By Elijah Davidson

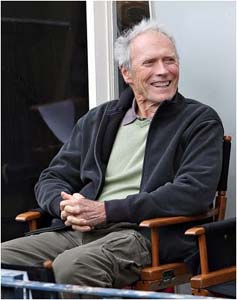

I've never walked out of a theater before a movie was over, but one time I came very close. The film was Clint Eastwood's Million Dollar Baby, and I so disagreed with the message of the film, I almost abandoned it with about five minutes left.

I've never walked out of a theater before a movie was over, but one time I came very close. The film was Clint Eastwood's Million Dollar Baby, and I so disagreed with the message of the film, I almost abandoned it with about five minutes left.

If you've seen the film, you know it deals in part with euthanasia, but this wasn't the part that disturbed me. I reacted strongly against the film's overwhelming lack of hope. I stayed through the end of the film, because I didn't want anyone to tell me I couldn't critique it because I hadn't seen it all.

The film stuck with me though, and I knew I had to watch it again to figure out exactly what I rejected in it. I've since watched it many, many times, and though I still disagree with its seeming declaration that there is no reason for hope, I celebrate the quality of the film, and, in part, its honest view of the world.

And Clint Eastwood has become a director whose films I anticipate. He is a director who has consistently crafted quality films. Some call him a classical director because he makes serious movies in a very conventional style. His films are not flashy or flighty. They are as mature and thoughtful as the man himself.

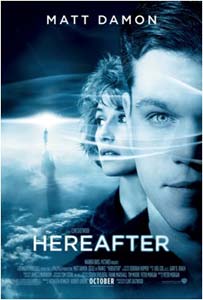

Hereafter is no exception. In fact, it is an exceptional example of what makes Clint Eastwood's films fine.

Hereafter is no exception. In fact, it is an exceptional example of what makes Clint Eastwood's films fine.

The movie follows three people who have been profoundly affected by death. One is nearly lost in a tsunami, one can supposedly communicate with the dead, and the third loses a loved one tragically. These three lives eventually intersect, but for most of the film, they are separate as the film uses their stories to explore what, if anything, awaits us beyond this life.

Hereafter pulls no punches. It is a seriously tragic film, delving deeper into the desperation of the bereaved than most other films. It also rejects religious and spiritual explanations of life after death, siding instead on the mysteriousness of the beyond. The film doesn't reject the idea of an experience on the other side of death, but it does reject any easy explanation of what that experience might be.

It is also a profoundly compassionate film. Hereafter takes grief and loss seriously. It affirms the universality of death and the pain it inflicts upon humanity, and it encourages us to love and care for one another.

Hereafter is the most difficult kind of film for me to watch. On the one hand, it is finely crafted. I can't help but be swept away by the narrative and appreciate the skill of those involved with the film's production. On the other hand, the film explicitly rejects my faith. There is a scene in the film where a character watches videos online of various religions explaining their take on life after death. This scene ends with the character shaking his head "no" as the name of Christ still echoes in the theater.

I am saddened that the film so completely rejects the hope that I have while at the same time practically crying out for hope of some kind.

I am saddened that the film so completely rejects the hope that I have while at the same time practically crying out for hope of some kind.

It would be easy to reject this film because it essentially rejects me. It sets itself up as my enemy. Instead, I must do the hard work of loving this film and by extension, the people involved in its production and the people in my life who resonate strongly with Hereafter.

In the absence of hope, Hereafter encourages its audience to care for one another. I can get behind that. I don't believe that we are all we have, but I do believe that we do indeed have one another.

Because he challenges me, because he consistently makes good films, and because he is unflinchingly honest, Clint Eastwood is perhaps my favorite filmmaker. I would love to sit down with him for lunch and an off-the-record conversation. We think very differently. We believe very differently. But hopefully, I love the world, broken as it may be, as much as he does.

Elijah Davidson is Co-Director of Reel Spirituality. More reflections like this one can be found at www.reelspirituality.com.

10/29/2010 4:00:00 AM