I am a fan and student of the writings of Vladimir Solovyov. His writings contain the foundation for many of my own theological developments, although I take what Solovyov wrote with a critical eye, realizing not everything he said is as useful or invaluable as the core intuition which guided him throughout his career. There are questions and concerns which one can raise with his Sophiological thought, but later Sophiologists like Bulgakov and Florensky have helped deal with those questions and put in check various potential problems that could have flown from a too hasty acceptance of all Solovyov wrote. Solovyov is the founder of modern Sophiology, but it has taken many others to polish out the significance of that Sophiology and to makes sure it remains orthodox in teaching.

One of the great legacies of Solovyov’s Sophiology is the way Solovyov is able to bring together people from different cultural and religious backgrounds and show what they have to offer each other. He provides a way forward not only with ecumenical dialogue between Christians, but inter-religious dialogue that can dare even to engage in comparative theology. He certainly had more interest in the three monotheistic religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, allowing each to present a part of God’s greater plan for the world, but he did not neglect Asiatic traditions such as Hinduism and Buddhism, seeing with them qualities which are also important for the understanding of the history and ongoing development of religious philosophy.

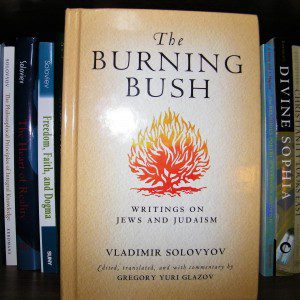

Perhaps no book demonstrates this better than the recent collection of essays, letters and speeches made by Solovyov on the Jews. Solovyov had to deal with fanatical xenophobia which sought to justify not only the persecution of the Jews, but their death. The way anti-Semitism promoted explained itself is very common with modern American anti-Islamic sentiment, and the way Solovyov dealt with such rhetoric will be important to pick up and use in defense not only of Muslims, but any and every foreigner which gets caught in the rise of American nationalistic xenophobia which looks for a scapegoat for the failings of the American people. Therefore, I offer below, this brief review of the book: Vladimir Solovyov. The Burning Bush: Writings on Jews and Judaism. Edited, translated with commentary by Gregory Yuri Glazov (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2016); xviii +609 pages.

In 2008, Vladimir Wozniuk produced a good volume of texts, Freedom, Faith and Dogma, collecting many of Solovyov’s texts on Judaism, highlighting the concerns Christians should have for the just treatment of the Jews, as well as significant explorations on Christian thought, such as his speech, “On the Decline of the Medieval Worldview.” The text gave, to be sure, the most important works Solovyov wrote on the relationship between Christians and the Jews, and other texts helped round up Solovyov’s critical concerns of the history of Christian theology and its misappropriation of Christ’s teaching (which is demonstrated, among other ways, by the way Christians mistreated the Jews).

Gregory Yuri Glazov, godson to Alexander Men’, started his own translation of Solovyov’s writings on the Jews before Wozniuk published his volume, and so the two independently of each other, worked to produce collections of Solovyov’s texts. Nonetheless, there was a difference: Wozniuk brought together the most important of the texts with little extra commentary, while Glazov sought to produce as exhaustive collection as possible, and offer with it, a substantial introduction to the history of Jewish relations within the Russian Empire as well as commentary with Solovyov’s writings. The two projects had different intentions, and both are excellent in relation to the expectation and desire of each of the translator-authors.

In this way, although there texts of Solovyov not found elsewhere, helping make this a useful resource for those who study Solovyov’s thought, the highlight of this volume lies with the exploration of Jewish-Christian relations in Russia (and Europe), with Solovyov serving as a critical lens from the Christian standpoint for the so-called “Jewish Problem” which Solovyov considered was truly the Christian Problem because it was the Christians, not the Jews, who created the problem and failed to live up to their own faith-tradition because of it.

Glazov delineated the problem well in his introduction, as he wrote explaining that there were two issues, one internal with the Jews themselves, but the second, external, and the kind which allowed anti-Semitism to lead to the death camps of Europe:

On the Gentile side, the “problem” resided in the difficulties of integrating the Jews into post-Enlightenment society founded upon the values of liberté, égalité, et fraternité. The difficulty was understood to originate in the nature of Judaism itself because of its own resistance to assimilation. On the Jewish side, following Jewry’s emancipation from the Ghetto, the “problem” pertained to the preservation of Jewish identity in this society. The varying solutions to the problem splintered the Jews of the nineteenth century into Orthodox, Conservative, and Reformed congregations, political parties, and nationalistic movements such as Zionism. The existence of a “Jewish problem” on the Jewish side may allow the phrase to be used in this context without antisemitic connotations. But in Gentile circles, of course, the phrase retains its largely anti-semitic resonance and therefore provided a background, and thereby linguistic impetus, to Nazi attempts to give this “problem” a “final solution” through death camps (22).

Glazov offers an extensive history of the question of Jewish relations with Russian Christians as well as a significant commentary of Solovyov’s works on the Christian problem of Jewish relations, each of which receives their own section before Solovyov’s texts, allowing the unfamiliar reader to understand the context of Solovyov’s works. This truly is what makes the work an important contribution to the history of anti-Semitism, but also, to culture studies, showing how people can be easily worked up with hate speech so that they end up willing to commit great atrocities in the name of security.

Vladimir Solovyov was an independent minded 19th century Russian religious philosopher, who often found himself censored due to his critical remarks of Russian political and ecclesiastical policy. He tried to have his orthodoxy follow with orthopraxis, having them united instead of divided, and this often got him in trouble. It was trouble he was willing to take on for the sake of justice. For example, his rejection of the death penalty, which he famously put forth in a speech in March 1881 asking for the new Tsar to forgo the use of capital punishment for the assassins who killed Tsar Alexander II, cost him greatly, for it served as the end-point of his potential career in academia. He would become an independent scholar, often homeless and broke, moving from place to another, with little of his own, often relying upon the good graces of the friends he had to make sure he survived.

While it was not the full extent of his religious and philosophical thought, certainly his Sophiological understandings helped inspire him in his treatment of non-Christian religions, allowing him to see not only the seeds of Wisdom within their traditions, but also the positive spiritual values contained in them by the grace of God which needed to be affirmed by Christians around the world. This, then, is one of the grounds which he used to justify his high estimation and defense of the Jews, seeing even in their development after Christ a sign of their divine calling and a continuation of the work which God intended from them for Christians to recognize.

Sadly, Christians did not see the goodness of the Jews, and, through all kinds of political intrigue, as well as general xenophobia, Jews throughout the centuries became to be understood in a negative light by Christians. Hate spawned attacks, attacks which Solovyov said no Christian could every justify. Indeed, those Christians who followed through with such unseemly anti-Semitism were seen as the true betrayers of Christ, not the Jews, because they are the ones who claim to follow Christ and yet denounce Christ’s law which told Christians to treat everyone as a neighbor to be loved. When Christians are dived and live in hate, Jews have no reason to believe in Christianity if the Christians do not believe what Christ taught either. “The Jews will not, of course, accept Christianity when Christians themselves reject it; they would doubtfully unite with something which is itself divided” (327).[1]

The texts collected by Glazov not only highlight problem which Christians had to face, that they really did not follow the law of Christ (as exemplified in “Jewry and the Christian Problem”), but also demonstrate his exploration and refutation of many of the lies spread about the Jews in order to encourage a hateful response to them (such as in “The Talmud and Recent Polemical Literature about It in Austria and German,” which offers a thorough debunking of the myths perpetuated against the Talmud) His attempt to not only get the pogroms stopped, but to get respected leaders of his time, like Tolstoy, to work with him in helping the Jews receive just treatment in Russia also find their rightful place in this collection.

While, for those who have not read them, Solovyov’s text are indeed important and should be read with care , what makes this volume invaluable is the introduction on the history of anti-Semitism in Russia and the commentary on Solovyov’s work. This takes the book to another level, and really shows through example the way xenophobia spread and how difficult it is to be refuted on purely intellectual grounds (because it rarely is an intellectual movement, even if intellectuals are often affected by it). We find how Solovyov had to respond to otherwise great men like Dostoevsky when exploring with the relations Christians should have with the Jews.

The Jews were not only scapegoats used to blame for national problems, but it was because they were different, did not “assimilate” to Christian and post-Christian secular standards, but kept to themselves, that xenophobia was able to use them as excuses for national problems. The cry against them can be seen to be the cry used against every stranger by xenophobia: “become just like us, leave, or be exterminated.” This is a cry which should never be made, because it disrupts the very foundations of society, hiding its own demise under the guidance of protecting its own interest.

Gossip and rumors were able to be used effectively (such as blood libel) because the Jews were seen as too different from the rest of society. Such difference was seen as a hostile reaction, and so any and all claims against the Jews were readily believed. “Assimilation” was demanded, and the lack of it was seen as proof of a Jewish conspiracy against the common good. The only way to deal with them was through harsh treatment established by law, and those who rejected such law were considered anarchists who hated law and order.

Certainly we can see similar action and reaction happening today, not with the Jews, but with Middle Easterners in general, making Glazov’s introduction an important reminder of the errors of such thinking, allowing history show how erroneous such ways of thought are.

If the only thing which was published was Glazov’s introduction, it would be a worthy little book for people to read and digest; but when it includes not just the historical introduction, but Solovyov’s essays and commentary on them to help the average reader get the most out of them, this turns out to be a major collection which is a must for those interested in history of inter-religious relations as well as for those concerned about modern forms of xenophobia. Solovyov desired Christians to live up to the teachings of Christ, and rightfully put them to shame for failing to live up to Christ’s teaching for most of history.

While the horrors of the extermination camps for the Jews are, for now, in the past, Christians have yet to learn the lesson of the past; a new rise of nationalistic ideology tinted by the lens of xenophobia is taking over supposed Christian leaders. Now is the time to put a stop to it, and reading the warnings of the past is one way to see how things can turn out and reinforce why we must put a stop to it now before it is too late.

I cannot recommend this book enough. It deserves a full 10/10 for what Glazov has been able to put together for a book which I fear foreshadows the conflicts which might be coming in modern America.

[1] From “Jewry and the Christian Question.”

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook:

A Little Bit of Nothing