By Gary Gach

Kobayashi Issa once noted in a haiku how in our coming into this world, in our leaving, and in between, we seem to go from one bath to another. Since time immemorial, human beings have observed such passages with ritual. Indeed, the recurrence of important life events from generation to generation is at the wellspring of our feelings for the sacredness of life. Out of such stuff do religious paths shape human community, find harmony with nature, and point to our connection to divinity. Buddhism is no different. In this brief article, we will explore some aspects of Buddhist rites of passage into adulthood. In future postings, we intend to explore Buddhist responses to other life events -- love and death, for instance.

Kobayashi Issa once noted in a haiku how in our coming into this world, in our leaving, and in between, we seem to go from one bath to another. Since time immemorial, human beings have observed such passages with ritual. Indeed, the recurrence of important life events from generation to generation is at the wellspring of our feelings for the sacredness of life. Out of such stuff do religious paths shape human community, find harmony with nature, and point to our connection to divinity. Buddhism is no different. In this brief article, we will explore some aspects of Buddhist rites of passage into adulthood. In future postings, we intend to explore Buddhist responses to other life events -- love and death, for instance.

Roots and branches

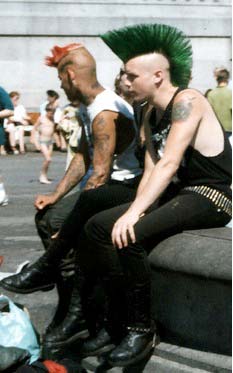

Our ancestors knew the importance of interweaving the lives of their young, especially the boys, into the life of the community. At a certain age, a boy's body experiences a fury of maturation. He suddenly gets pumped full of hormones roaring through his metabolism like a roaring white-water river careening over unchartered falls. He tries to call out and hears his voice break, cracking open, to reveal a deeper voice. He's thrust as well into sexuality. It's all beyond him, uncontrollable.

Our ancestors understood. Wise elders of the tribe knew the young boys, on approaching manhood, were gripped by outrageous demands, of both flesh and of imagination, and could kill the entire tribe in their sleep. They evolved rites of passage to guide the boys into manhood, initiating them into an ancestral vision of relationship with the universe, as interdependent beings, standing on their own two feet, as members of a tribe itself part of a greater kinship of being.

Today, our young men are killing themselves as well as the community, as inner cities are staked out by gangs in growing networks of escalating violence, tit for tat; and with teen suicide an alarming epidemic claiming almost as many lives as accidents in cars; plus the loner students coming to school one morning dressed in black, in mourning for themselves, armed and over the top, wasting everyone in sight: in each tragedy, each victim mourned by family, friends, the community, a widening chain reaction.

American culture, being secular, provides rites of passage for males in the form of military service, college, or the criminal system. Thailand, on the other hand, is a Buddhist nation, where a maturing boy is ordained as a monk. After such initiation, he's free to then "disrobe," to leave the monastery and return to the life of the householder.

Yet America has deeper Buddhist roots than might be obvious to the casual passerby. The first practitioners of Buddhism in America, over a century ago, were Chinese and Japanese immigrants. These representatives of "Pure Land" schools constitute not only the largest groups in Asia and America, but their traditions here are thus the oldest, encompassing many generations. Traditions from the homeland have been brought over, such as "Sunday school" and "Buddhist youth league," which provide full rites of passage. (That these traditions have not yet shared their experiences with nonmembers speaks to separate issues, as of the Japanese-American experience during WW II, for example.)

In contrast to Chinese American and Japanese American Buddhists enjoying eighth- or ninth-generation traditions, for many European Americans, Buddhism is quite new. Some communities do not last more than a generation or two. Relatively recently, many Euro American Buddhists have experienced parenthood. In so doing, they are evolving rites of passage within their new Buddhist communities.

Whether new at the game, or participating in a venerable tradition, for all participants in rites of passage, young and old alike, it's a learning experience. Zen priest Norman Fischer writes eloquently of this in Taking Our Places: The Buddhist Path to Truly Growing Up, his memoir of establishing a coming-of-age study group at Zen Center. Of note is how central to maturity he finds the quality of trust.

A person who chooses to walk the path of maturity is a trusting and trustworthy person. He or she has learned, through clear observation over time, that there is no alternative to trusting what is, for to mistrust what is, is to reject our life experience, which is all we've got to build on, no matter hard it may be. To take our places in this world we need to trust the world, ourselves, and each other this much.