When I was in college I had the opportunity to spend a year in Oxford, dwelling amidst centuries-old buildings that housed many ghosts of ages past. I was able to take some time to tour Europe and visit museums, cathedrals, city squares, and monuments that breathed the rarefied air of antiquity. Symbols of culture, these, and they elicited from my young mind images of figures whose writings, paintings, sculptures, and music chronicled the history of an entire civilization.

I, a young man from the suburbs of Chicago, found myself feeling small amidst the sweep of this vast three millennia-long project that has come in academic circles to be known simply as "the West." Trained by the Jesuits and immersed in a program of study of the Western Cultural Tradition -- a program in which I myself am now a professor -- I felt a sense of the transcendent, a sense that my own strivings toward a good life were but a small note in a grand symphony.

That feeling of smallness is something I hope to cultivate in my students, for it is that sense of participating in a larger story that is, I believe, a prerequisite for citizenship not only in the West, but indeed the global community. It's easy to lose sight of that larger story in a world of blogs and tweets -- the fast pace of the information age demands constant attention to the now at the expense of the always. "Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?" T.S. Eliot asked famously in his modernist poem "Choruses from the Rock."

The criticism of the larger story comes from those who have not been (sufficiently) part of it -- women, non-Western or native peoples, the economically disadvantaged, and so on. They are right to say that all this grand language of "tradition" and "culture" can sometimes be used as a hammer, to pound away at a political scheme orchestrated by an elite. In the United States, especially, there's an iconoclastic strain: "We're not royals here, nor are we papists or aristocrats. Take your culture and leave me my freedom." "Culture" smacks of dusty old ways and people with starched collars and no life. Freedom is about dancing to your own drumbeat.

The notion of culture itself is at a crossroads. For if culture -- like its cognate word "cultivate" -- is about a certain way of growing, then the obvious questions are about who's doing the sowing, what the seeds are, and what's going to be harvested from them. What's the point of culture? And how is it different from any number of historical attempts to control people, like the absurd Chinese operas that emerged during the horror of the Cultural Revolution, inculcating revolutionary propaganda? (See the fine film Mao's Last Dancer for one dancer's story of escaping from that reality.)

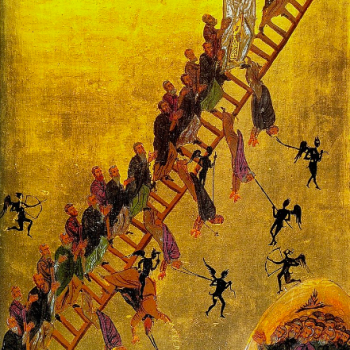

This column proposes that culture is the ongoing conversation of peoples reaching for the transcendent: questions like "what changes, and what remains the same?" and "how shall we live?" -- the kinds of questions, in short, that we raise today much like our ancestors of three millennia past, and whose answers, far from being irrelevant and arcane, are as challenging to us today as they were when they were first written.

A couple of days ago I saw the truth of that proposal. The scene was a seminar table of fifteen first-year students; the text was Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics. It was a text I had read when I sat in their place, and now it was my turn to lead the discussion. Our topics: happiness; character; the good life. These students understood the stakes in this discussion. And knowing them as I do, I could see that for many the discussion was far from abstract intellectual gymnastics. They want to know how to live, and they are fascinated by the idea that a 2,300 year-old text might help them do it.

Culture is important because it preserves the conversation, not unlike a good host at a cocktail party. The guests come and go, but the conversation progresses because new guests hear the accumulated insights of those who have gone before. Of course, the challenge of the host is to truly welcome the new guests, and not to wall off the conversation out of some sort of elitism. Yes, the host has power -- this is undeniable -- and at times the "hosts," the cultural elites (the aristocracy, the Church, or both) have treated the conversation as a kind of private party. The shouts of liberté, égalité, fraternité! have busted down the doors, often for good reason.

Today, the new challenge is to discern the elements of culture that help us to deepen the long conversation. It would be a great loss to reinvent the wheel of culture -- to allow the turmoil of the last century to divorce us from the great insights of the past. For it is precisely because of these insights that we can invite others into this conversation, for it is ultimately about shaping a global community. T.S. Eliot again: