even in the ante-Nicene era (as can be seen in the catacombs), created and used images in their places of worship. The human spirit wants to express itself in and through images, through symbols and works of art which present those symbols, for we realize that through them, we have a way to access and experience the kingdom of God.

Historically, Christians first act out their beliefs in worship, so that through their prayers, they demonstrate what they believe. Lex orandi, lex credenda. But as time goes on, those beliefs sometimes become questioned. This is why theological explanations for how they worship comes long after particular practices have been developed and embraced by the community of faith. For it is only later, when someone does not understand various liturgical practices and symbols, usually because they do not understand the tradition behind them, that people begin to question what is being done. This is why it should not be surprising that the theological reasonings which are given to support the creation and use of images in the Christian faith came long after their use. Once some people questioned that tradition, once some contended that images should be forbidden, that their use was idolatrous, some of the faithful rose to defend such images, offering theological support for their way of life.

Christian iconoclasts usually raise the same kinds of questions: does not Scripture tell us to avoid making images of anything in heaven or on earth? Do not images themselves betray their non-Christian, and therefore pagan, origins, as many of them can be seen as being developments from particular pagan myths and images and the symbolic traditions surrounding them? Should not Christians follow the example of Scripture and destroy images wherever they are found?

The first round of the iconoclastic crisis (c. 730 -787 CE) had many images destroyed, all in the name of God, while great theologians, like St. John of Damascus, showed how the incarnation implicitly allowed for and expected the use of images for the Christian faith. The key argument was Christological: God became man and took on human form; by having human form, he took on an image for himself. If God can use images, so can we. Before the incarnation, it was not possible, for the divine nature is incapable of being imaged, even as it is incapable of being named, but God became man, and so what is beyond our comprehension meets us in human form and gives us the means by which we can represent him to the world. Likewise, the second Council of Nicea (787 CE) affirmed the appropriateness for Christians to make images, to bow down and venerate them.

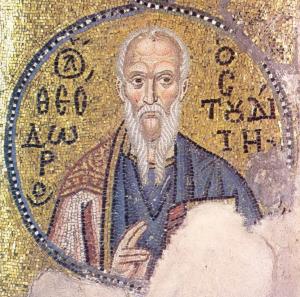

While the first iconoclastic crisis was brought to an end, iconoclasm would make a comeback under the Byzantine Emperor, Leo V, around 814, and would continue beyond his death, only coming to an end in 842. One of the great promoters of icons during this era was the great monastic and spiritual leader, St. Theodore the Studite (759-826). Indeed, Tomáš Špidlík wrote, he can be seen as one of the greats of his era: “The first great name to present itself in Byzantine times is Theodore the Studite (d. 826), a reformer of monastic life ‘according to the Fathers’, in the spirit of Basilian cenobitism.”[1] Theodore worked as a monastic reformer (Studite monk) in Constantinople, and much of his work and activity went towards the development of the Studite legacy. Nonetheless, most people remember him primarily for his defense of icons in the second iconoclastic controversy. He, and the Studite monks under him, protested Leo’s attempt to reintroduce iconoclasm within the empire by having a procession holding up icons on Palm Sunday. When the newly elected Patriarch, Theodotos, indicated his desire to follow the emperor and demand the church followed along with such iconoclasm, Theodore was sent into exile. Later, Theodore was tortured after he wrote asking for the Patriarchs in Rome, Alexandria, and Jerusalem to support him in his efforts to defend the use of holy images. Eventually, weakened from all he had suffered, he was allowed to return to Constantinople. If his enemies thought he would then be silent, he was not; he continued his work with those promoting icons, though of course, he was not able to be as aggressive in his campaigns as he was before his exile.

In many respects, the second iconoclastic crisis returned to the debates of the first crisis, centering on what Christology could say on the matter. St. Theodore, following Chalcedon, thought that the answer to many of the debates lay with the two natures of Christ. God, he accepted, was beyond images, and in his divine nature, could not be imagined; but in Christ, God became man and the human nature came to us in human form, and so could be portrayed:

As the properties of each nature cannot be changed, circumscription applies to the humanity of Christ; if Christ could not be represented according to his humanity, this would entail surely that this humanity had been moved away; and if it had been moved away, where had it taken residence? Perhaps into the nature of his own divinity? And if this is the case, the Trinity receives an addition, assuming a property that is not connatural (asmphyes) to it, which is impossible.[2]

Chalcedon explained that the natures of Christ, his humanity and divinity, are unconfused, and so remain as they are. In Christ, the divinity is not transformed to humanity, nor are they merged together to form some third thing. Rather, he is God and man. When we see him, we see him because of his humanity, and in that humanity, we have contact with the divine person (and therefore, with the divine nature). Nonetheless, we do not see the divine nature as such. The divine nature was uncircumscribed before the incarnation and so remains uncircumscribed in the incarnation; however, the person of the Logos assumed human nature, so we can and do see and encounter the divine person in his human form, and it is that form which allows for the divine person to be portrayed. To deny this is to deny the incarnation:

Therefore. Christ is circumscribed, even if he is not a mere human being (he is not one of the many, but God becoming a human being); else those whom you follow, and who say that Christ only came in appearance and as it were in a phantasy, would be attacked by the swift dragons of heresy. And yet, if he is truly God made man, he is also uncircumscribed, so the impious dog who laughably suggests that Christ had his origin from Mary may be chased off. This is indeed the new mystery of the economy: an encounter (synodos) has taken place between the divine and the human nature in the one hypostasis of the eternal Word, which preserves in an intact manner the properties of each in the undivided (diaretō) union. [3]

Portraying Christ, or anyone in an image, gives us a way to be in contact with Christ, or the person in the image, so that we can honor them as they deserve. It is not the image, in and of itself, which is the point, but the person being imagined:

To begin, every artificial image is a likeness (homoiōsis) of the one of whom it is an icon, and in itself it mimetically displays the imprint of its archetype, as Denys – expert in divine matters – says: truth in similitude; the archetype in the icon; one in the other, according to the difference in substance. Thus, the one who venerates the icon clearly venerates the one whom the icon displays. Indeed, he did not venerate the substance of the icon, but the one who is depicted in it; nor, indeed, as far as the veneration is concerned, did he separate the archetype from the icon.[4]

We honor people differently, according to the honor which they deserve. There is not only one kind of honor. There is not only one form of veneration. Nor is there only one way to interpret any act of veneration. We can perform the same act, say, bowing down to someone, but mean different things with that act, based upon the kind of honor we think the person deserves. If we, like Jacob, bow down to a family member (Esau),[5] we are showing them respect because of their relationship with us; if we bow down to an image of Mary, we are showing her respect for the greatness which God did in and through her; if we bow down to an image of Christ, we are elevating ourselves to an act of adoration, as we are now honoring God. The same act, but different intentions, demonstrates the relative nature associated honor being given in and through images:

If, then, a person is cognizant of the difference (diaphroa) in veneration, by means of which through the images the prototypes are venerated, he then has offered the veneration that is properly so called and that is properly offered to God alone; but to the other images, veneration is offered by analogy, to the Mother of God as to the Mother of God, and to the saints as to the saints. [6]

Likewise, if we honor someone of lesser glory, this does not mean we neglect those of greater glory. Honoring Mary and the saints does not mean we honor God less: rather, it means we will be able to honor God more:

If that which is inferior and lesser in honor is properly considered, only a foolish person would claim that which Is super and greater in honor is not properly considered. [7]

St. Theodore, then, helps us understand why honoring God and the saints through images, whatever images we use for them, does not make us confuse the saints, or anything else which we honor, with God. Likewise, then, we should not confuse the actions of others, if they act in a way of reverence which is different from the way we show it, as being idolatry if they already know and understand the relative difference between the person they honor and God. Honor can be given to many things, to created things, because of the glory of God which shines in and through them. We can honor God in and through his creation: indeed, through the incarnation, we are shown we are expected to do just that. We honor God when we honor the goodness which he established in his creation.

The legacy of the iconodules, like St. John of Damascus and St. Theodore the Studite, is important, because it explains how and why can use images for worship. We can honor God through his saints, as well as in all things in which his grace can be recognized: even Mother Earth can be honored (as represented by many medieval saints and Christians alike) so long as Mother Earth is understood as being one of God’s many wonderful and honorable creations. Those who suggest we cannot give relative honor and respect to the things of the earth have undermined what it means to worship. They have reduced the faith itself, and in doing so, end up offering God lesser honor by rejecting the glory which he has shared across creation.

Likewise, as we can use images, we can do so following many different cultural norms. We are not expected to reduce images to one form or style. The nations of the world, as Paul Evdokimov explained, have much to offer God, including the way they glorify God through the arts:

St. Paul tells us that, “we are co-workers with God” and Revelation says that “the nations bring their glory and honor.” The nations thus do not enter the Kingdom of God with empty hands. It is not difficult then to believe that everything that brings the human spirit closer to truth will enter the Kingdom of God. Everything that the human spirit expresses in art, discovers in science, and lives in the light of eternity, that is, all the heights of its genius and holiness will be integrated into the Kingdom and will coincide with their truth in the same way that an inspired image is identical with its original.[8]

Those who would reject one cultural form or expression of God, one style of images, calling the style itself idolatrous, give the foundation necessary to deny the use of images as a whole. It is why their arguments end up recycling the claims of the iconoclasts. The ancient Byzantine iconoclasts argued against the images of the culture which they knew, understanding how those images developed from a pre-Christian sensibility and employed and engaged symbols and images which came from “pagan” sources. The same will be true no matter where Christians employ the various cultures of the world. They will borrow from non-Christian sources, but they will transform them; just as images of Orpheus turned into Christ no longer can be said to be Orpheus to the Christians, images of Pachamama used to represent Mary are no longer Pachamama to the Christian. Yes, to the pagan, they can still represent Pachamama, just as to the pagan, images of Christ can still be seen to represent Orpheus. For Christian, all things are transformed as they are handed over to Christ; they are seen in the new light, in the light of Christ, so that no idolatry remains even if the images used once were used for idolatrous purposes. In this way, Bulgakov is right, when he reminds us that it was paganism, more than anything else, which gave us the resources we need to create holy images:

For us at the present time, when the battle against idolatry has only a historical significance, the difference between idols and icons is much less clear than what is common between them: the recognition of the Divine world can be represented in images of the human world (and even images of the animal world and of the whole created world in general) with the resources of art, as well as the recognition that these images are worthy of veneration. Paganism bequeathed Christianity an already developed idea of the icon as well as the fundamental principles of iconography (planar images with reverse perspective, methods of representation, ornamentation, etc.). [9]

Yes, holy images emerged from pagan cultures, indeed, from idolatry, but they are no longer idols, even as a baptized person is no longer contained in the Old Adam. Christians need not be afraid. God became man and has taken on humanity and allows us to present him in images, images which derive from the old but are made new in Christ.

[1] Tomáš Špidlík, The Spirituality of the Christian East. Trans. Anthony Gythiel (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1986), 12.

[2] St. Theodore the Studite, “Some Questions Posed by the [Same] Theodore to the Iconoclasts,” in Writings on Iconoclasm. Trans. Thomas Cattoi (New York: Newman Press, 2015), 129.

[3] St. Theodore the Studite, “First Refutation of the Iconoclasts,” in Writings on Iconoclasm. Trans. Thomas Cattoi (New York: Newman Press, 2015), 48.

[4] St. Theodore the Studite, “Letter of the Same Theodore to His Own Father Plato about the Veneration of the Sacred Images,” in Writings on Iconoclasm. Trans. Thomas Cattoi (New York: Newman Press, 2015), 135.

[5] Cf. Gen. 33:1-3.

[6] St. Theodore the Studite, “First Refutation of the Iconoclasts,” in Writings on Iconoclasm. Trans. Thomas Cattoi (New York: Newman Press, 2015), 59.

[7] St. Theodore the Studite, “Second Refutation of the Iconoclasts,” 73.

[8] Paul Evdokimov, The Art of the Icon: A Theology of Beauty. trans. Steven Bigham (Redondo Beach, CA: Oakwood Publications, 1990), 70-1.

[9] Sergius Bulgakov, Icons and the Name of God. Trans. Boris Jakim (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2012), 7.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!