God entered creation and became a part of it as a human man in order to save the rest of humanity. For many, this is all they understand about the incarnation. While it is true, it is not the whole of the truth. In reality, the incarnation is about the establishment of God’s deifying grace to the whole of creation, to elevate creation so that the whole of creation, and not just humanity, can participate in and experience the kingdom of God. Because of sin, God had to free all that has been tainted by sin from its corrupting influence, but that is not the goal of the incarnation: it is only a point along the way towards deification, the participatory union of all creation with God in and through the mediatorship of Jesus Christ.

Due to the nature of the incarnation, many Christians have erroneously thought that all that God was only concerned with the salvation of humanity. While it is true that there is something special about humanity (as there is with the Jews), this special nature is misunderstood when it is used to suggest God neglects or is not interested in the rest of creation. The fact that Jesus took on human nature in the incarnation should not make us think what God accomplished in Jesus was only for humanity. Just as we do not assume the Jewishness of Jesus means that the incarnation is only for the Jews, so the fact that Jesus assumed human nature does not mean the incarnation is only for humanity. Salvation is from the Jews (cf. Jn. 4:22), but it is not limited to the Jews. Salvation is from humanity, but it is not limited to humanity. Likewise, then, deification comes about from the incarnation, through Jesus as a Jew, but the deifying grace is spread throughout the whole of creation.

Though Scripture clearly suggests humanity is special, it also does so by pointing out God’s interest in the rest of creation. “Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they?” (Matt. 6:26 RSV). “What man of you, if he has one sheep and it falls into a pit on the sabbath, will not lay hold of it and lift it out? Of how much more value is a man than a sheep! So it is lawful to do good on the sabbath” (Matt. 12:11b-12 RSV). In both of these texts, Jesus tells us that God truly has concern for animals; in the first, God is said to have some providential care for the birds, the second, God is willing to acknowledge the need for humans to take care of their animals if they are in need on the Sabbath. In both instances, Jesus did not deny the special status of humanity, but on the other hand, both statements are based upon the postulate that God takes care of and is concerned with animals and not just humanity. Take away God’s providential care for animals, and the consequences Jesus implied by Jesus’ words will be lost. Jesus presumes care and concern for animals is proof that God cares for humanity.

It should not be surprising this concern is found within the Law of Moses, even with the Ten Commandments. The Sabbath is for humanity, but it is also for the animals:

Observe the sabbath day, to keep it holy, as the LORD your God commanded you. Six days you shall labor, and do all your work; but the seventh day is a sabbath to the LORD your God; in it you shall not do any work, you, or your son, or your daughter, or your manservant, or your maidservant, or your ox, or your ass, or any of your cattle, or the sojourner who is within your gates, that your manservant and your maidservant may rest as well as you (Deut. 5:12-14 RSV).

Likewise, the Law of Moses found itself concerned with the prevention of animal abuse, such as when it was declared, “”You shall not muzzle an ox when it treads out the grain” (Deut. 25:4 RSV). The presentation of the peaceable kingdom of God, found in the book of Isaiah (cf. Is. 11:6-9) is inclusive of animals: they were created by God, they were seen as good by God, and so they have a place in the eschaton with the rest of the world. The new creation, the new earth, the transformed earth includes them because God is concerned with them as he is with the rest of his creation.

Through the work of Jesus Christ, all things are brought together as one so that they can be rendered over to the Father and participate in the divine life. Sergius Bulgakov, therefore, explained how we must rethink what we mean when we talk about the end of the world, to realize it is about a change that the whole of creation undergoes, a change which will bring it all into glory:

The end of the world is not physical but metaphysical. In reality, the world does not end but is transfigured into a new being, into a new heaven and a new earth. The changes that will take place in it will not be limited to a new combination of the same cosmic elements and the actions of previously existing cosmic forces. Rather, a new supercosmic force will enter the being of the world and transform it. The introduction of this force will affect the entire physical structure of the world, but it will be preserved in its natural being. However, the latter will open up to receive a new element of being: “glory.” And this appearance of glory, the glorification of the world, will inwardly change all the elements of its being, will impart a new quality to them.[1]

This transformation is established in and through Jesus Christ. The whole of creation is given the gift of deification. God became human but by becoming human he took on a created nature, thereby sharing in and being united with all things which have a created nature. St. Maximos the Confessor, understanding this, said:

For Christ unified the human being, mystically removing, by means of the Spirit, the difference of male and female, freeing the principle of nature in both from the properties characteristic of the passions. He also united the earth, driving away the variation between sense-perception paradise and the rest of the world. He united earth and heaven, demonstrating that the nature of sensible things is one and inclines toward itself. He also united sensibles and intelligibles, and demonstrated that the nature of the things that have come into being is one, being conjoined according to a certain mystical principle. According to a principle and mode beyond nature, He united created nature to the uncreated. And at each unity, that is, at each corner, He built and fortified the supportive and connective towers of the divine doctrines. [2]

Humanity can be seen as the cornerstone by which Christ united the whole of creation as one, taking on various natures because of humanity’s relationship to those natures. Humans are animals, so Christ took on animal nature in becoming human, and in doing so, can be said to have made all animals, including humanity, one in him. Generalizing more and more, St. Maximos demonstrated how, by becoming human, Jesus assumed a created nature, unifying all those with a created nature as one in himself so that they can then share in the glory of God, to be moved beyond themselves through deification. Everything, even those things which we think little of, are brought together and elevated by Christ:

For according to the true doctrine, all beings after God which possess their being from God by virtue of having been created by Him, coincide with all the others (even if not in absolutely all respects) – and in general no being, including those from among the greatly honored and transcendent, is completely free by nature from the condition of general relation to what is Itself totally unconditioned, nor is the most ignoble among beings completely destitute or devoid of a natural share in the general relationship to the most honored beings. [3]

Some Christian theologians point out that what Jesus accomplished was, in part, what humanity was expected to accomplish. That is, humanity was intended to make the world into a glorious “garden of God.” Humanity, for a time, followed its proper mission, which is how and why Adam was shown to be in the garden of Eden, in an earthly paradise, which he watched over and helped guide to completion:

Indeed, he was called to transform the entire world into this garden of God. Thus, even nonhuman nature was to a certain degree entrusted to man’s creatively for the purpose of being elevated to perfection and fullness.[4]

But something went wrong, and humanity lost site of its mission in the world. It selfishly looked within, to the inordinate pursuit of pleasure over goodness, to justify itself as god of the earth which demanded sacrifice and praise from the earth instead of being the good and glorious steward of the earth who took care of it for the glory of God. The elevation of the earth, far from being performed by humanity, was hindered by humanity in its selfishness and pursuit of dominance. The task which humanity intuitively understood was its own, an intuition which was remembered and embraced the world over by its myths and legends, finds its fulfillment in Christ. He is the expectation of the nations, but he is also the expectation of the whole of creation. In this manner, then, Christ, who became a particular Jewish man, did not ignore the rest of humanity nor the rest of creation: animals, plans, even non-living matter, all find Christ working for them. They are not ignored.

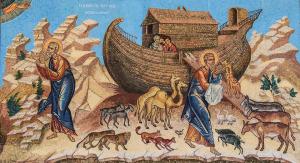

Should we really be surprised by this? God has shown us he cares not just for humanity but for all his creation. If we look at the great prefiguration of the church, the story of Noah in Genesis, we find that it is not just humanity who has been saved. God made it clear that animals needed to be saved as well. Christians should not neglect the implications presented to it by Noah’s Ark. Humanity was saved, but it was saved side by side with the rest of animal kind. Noah was told to take care of and watch after animals, to make sure they were not lost, and so they were saved in and through Noah, even as Noah was saved by God.

Of course, as Jesus brings not just salvation, but deification to all things, we must wonder what this means for animals (and plants, and everything else which exists). Does it mean, as some suggest, that they are to be merely “hominized”? But if that is the case, if they are to become like humans, and humans are to be deified and made greater than their own nature, does that not suggest that will follow humanity and continue to become ever greater through the grace of God? What we do know is that God cares for them, and somehow, in and through humanity, they are meant to be elevated with humanity, just as they are saved alongside humanity. For as Noah’s Ark brought humanity and animals to earthly safety, so the eschatological ark, the church, will bring humanity and the rest of creation together to the other shore, to the kingdom of heaven.

[1] Sergius Bulgakov, Bride of the Lamb. Trans. Boris Jakim (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002), 401.

[2] St. Maximos the Confessor, On the Difficulties in Sacred Scripture: The Responses to Thalassios. Trans. Fr. Maximos Constas (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2018), 269-70. [Question 48]

[3] St. Maximos the Confessor, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua. Volume II. Trans. Nicholas Constas (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 115-117[Amb.41].

[4] Sergius Bulgakov, Bride of the Lamb, 150.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!