![]() It is commonly accepted that St. Paul was not married. This is how his words, “I wish that all were as I myself am” (1 Cor. 7:7a) are generally interpreted, though it was also conceded that he thought that if he wanted to be married that he had the right to marriage like the other Apostles. “Do we not have the right to be accompanied by a wife, as the other apostles and the brothers of the Lord and Cephas?” (1Cor. 9:5 RSV).

It is commonly accepted that St. Paul was not married. This is how his words, “I wish that all were as I myself am” (1 Cor. 7:7a) are generally interpreted, though it was also conceded that he thought that if he wanted to be married that he had the right to marriage like the other Apostles. “Do we not have the right to be accompanied by a wife, as the other apostles and the brothers of the Lord and Cephas?” (1Cor. 9:5 RSV).

Nonetheless, there was a tradition, spread in the Alexandrian School of thought, and mentioned by Eusebius which suggested that Paul was actually married:

Clement, indeed, whose words we have just quoted, after the above-mentioned facts gives a statement, on account of those who rejected marriage, of the apostles that had wives. “Or will they,” says he, “reject even the apostles? For Peter and Philip begot children; and Philip also gave his daughters in marriage. And Paul does not hesitate, in one of his epistles, to greet his wife, whom he did not take about with him, that he might not be inconvenienced in his ministry.” [1]

In this interpretation, then, Paul was not saying that he had the right to marry, but rather, he had the right to take his wife with him in his ministry. If this is true, then what he meant when he said he wishes others were like him is that they would overcome desires of the flesh and seek service to Christ, ignoring the flesh, not because conjugal relations are evil, but rather, they could and would get in the way of service to Jesus. The context in which Paul spoke of others being like him comes after his statement that it is good for a man not to touch a woman, but it is better to have relations than to suffer from concupiscence and to be led astray from it:

Now concerning the matters about which you wrote. It is well for a man not to touch a woman. But because of the temptation to immorality, each man should have his own wife and each woman her own husband. The husband should give to his wife her conjugal rights, and likewise the wife to her husband. For the wife does not rule over her own body, but the husband does; likewise the husband does not rule over his own body, but the wife does. Do not refuse one another except perhaps by agreement for a season, that you may devote yourselves to prayer; but then come together again, lest Satan tempt you through lack of self-control. I say this by way of concession, not of command (1Cor. 7:1-6 RSV).

According to what Eusebius suggested, Paul wanted to focus on his ministry, and having his wife with him could cause him inconvenience. Not only would he have to watch over her, protecting her from possible harm for being around him, he would also find himself focused on her and her conjugal needs, as well as his own personal desires, so that he might possibly lose touch with apostolic mission. It was not that he would have thought marriage was bad, but that it could lead someone like him away from his focus on Christ. He wanted to be a slave to Jesus, and no one else.

Paul, as a zealous Jew, would have been raised to believe marriage was important; as a Christian, he came to see that importance change because the eschaton had become immanent in the world through Jesus Christ. For him, perfection would no longer required someone to be married so that they can have children and continue their familial legacy in the world, so marriage itself and its value became relativized. This is why, even if he were married, his relationship with his wife would be different after he became a Christian than before. St. Clement of Alexandria, who is a significant recorder of the tradition that Paul was married, suggested that the apostles who were married treated their wives as sisters, as fellow-workers in their ministry, and so Paul considered that it was more important for his wife to likewise be a fellow-worker with him in his ministry than it would have been to raise a family:

In one of his letters Paul has no hesitation in addressing his “yokefellow.” He did not take her around with him in convenience of his ministry. He says in one of his letters, “Do we not have the authority to take around a wife from the Church, like the other apostles?” But the apostles in conformity with their ministry concentrated on undistracted preaching, and took their wives around as Christian sisters rather than spouses, to be their fellow-ministers in relation to housewives, through whom the Lord’s teaching penetrated into the women’s quarters without scandal.[2]

Origen, likewise, knowing this tradition, briefly mentioned it in his commentary on the book of Romans:

Paul, if certain traditions are true, was called while in possession of a wife, concerning whom he speaks when writing to the Philippians, “I ask you also, my loyal mate, help these women.” [3]

We find this tradition also recorded in the lengthier version of the epistle of St. Ignatius to the Philadelphians:

For I pray that being worthy of God, I may be found at their feet in the kingdom, as at the feet of Abraham and Isaac, and Jacob; as of Joseph, and Isaiah, and the rest of the prophets; as of Peter and Paul, and the rest of the apostles, that were married men. For they entered into these marriages not for the sake of appetite, but out of regard for the propagation of mankind.[4]

Now, the lengthier edition of Ignatius’ letters seems to be from texts which were added to and developed by some secondary author or authors, but the fact that Paul was among those who were listed as being married in it suggest that the tradition that Paul was married was not unknown, and not too controversial, in the first couple centuries of church history. This is not to say it was the only tradition, nor the one which would become generally accepted; St. John Chrysostom gave in his homilies his view which was Paul was celibate and he was not talking to his wife: “Some say Paul here exhorts his own wife; but it is not so, but some other woman, or the husband of one of them.” [5]

Chrysostom’s view represented what was to be normally accepted about Paul, however, the notion that Paul was married, and his wife was, at least for some part of his ministry, still alive and involved active in the church, would make more sense from Paul’s own Jewish heritage. If we are to accept there is some truth to the notion that he was an associate of Gamaliel (cf. Acts 22:3), then when he studied as a scholar of the faith, he would have been heir to the Jewish tradition which suggested that fulfillment of the law included marriage with children. The Talmud, though later than Paul, presented the normal Jewish belief which suggested that a man was merely “half a man” if they never married, indeed, living without God’s blessings upon them because they failed to live up to the duty which God gave to them to be fruitful and multiply.[6] Except for extremely rare exceptions, scholars followed this duty, especially those who studied under and followed those who were among the most exceptional Jewish leaders of their day and age.[7] It would make sense that Paul, with his zeal for the Jewish traditions, would have then established himself fully within the tradition and had a family of his own before looking for and seeking a place of spiritual leadership himself. Nonetheless, when he became Christian, he saw the need for propagation of children was radically altered: the end had come into the world, and so the need for children no longer persisted in the way it did before Christ. Marriage remained a good, but a good for the couple, so to be with each other in love, not for the sake of children (though children would remain a good). Marriage was not rejected, but it no longer was viewed as necessary for someone who had entered into the eschaton by their union with Christ (who himself had no physical children).

It is impossible for us to know whether or not Paul really had a wife. Ancient traditions hint at the possibility. His own words in his letters also hint at that possibility. His own Jewish heritage hints at that possibility. The notion that he was necessarily celibate comes after the radical Christian reinvention of sex and marriage which came after Paul. Paul might have been married or a widower; if he never did marry, it certainly would have been something unusual, and would have set Paul apart in a way which would have had many of his fellow Jews questioning him and his zeal for the Jews.

While the greater, extended Christian tradition suggests Paul was celibate, it is not something which is specifically defined and others in the Christian tradition at least have looked at the question of whether or not he had been married. We would not go wrong in following the greater tradition, and accepting that he probably was celibate. But that means there was something unusual about Paul, even before he became a Christian. Perhaps the apocalyptic sensibility of his age had already radicalized him in relation to marriage even before he was a Christian. Or maybe, however slight the possibility, he had been married and he was what we would have expected of him as someone who promoted himself as following the traditions of the Jews before his conversion to Christ. This possibility is not something which should be outright rejected. Indeed, in an era in which anti-Semitism is on the rise, Christians need to get a greater sense of the Jewish beliefs and traditions from which Christianity emerged, to get a better sense of the way salvation is from the Jews. This appreciation of the Jewishness of the Christian faith by appreciating the Jewishness of its early leaders should alter, then, the way we relate to the Jews. Instead of engaging spiteful hate speech against them, trying to establish a radical divide between Christianity and Judaism, we would begin to be acting like the early Christians themselves, who loved their Jewish brethren and had no desire to separate themselves from them. Paul, as a Christian, remained a Jew with the Jews, seeking always to reconcile the new believers in the God of Abraham with the Jews. This brotherly affection is what Christians need to engage now more than ever. Accepting the greatness of the Jews, those who held the oracles of God, and recognizing how this could have affected the early leaders of the Christian faith is one way this will be possible. This is why there is something appealing to see Paul was married, to see he was truly a man of his people and tradition, and so the notion that he was married should not be something entirely dismissed as contrary to his known character.

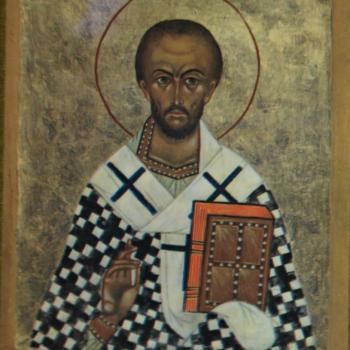

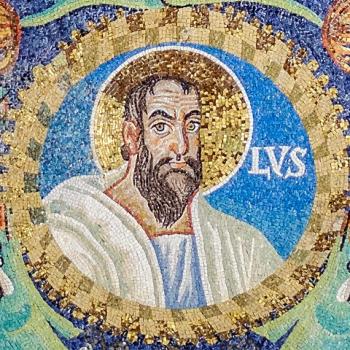

[IMG=Icon of Saint Paul [CC0 Public Domain] via MaxPixel]

[1] Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History in NPNF2(1):161-2.

[2] St Clement of Alexandria, The Stromateis: Books One to Three. Trans. John Ferguson (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1991), 289.

[3] Origen, Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans Books I – 5. Trans. Thomas P. Scheck (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2001), 62. See also ibid., 271.

[4] St. Ignatius of Antioch, “Epistle of Ignatius to the Philadelphians, Longer version” in ANF(1): 81.

[5] St. John Chrysostom, “Homily 13 on Philippians” in NPNF1(13):244.

[6] See The Talmud: Selected Writings. trans. Ben Zion Bokser. Intr. Ben Zion Bokser and Baruch M. Bokser (New York: Paulist Press, 1989), 34-5; 131-3.

[7] Jesus was not constrained by such expectations, for as he often taught, such social constructions were established for the sake of personal glory, something he did not need to seek and so he did not think they applied to him. They might have had their value, but that lay in the spirit and not the mere letter of the law: he himself was to bring about the kingdom of God and bring to it spiritual children, fulfilling the spirit in a way the letter could not.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook