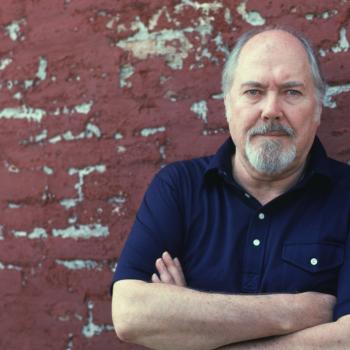

By M. Norbert Kilmer

In LDS culture, serving a mission at one's own expense and often in a foreign language and country is a lengthy rite of passage. At the age when most people are going to college and joining frats, missionaries live a semi-independent but rigid life of preaching, teaching, and study. Personal growth most often occurs when faced with struggle, and missions provide plenty of that, in physical, social, spiritual, and intellectual ways. Here M. Norbert Kilmer reflects on his mission experiences in Europe and how he came to own them.

On 4 January 1989, I entered the MTC as a missionary, headed for the Netherlands Amsterdam mission. Following a grand tradition, I thought I would reflect for a moment on that experience.

On 4 January 1989, I entered the MTC as a missionary, headed for the Netherlands Amsterdam mission. Following a grand tradition, I thought I would reflect for a moment on that experience.

In the autumn of 1988, I wasn't sure I wanted to go on a mission, so I took the BYU religion class Sharing the Gospel. Spencer Condie was the teacher, a sociology professor recently returned from being a mission president in Austria. The class was inspiring and uplifting, but I still wasn't sure. I had my papers all ready, and I went to see him.

I asked, "If missionaries are just supposed to be obedient and do what they're told to do, why does it matter if I go on a mission? I'm going to struggle to be the person they want me to be. Wouldn't it be easier for someone else to be sent out who can be that missionary-person with less struggle?"

He said, ‘"The Lord doesn't want robots. He wants you, with your strengths and your insights. The missionary force needs all kinds of people, and it needs creative, thoughtful, intelligent young men like you." I prayerfully considered this and sent in my papers.

A year into my mission, Elder Condie of the Quorum of the 70 toured our mission. At the zone conference, he recognized me and wanted to have a chat, and I was pleased to meet with him. He asked how the mission was going. I said, with all due respect for him, "This is not the mission you described."

For most of my mission, my worst fears were realized. The predominant doctrine was obedience, and the leadership style and reporting systems of the mission seemed designed to maintain the highest level of obedience and minimize individuality, innovation, or even spiritual insight. We were to do as we were told, and if we did we would be blessed; if we wavered in our faith in the mission rules and programs, we had weak testimonies and were not worthy of the Holy Ghost. No element of the missionary program -- the commitment pattern, the three weeks to baptism path, the presentation of the discussions, or the heavily prescribed goals for how we spent our time -- could be questioned or modified to best serve individuals or communities: such ideas were met with hostile accusations of weak faith and even heresy.

I responded to this environment with frustration, anxiety, and some rebellion. I was told I was a bad missionary by mission leadership, both implicitly and explicitly, and, despite the fact that I was involved in the teaching and baptism of more converts than the average missionary, I believed them. At the end of my mission, I felt no positive connection to the structure of the mission or the leaders. I recognized that I had had some positive experiences, some of them spiritual, but they were in spite of the formal mission and its programs and rules, not because of them. I regarded it as a negative episode of my life and walked away.

In my twenties, my mission experience became symbolic of my attitude toward the church more generally. I saw the church as a hierarchy that attempted to dictate spirituality rather than encourage the individual growth and inspiration of the members. The environment of BYU in the early 1990s helped solidify that view, and in the same way that I put my mission behind me, I was happy to put the church behind me.

And then, several years later, I found the packet of letters I had sent home to my parents during my mission. I expected them to be filled with bitterness and frustration, and they were. But I also found a lot of joy: exposure to unfamiliar languages and cultures; excitement about working with investigators; opportunities for service; friendships with companions, members and non-members. I dug out my missionary journals, which I had purposely put away after I got home, and found the same thing. Again, a fair number of these experiences were outside the approval of the official mission, but there they were.

It was my mission. All in all, it had been good. I had allowed the mission leadership, flawed for reasons I never understood, to take that away from me. I started thinking about my mission more, looking at what I had learned from it and how it had shaped my life, reconnecting or strengthening connections to the people I had met there.