- Trending:

- Pope Francis

- |

- Resurrection

- |

- Trump

- |

- Social Justice

- |

- Peace

- |

- Love

The 100 Most Holy Places On Earth

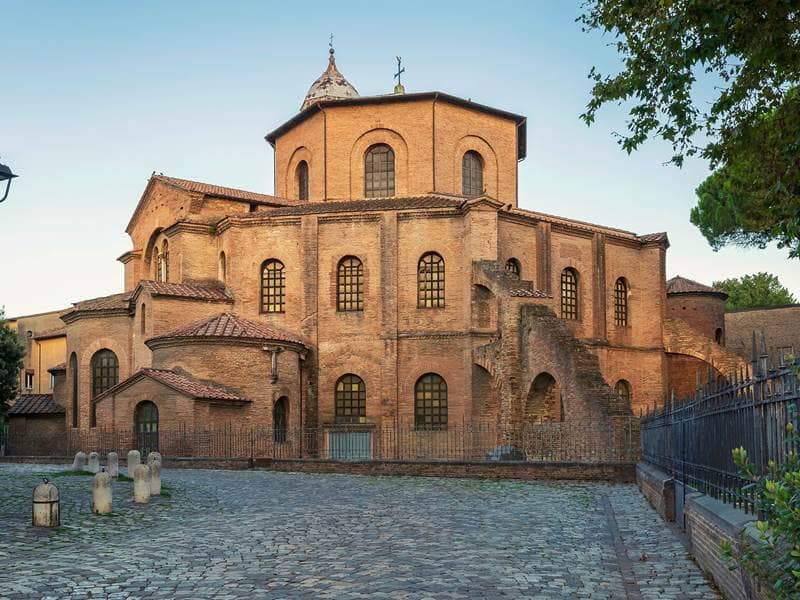

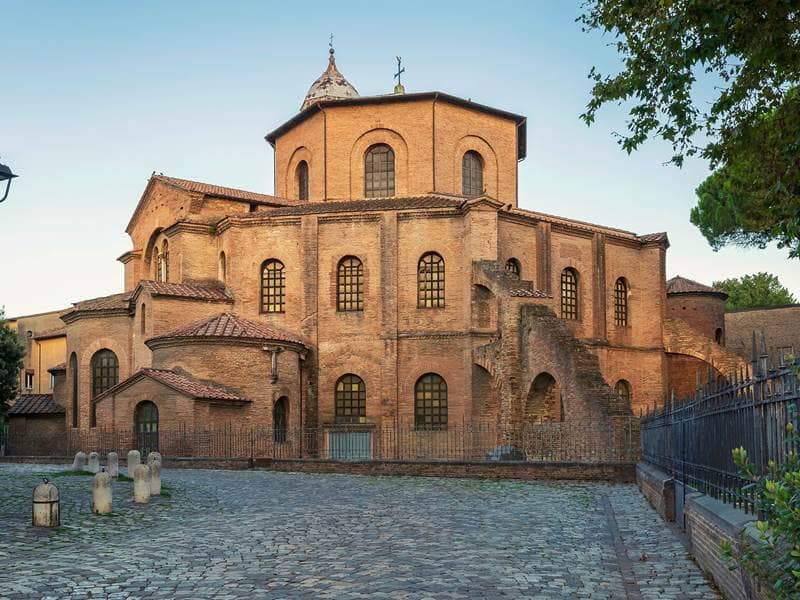

Basilica of San Vitale

Associated Faiths:

Roman Catholicism

Also frequented by Christians of other High and Low-Church traditions, as well as tourists of other religious traditions.

Accessibility:

Open to visitors.

Annual Visitors: 2,000,000

History

This 6th century church—formally granted the honorific title of “basilica” because of its ecclesiastical and historic significance—is an important representation of early Byzantine exterior architecture and interior art. It is illustrative of that which was common in late antiquity (i.e., 3rd-7th centuries AD). That being said, it does also incorporate certain Roman elements in its architecture—such as the frescoes (in the interior dome) which date from the late 18th century. This is the only major church, dating from the reign of Emperor Justinian I, to survive essentially intact.

During the first half of the 5th century, Ravenna was effectively the center of the Western portion of Christianity. Thus, having a prominent church, such as San Vitale, became important. Bishop Ecclesius (or Ecclesio) of Ravenna ordered the construction of the building, which began in AD 526 and was completed in 547. The speed at which this church was erected is an impressive feat for that era. Both this basilica and the one in nearby Classe (known as the Basilica of Sant' Apollinare) were largely funded by a local banker and architect named Julius Argentarius. Some art historians believe that Julius’ portrait appears as one of the courtiers in the Justinian mosaic of San Vitale (since “donor portraits” were common in that era).

According to tradition, the church was built on this specific site because it was the location of the martyrdom of Saint Vitalis of Milan—who came to Revena, where it was discovered that he was a Christian. Thus, he was tortured on the rack, and then thrown into a pit where he was buried alive by stones and dirt. (Some confuse the Saint Vitalis, for which this church is named, with another Saint Vitalis who was martyred in Bologna circa AD 304—though it is the former, not the latter, who is the namesake of this “basilica”).

One of the things that draws so many visitors to this site each year is the church’s incredible Byzantine mosaics. San Vitale contains the largest anthology of well-preserved Byzantine mosaics in the world (with Istanbul, Turkey being the one exception). The theological and political significance of these iconographic representations are nearly unparalleled. And while some have been damaged and repaired, nonetheless, what remains is exemplary of the era. They preserve, in art, an understanding of the political views of the time, as well as the theological conceptions of the era.

Religious Significance

Saint Vitalis is the patron saint of Ravenna, Italy. In addition, a “Saint Vitalis” is the patron of the municipality of Granarolo dell ’Emillia (in Bologna) and of the city of Thibodaux, Louisiana. (Not all agree that the same Vitalis is the patron of all three places.) According to tradition, the Saint Vitalis of Revena was a Christian martyr who gave his life for the faith—though it is uncertain if he was put to death under Nero (AD 54-68) or Marcus Aurelius (AD 161-180).

Aside from the remarkable fact that this building has survived largely intact, its murals are its most important feature. A significant portion of the walls being covered with symbolic depictions, they were designed not simply to portray scenes from the Bible, but also to establish the authority of the emperor in the Church and in God’s plan for the history of the world. This is a view that would have been important and influential at that time in Christian history, when emperors (such as Constantine and Justinian) saw themselves as “defenders of the faith.” As evidence of Justinian’s feeling that he had a special and divine role to play in God’s plan, he is depicted with not just a crown on his head and a purple imperial robe over his shoulder, but also with a halo. As the foremost figure in his mural—even overlapping the Bishop to some degree—he is depicted carrying the Eucharistic basket, and being flanked by priests and soldiers (who bear the Chi-Rho on their shields). In the mural, Emperor Justinian stands as a sort of “vice-regent” or “emissary” of Christ on the earth—or so he would have worshipers in the church perceive him.

The apse has Jesus Christ, angels, and Saint Vitale at its center. Jesus appears to be offering the martyr’s crown to Vitale, suggesting both his saintly status, and also Christ’s acceptance of his offering (in the form of laying down his life for his witness of Christ and His Church). Elsewhere in the murals, we see depicted Bethlehem and Jerusalem—symbolic of Jesus’ divine birth and redeeming death. While some have seen pagan meanings in the two angels holding what has been called the “blazing white sun,” others note that the Bible associates the sun not with emperors and pharaohs but with Christ, the Son of God. The presence of the Greek letter alpha at the center of the sun has also been interpreted as a symbolic representation of Christ, rather that Justinian (or some other emperor).

The octagonal shape of the church is symbolic of a number of Christian motifs, including baptism, rebirth, resurrection, preservation, and Jesus Christ Himself (who was often associated in antiquity with the number 888). Thus, in many aspects of this building, one is reminded of Christ and His work of redemption and resurrection on behalf of the faithful follower. Even if Justinian placed a great deal of emphasis on himself in the art displayed in the building, the Christocentric and biblical symbols throughout trump any Justinian focus, at least for the attentive viewer.

Pilgrims who visit this sacred site, which has been marked as the location of the martyrdom of one of Christianity’s early Saints, are provided with a visually stimulating experience like none other. The murals, combined with the Byzantine architecture (of late antiquity) make this an important pilgrimage site for Catholics and non-Catholics alike. Being the place of martyrdom, it is also an important site for memorializing the early centuries of Christianity, when so many suffered and died for their witness of the faith. Thus, the Basilica of San Vitale stands as an invitation to practicing Christians to live their lives for the God they profess to worship—and to believe that such sacrifices will produce beauty, much as Saint Vitalis’ martyrdom resulted in the production of this incomprehensibly beautiful “sacred site.”