By Hussein Rashid

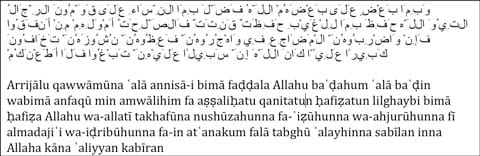

God commands Muslims to beat their wives. At least, that's how many Islamophobes would describe verse 4:34 of the Qur'an. As we all know the verse states:

The point being that just as neither Prophet Moses nor Prophet Jesus spoke English, neither did Prophet Muhammad. The Qur'an is revealed in Arabic, so when someone says the Qur'an says something, and then quotes only the English, what he is saying is that he has chosen an interpretation of the Qur'an that fits his argument.

The point being that just as neither Prophet Moses nor Prophet Jesus spoke English, neither did Prophet Muhammad. The Qur'an is revealed in Arabic, so when someone says the Qur'an says something, and then quotes only the English, what he is saying is that he has chosen an interpretation of the Qur'an that fits his argument.

In 2008, Dr. Laleh Bakhtiar published a highly-heralded translation of the Qur'an called The Sublime Qur'an, partially in response to this verse. Her basic argument is many of the English translations suggest that the verb in the verse, "iḍribū," from the root "ḍ-r-b," is some version of "hit." She makes two critiques of this translation:

- It contradicts another verse of the Qur'an where a wife is not to be mistreated by her husband.

- The Prophet Muhammad, the example of the perfect Muslim, never hit any of his wives.

Her belief is that the verse is mistranslated, and does not in fact reflect traditional Muslim understandings of the verse. Her translation says:

Men are supporters of wives because God has given some of them an advantage over others and because they spend of their wealth. So the ones who are in accord with morality are the ones who are morally obligated, the ones who guard the unseen of what God has kept safe. But those whose resistance you fear, then admonish them and abandon them in their sleeping place then go away from them; and the they obey you, sure look not for any against them; truly God is Lofty, Great.

The root "ḍ-r-b" has the same semantic range as the English word "strike." In the same way one "strikes a tune," "strikes a drum," or "strikes oil," the words are very strong and visceral, but not necessarily physical. To me, the best approximation that keeps the physicality of the word, while indicating its true meaning, is "sever," as in "sever a relationship." The basic sequence of event, for couples in conflict, is to argue, to separate, and then to divorce.

Many pre-modern translations of the Qur'an seem to support this reading, as early Persian and Urdu translations do not use the words for "hitting" (zadan/maarnaa), but "breaking" (keshidan/tornaa). In Qur'an and Woman: Rereading the Sacred Text from a Woman's Perspective, Dr. Amina Wadud highlights the processes by which patriarchal understandings are grafted onto the text, in ways not dissimilar to other faith traditions.

As with any religious scripture, we have to keep two things in mind:

- The Word of God can never be truly understood by mortal creation, except by Divine Guidance.

- Any act of translation is inherently an act of interpretation.

I do not deny that there are many problematic readings of the Qur'an, but no normal human should be able claim the definitive understanding of what God says, least of all through translation -- someone else's interpretation -- or without understanding how Muslims themselves understand the text. Just as no one would take me seriously as a Muslim, academically trained in the study of Islam, if I were to start explaining Catholic theology, no one should take armchair experts on Islam seriously. Dr. Carl Ernst, in his book Following Muhammad, says:

But the focus of many modern Protestant denominations on the Bible has led to the expectation that one can understand everything of importance of the other religious traditions if one knows what is said in their scriptures. This concept of scripturalism is tempting, but it is a fallacy. It assumes that all scriptural verses are equally weighty, that there is no debate about their meaning, and that there has been no change over the centuries in the understanding of particular verses. It also assumes that every member of a particular religious group is equally certain to follow every prescription found in the holy book (or books). Can one predict the behavior of a Christian simply by taking a verse out of the Bible and assuming that it has a controlling influence over that person? (pg. 55)

The interpretive methodologies of one faith tradition does not carry over to other faith traditions. However, there seems to be an understanding that we can understand another's faith by putting it into terms we understand. Of course, that way can be rich to start a conversation, but will not lead to any real understanding unless we engage in dialogue. We need to understand that every faith has its own way of understanding itself and how to interpret scripture. Projecting our own anxieties, perhaps issues we are not willing to engage with in our own faith, onto others achieves nothing.