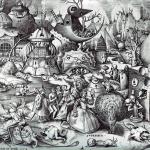

Nothing is so quick to turn us away from the good than by seeking praise and honors for doing so, because once we become accustomed to accept such praise as signifying what is good and just, we will find ourselves malleable to the whims of what is temporarily popular. We shall change our ways, we shall change what we do, in order to continue to receive accolades from others. What could be more fickle than that? We might get what we desire, but we will find it is fleeting: the praise is momentary, while life continues on. We will find out that when we get such a reward that it does not satisfy us. When our fame dies down, we will have to do something once again to gain the attention of others, and the more we act in the ways we think will get us praise, the more we will find ourselves transformed, doing only what it takes to receive the attention we desire.

Why do we do this? Why do we seek out such vain glory? It is because we are attached to ourselves, we love ourselves and the good which we see in ourselves. Truly such good might be worthy of being praised, insofar as it is good, but it should not be elevated beyond its proper status. Likewise, we should not be glorified and treated as being more than we are. Yet, as we love ourselves, we seek such glorification: it makes us feel good. It seems to justify our own self-attachment. We love ourselves, and so we love it when others love us. Once we become addicted to such praise, doing whatever we feel is necessary to continue to receive it. Indeed, the more we are tied to it, the more we find ourselves acting, instead of being, what we portray ourselves to be. “Sometimes a man cuts off a passion in order to indulge himself more fully, and he is praised by those unaware of his aim. He may even be unaware of it himself, and so his action is self-defeating.”[1]

Eventually, we will find ourselves not only out of favor, but incapable of receiving it again as others become the center of attention for a fickle public. And then what shall we do? What will this mean for us? Since our foundation was not in accordance with justice and reason, but the momentary satisfaction of an emotional desire, we will find ourselves out of luck: not only will our vanity no longer be appeased, we will find that we do not know what to do with ourselves, because we have acted according to the dictates of others and their vain opinions, and not reason. Vainglory, the desire for praise and glory and honors, is a terrible temptation because it leads us away from the good by deluding us with a partial, lesser good, which like a mirage, will one day desert us, leaving us wandering around a barren landscape without any understanding of where we should go.

Often, to be sure, we do not begin with visions of glory. Vainglory tempts us, and gets to us, often when we seek what is good and just, but then find ourselves and our actions receiving the praises of others. As we like the praise, we slowly find ourselves and our actions modified so that we continue to get it. We see what people like, and act accordingly; we begin, even, to repeat ourselves, hoping for repeat accolades. Sadly, this often leads to disaster. What is good at one time and place might become harmful when repeated. Vainglory, however, distorts our vision and so does not allow us to reason through our actions, discerning what was good about them, so we are more likely than not to act in ways which will harm not only us but our fawning public.

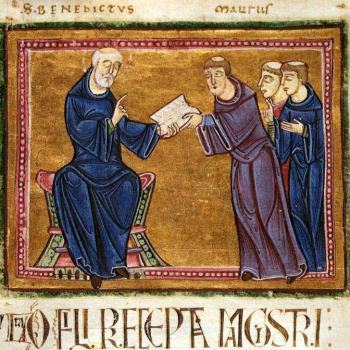

Vainglory is a special temptation for those pursuing religious holiness. Many who seek a name for themselves in religious circles fall for this error for this very reason: they begin with good intention, but without prudence, they fall for vainglory and then seek to be lifted up and praised by others, often by taking down and destroying the good which hinders the reception of such praise. To seek honor, to take and accept awards as signs of one’s value, is to accept the temptation of vainglory, and those who do so will find themselves set up for a terrible fall from grace. Indeed vainglory, that is the promotion of the self and its glory (hence, a bad kind of “self-esteem”), is something which plaques us throughout our spiritual journey. It is a vice which comes back at us again and again, attempting to thwart us from the fullness of the good with the comforts which it brings to us instead. Thus, St. Gregory of Sinai warns us, we can easily find ourselves daydreaming about our own glory:

For whether you are a beginner, or midway along the spiritual path, or have attained the stage of perfection, self-esteem always tries to insinuate itself, and it nullifies your efforts to live a holy life, so that you waste your time in listlessness and day-dreaming.[2]

Once we let vainglory divert us, what we have gained is easily lost, as we let our goal become subverted. What is good, can be good, but when we use it for our own vanity, to look good in front of others rather than for the good itself, we find that the good itself is hollowed out, making it vain, which is why we read in the book of Isaiah God’s displeasure with the vain impiety which lay behind the way many in Israel worshiped Him: “Bring no more vain offerings; incense is an abomination to me. New moon and sabbath and the calling of assemblies — I cannot endure iniquity and solemn assembly” (Isa. 1:13 RSV).

In this fashion, we find many actions which can be good, and lead us towards our proper end with God, can become subverted and turn us inward instead, worshiping ourselves and our own glory:

Like the sun which shines on all alike, vainglory beams on every occupation. What I mean is this. I fast, and turn vainglorious. I stop fasting so that I will draw no attention to myself, and I become vainglorious over my prudence. I dress well or badly, and am vainglorious in either case. I talk or I hold my peace, and each time I am defeated. No matter how I shed this prickly thing, a spike remains to stand up against me.[3]

So long as we focus on the good which we do and the glory we think we have earned as a result of that good, we abuse the good, making it a tool for our own spiritual destruction. This is not to say that there was no good achieved: often such good is achieved, and God is at work in and through that good for the benefit of others, but for the one who gives in to vainglory, that good is lessened, insofar as that vainglory is heeded. It can still be turned around and used for the greater good: but to do that, the vainglory must be removed and the true and full good, which lies beyond ourselves, must once again become our focus.

This is why Jesus, in speaking of doing good, tells us to avoid any attachment to that good ourselves:

Beware of practicing your piety before men in order to be seen by them; for then you will have no reward from your Father who is in heaven. “Thus, when you give alms, sound no trumpet before you, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, that they may be praised by men. Truly, I say to you, they have received their reward. But when you give alms, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your alms may be in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you. (Matt. 6:1-4 RSV).

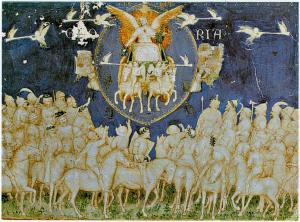

The proper reward, that which we truly should seek and desire, is the good which lasts, the good which God is able to and will bring to us in eternity. So long as we hold on to some temporal good as our desired end, if we get that end, we have received our reward, but it is a reward which shall not satisfy because of its temporal nature. If we seek after that which shall last, we might and likely will attain limited goods as well. There is no reason for us to deny them, so long as we enjoy them without attachment, without treating them as being more than they are. What is important is that we do not let ourselves be seduced by lesser goods, becoming so attached to them we lose our way; they are good, because they have been given to us by God, but we should receive them as temporary gifts which remind us of the greater and eternal gift of the good itself which we seek. That is, we must remember that it is not the temporary goods which are in error, it is our attachment to them which lead us astray. Vainglory comes when we attach ourselves to the honor and praises of others: it is not the honors and praises themselves which are necessarily bad, but our reaction to them which causes us trouble.

“Let us have no self-conceit, no provoking of one another, no envy of one another” (Gal. 5:26 RSV). Charity and humility, the fruits of love, are what we need to hold onto when we find ourselves tempted by vainglory. For by them, we see through the praises, and see that what we must seek is not our own self-promotion, but rather, the good itself, a good which lifts others up because it is right and just to do so. Love, the source and foundation of charity, after all, never looks to the self, but to the beloved, and so long as we look to the beloved, we will receive nothing which will move us to praise ourselves. On the other hand, when we see ourselves belittling others because we feel dishonored by them, we can see that the vice of vainglory is influencing us, and the more we react to such negatively, the worse we might be seen by others:

Vainglory induces pride in the favored and resentment in those who are slighted. Often it causes dishonor instead of honor, because it brings great shame to its angry disciples. It makes the quick-tempered look mild before men. It thrives amid talent and frequently brings catastrophe on those enslaved to it.[4]

Thus, it is best to avoid all pursuit of earthly honors. We should seek what is good and true, and not base that on the mere opinions of others. Then we can slowly move beyond the illusion of earthly glory as we hopefully receive a share of the divine glory. And once we do, then vainglory and its power over us will be destroyed. [5]

[1] St. Mark the Ascetic, “On the Spiritual Law” in The Philokalia: The Complete Text. Volume One. Trans. G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware et. al. (London: Faber and Faber, 1983), 117.

[2] St. Gregory of Sinai, “On Stillness,” in The Philokalia: The Complete Text. Volume Four. Trans. G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware et. al. (London: Faber and Faber, 1995), 272.

[3] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent. Trans. Colm Luibheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1982), 202.

[4] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 203.

[5] Thus, ““If we really long for heavenly things, we will surely taste the glory above. And whoever has tasted that will think nothing of earthly glory” St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 204.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook