We are made in the image and likeness of God; while sin has defaced us, blotting out that image, the teaching of the Christian faith is that Jesus came not only to heal us from the defilement of sin, cleansing that image and making it visible again, but to deify us, to make us greater what was given to us at creation.

We must not consider our nature to be static: though it is good, though it is meant to imagine and present a representation of God to the world, it is not a closed nature incapable of transcendence. We are called to participate in the divine life, to become greater and greater, to take on more and more of the divine life into ourselves, to become more and more like God, so that what we were according to creation will be far less, indeed infinitely less, than what we will be in beatitude. “In its ultimate glory and ultimate beauty and in the happiness promised it, the human soul will be similar to its creator.” [1] Not only will we be similar to its creator, we will become more and more like our creator as we are deified; this would not be possible if human nature were some sort of closed-off pure nature which limits our potential.

So long as we become attached to ourselves, to the form which we think we are meant to be, incapable of transcending that form, we will cut ourselves off from what God intends for us. Satan, it is said, fell due to pride, pride in the glory which he saw in himself, a glory which he became so attached to that he was unwilling to go beyond himself and take the deifying grace of God which would have led him to become something even better. It is this pride which limits us: by trying to hold on to some false notion of the self, to some false notion of human nature, kept pure in and of itself, we lose even what we originally had, but if we, on the other hand, open ourselves up, see the fluidity of our nature when it is mixed with grace, we will be able to grow beyond our initial stage of being into deified beings. Thus, our walk with Christ must be seen not only as the restoration of the divine image within us, but the growth of that image as we ascend to God.

It is not by nature but by grace this is possible. “For nothing created is by its nature capable of actualizing divinization, since it cannot grasp God. For this is the property of divine grace alone, that is, to grant the gift of divinization proportionally to created beings, brightly illuminating nature by a light that transcends nature, actively elevating nature beyond its proper limits through the excess of divine glory.”[2]

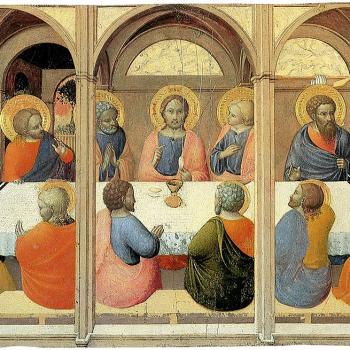

If we are transformed to be like God, truly imagining God in our being, we will act like he acts. According to some of the Tannaitic sages, this means we will be longsuffering, showing mercy and grace to others just as God shows it to us:

Abba Saul says, “It means that one should imitate Him. As He is gracious and merciful, so should you be gracious and merciful.”[3]

When we are far from this, when we do not represent the love of God to others, we must work with grace to transform ourselves, to purify ourselves from all that is unlove, that is, all that which is sin or tempts us to sin. Spiritually speaking, this is what most of us are called to do, to engage an active life in the world, transforming ourselves so that we imitate the benevolent acts of God towards others. Julianus Pomerius, who hoped to lead his readers beyond the active life and into the contemplative life, nonetheless understood the active life was needed before one was ready for the contemplative life; he explained what was expected of us in that stage of our spiritual evolution:

The follower of the active life, by harboring the stranger, clothing the naked, governing the subject, redeeming the captive, protecting him who is oppressed by violence, is continually cleansing himself from all his sins and enriching his life with the fruit of good works.[4]

The more we follow the principles of love, the more we reflect love, the more sin is removed from us and the more godlike we reveal ourselves to be. The dictates of the law and prophets, the dictates of Jesus in the Gospels, tell us what this means: the active life is a life seeking justice for those who suffer injustice, a life of charity to those who need to experience love and grace, and a life of self-discipline which helps us move after any undue attachment to false notions of the self (and human nature) so that we freely receive the transformative grace of God in our lives.

If we transcend the active life and find ourselves ready for a contemplative life, it will be a transformation which does not deny active life, but rather will establish us in a contemplative life which continue to work for and engage the needs of others. We might do so in different ways, but the point is we will not be selfishly attached to ourselves and our own desires; we would forego contemplation if it turns us away from a godlike life. The contemplative life is good, but it can be dangerous when it is engaged by those without proper spiritual preparation or direction, that is, by those who continue to be trapped with a love for the self alone instead of love for all.

The contemplative life is for those who have overcome a base mind, for what is in the mind will be reflected back at us in our meditation. The active life helps purify the mind, making it reflect God from within as we turn it into an image of love. On the other hand, insofar as our hearts and minds remain defiled, when we engage a contemplative existence, we will see and experience things according to that defilement; sometimes it will not cover up our experience, and we will receive something good, but sometimes it will cover it up, causing us to encounter God and the world in monstrous forms. This is why the active life is first, and we must judge to see if our mind is base or not, if it still suffers from the defilement of unlove. Origen, then, explained what we should look for to see if we still have a base mind, defiled mind which needs to be transformed by an proper engagement with the active life: “For example, it is certain that a man who is filled with iniquity, malice, profligacy, and greed has not approved to acknowledge God and belongs to the number of those whom God has handed over to a base mind.” [5] What we must seek is an active life where the passions generated by sin are overcome. Once this is established, we have truly fulfilled the active life and can be said to truly engage it in full, and we will continue to do so when we engage contemplation. “A mind engaged in the practical life is one that always receives the mental representations of this world in a manner free from passion.”[6]

God is love. We are called to be reflections of that love. When we free ourselves from the defilements of unlove, thanks to the active life, then we will be able to see God all in all, both outside of ourselves but also within. This should be our goal, to see God in all things, so we can love all things. The Father loves the Son, and the Son loves, the Father, forming a bond of love between the two of them, the bond of the Holy Spirit. We, too, are called to love, to be beings of love, reflecting the love found within the Trinity. God will love us, and we will love God, with the bond which ties us together, the bond of the hypostatic union of the God-man, Jesus Christ. But if we want to assume some closed, static nature for ourselves, we will never know this love, for “no eye has seen, nor ear heard, nor the heart of man conceived, what God has prepared for those who love him” (1Cor. 2:9b). Thus, let us welcome the transformative grace in our lives, to accept what God desires for us instead of closing it off due to our own conceptions of human nature, conceptions which come from what we have seen and heard from the past instead of what we can receive in eternity.

[1] William of Auvergne, The Trinity, Or The First Principles. Trans. Roland J. Teske, SJ and Francis C. Wade, SJ (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 1989), 172.

[2] St. Maximos the Confessor, On Difficulties in Sacred Scripture: The Responses to Thalassios. Trans. Fr. Maximos Constas (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2018), 153.

[3] Reuven Hammer, trans. and ed., The Classic Midrash: Tannaitic Commentaries on the Bible (New York: Paulist Press, 1995), 104.

[4] Julianus Pomerius, The Contemplative Life. Trans. Mary Josephine Suelzer, PhD (Westminster, MD: The Newman Bookshop, 1947), 32.

[5] Origen, Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans: Books 1-5. Trans. Thomas P. Scheck (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2001), 100.

[6] Evagrius, “Reflections” in Evagrius of Pontus: The Greek Ascetic Corpus. Trans. Robert E. Sinkewicz (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 212.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you have liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!