Palladius, in the Lausiac History, relates of a remarkable story of St. Moses the Ethiopian. When he found four robbers in his monastic cell, St Moses being a big, strong man, was able to subdue them:

He tied them all together like a package, put them on his back like a bundle of straw, and took them to the church of the brethren. “Since I may not hurt anyone,” he said, “what do you want me to do with these?”

The robbers confessed and knew that he was Moses, the onetime notorious and well-known robber. They glorified God and spurned the world because of his conversion. For they reasoned, “If he who was such a strong and powerful thief fears God, why should we put off our own salvation?” [1]

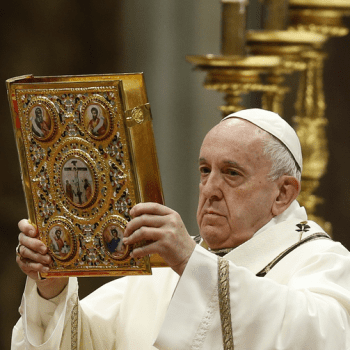

During his life, St. Moses’s fame spread far and wide. His life story was extraordinary. He was once a slave to a well-to-do official, perhaps a sun-worshiper, but his master could not control him. Moses’s destiny was with the monks of the desert, to be a great and holy priest. But before Moses could attend such a position, he had to make due with what he could with his life, and so he became a murderous robber, as Sozomen narrated:

Moses was originally a slave, but was driven from his master’s house on account of his immorality. He joined some robbers, and became leader of the band. After having perpetrated many evil deeds and dared some murders, by some sudden conversion he embraced the monastic life, and attained the highest point of philosophy.[2]

It has been said that when he was on the run, he once looked up to the sun, and asked if it (or anyone) was God. He wanted God to reveal himself to him. Eventually, he heard that the desert fathers at Wadi El-Natroun knew God. Moses went to the monastery and met the priest Isidore. At first, Isidore was afraid, thinking Moses was there to do him harm. But when Moses told him not to be afraid and that he had come to learn about God, Isidore’s fear rescinded. Isidore took him to meet St. Macarius who then undertook Moses’s Christian education and initiation.

Moses became one of the great monks of the desert, at first fighting his own internal demons and doing penance for his previous life of crime, but eventually being called to the priesthood and to become one of the leaders of the monastic community. The process of transformation was not easy. He had to completely change his way of life. He had several bad habits which he had to fight off, including, but not limited to violence and lust. But he understood the need. As he renounced the path of violence, he learned the lesson of forgiveness. People, including and especially sinners, need compassion if they are going to be saved from their worst inclinations.

As Palladius indicated, his method had much success: his compassion for sinners, based in part on the forgiveness which he received for his sins, demonstrated the love and understanding Christians should have for others. Sadly, this is something many, if not most Christians, have forgotten. How many of us think, not along Christian lines of mercy and grace, but along the lines of secular power and its failed methods to control criminals, from jailing criminals without compassion to the death penalty? We can only imagine what many so-called Christians would have done if St. Moses the Ethiopian was alive today: far from giving him a chance to convert to the Christian faith, they would have demanded he be put to death. While there might be need for prisons, prisons should be run with the desire to truly reform criminals. Just because they have committed crimes does not mean they should not be shown dignity and respect; indeed, it is understandable why they do not try to change their ways when society has already treated them as lost causes.

Nonetheless, many who would be the first to promote the death penalty think they can honor and respect St. Moses the Ethiopian at the same time. Why? Because he does not challenge them. He is a figure from the past. They do not have to work with him and help him change. And if someone else, like Moses, came before them, a reformed robber who has undertaken the path to holiness, would they acknowledge his conversion? Would we? It’s easy to say we would, but the way society treats reformed criminals, it is also easy to see how unlikely this is the case. Jesus himself warned us against such hypocrisy: “Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for you build the tombs of the prophets and adorn the monuments of the righteous, saying, `If we had lived in the days of our fathers, we would not have taken part with them in shedding the blood of the prophets’” (Matt. 23:29-30 RSV). We all tend to think we would recognize saints, and not mistreat them, but the reality is, it is difficult to know when a saint is before us and if we do not show compassion for all, it is easy for us to see how and why we would end up persecuting saints today similarly to the way saints in the past were persecuted.

If we do not want to fall under Jesus’s rebuke, we must recognize that there are many potential St. Moses’ in the world. There are far too many people with troubled pasts who turned to crime because they knew nothing better. When they are arrested, what happens to them? Do we care? Usually, we let the system take them in, grinding them further down; but if we, in our sins, have been given grace, and can be saved through it, we should likewise seek their well-being, doing all we can to make sure the systematic injustice in our current penal system do not end up destroying their human dignity, making it near impossible for them to have their life transformed. Society is responsible for them and what happens to them. Indeed, society created the situation in which they found themselves so desperate that they turned to crime; in this way, we can be said to share in their crime, sometimes with more guilt than those who commit the crime because we had more power to change the situation and make sure they did not end up so desperate. St. Moses knew this, which is why he helped the robbers who came to his cell; this story was one of many which demonstrates he was a major voice for mercy and grace, making sure the monastic community remembered that their prayers for mercy for themselves meant that they should give mercy to others. He said that what we said in our prayers, such as the Lord’s prayer, must be balanced out by our deeds:

If a man’s deeds are not in harmony with his prayer, he labours in vain. The brother said, ‘What is this harmony between practice and prayer?’ The old man said, ‘We should no longer do those things against which we pray. For when a man gives up his own will, then God is reconciled with him and accepts his prayers.’ [3]

The selfishness shown by many Christians as they want mercy, grace, compassion, and love for themselves while they are unwilling to show it to others, especially those who are in most need of mercy, indicates the imbalance found within modern Christianity. Thoughts and prayers are good, but if they are not balanced out and harmonized with deeds, they become a farce. Moses proclaimed the authentic Christian way of life, where thoughts and prayers are joined in with deeds which enact the words said in our prayers. We can and should have confidence in the potential we have when we unite true Christian prayer with true Christian action, where we work for the common good:

Such is the confidence that we have through Christ toward God. Not that we are competent of ourselves to claim anything as coming from us; our competence is from God, who has made us competent to be ministers of a new covenant, not in a written code but in the Spirit; for the written code kills, but the Spirit gives life. Now if the dispensation of death, carved in letters on stone, came with such splendor that the Israelites could not look at Moses’ face because of its brightness, fading as this was, will not the dispensation of the Spirit be attended with greater splendor? For if there was splendor in the dispensation of condemnation, the dispensation of righteousness must far exceed it in splendor. Indeed, in this case, what once had splendor has come to have no splendor at all, because of the splendor that surpasses it. For if what faded away came with splendor, what is permanent must have much more splendor (2Cor. 3:4-11 RSV).

This was something St. Moses had to learn for himself. Even when he had turned away from his life of crime, he still had a long way to go for perfection. He struggled with his internal demons, from the experiences, habits, and desires he had developed from his past. As a monk, he followed the ascetic discipline of the desert community, and although it helped, it was not sufficient. It was when he moved on to a life of charity when he found success:

He stayed in his cell six years then, standing in the middle of his cell every night praying, never shutting his eyes—and still he could not control his mind. He started another way of life. Each night he went out to the cells of the old men and the more ascetic of them, and he took their pitchers and kept them filled without their knowledge. For they have their water a good way off – some two miles, others five, and some only half a mile.[4]

Once he went beyond ascetic practices and started to act in charity, Moses was transformed. He acted upon the grace which he received, finding ways he could humbly help others. In doing so, grace elevated him, making him far greater in Christ than those who would look down upon and denigrate anyone who had once been a murderous criminal. The Christian faith is a faith which trusts in the goodness of God, and so, it is a faith which allows for sinners to reform. The Christian faith is a spirit beyond the letter of the law, knowing that the law should be intended for our own good. Those who hold to the letter of the law often follow the path of death as they use the law to promote death of others; on the other hand, those who hold to the spirit of the faith, those who know the spirit of truth and goodness, seek life for all; how many potential saints have been executed by those who give in to their murderous rage with the death penalty? Because St. Moses the Ethiopian, who had once been a slave, a robber, and a murderer, was taken in by Isidore and Macarius, and shown the love and respect he had not previously known, he became one of the great and most beloved desert fathers. Thankfully, St. Moses was not executed, but given a chance to be the man God intended him to be, the great, loving, merciful, promoter of non-violence who could inspire us all.

[1] Palladius, The Lausiac History. Trans. Robert T. Meyer (New York: Paulist Press, 1964), 68.

[2] Sozomenus, Ecclesiastical History in NPNP2(2):367.

[3] The Sayings of the Desert Fathers. trans. Benedicta Ward (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1984), 141-2 [from Seven Instructions Abba Moses sent to Abba Poemen].

[4] Palladius, The Lausiac History, 69.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!