By Mark Shaw

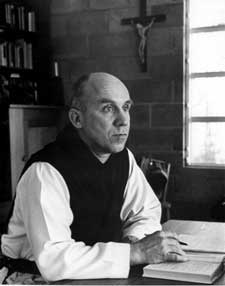

In my first article on Thomas Merton, I noted that the famous monk questioned whether he was truly a converted Christian, providing a steppingstone for examining exactly what is meant by the term "conversion" and how it applies to religious seekers both Protestant and Catholic. To understand Merton's struggle to discover who he really was - a devout Christian or one hiding behind a mask as a Christian "wannabe" - it is necessary to read his own words about the subject. In this excerpt from my new book Beneath the Mask of Holiness: Thomas Merton and the Forbidden Love Affair that Set Him Free, we learn more of Merton's thoughts, portraying a man who knew he was confused and in need of spiritual direction.

In my first article on Thomas Merton, I noted that the famous monk questioned whether he was truly a converted Christian, providing a steppingstone for examining exactly what is meant by the term "conversion" and how it applies to religious seekers both Protestant and Catholic. To understand Merton's struggle to discover who he really was - a devout Christian or one hiding behind a mask as a Christian "wannabe" - it is necessary to read his own words about the subject. In this excerpt from my new book Beneath the Mask of Holiness: Thomas Merton and the Forbidden Love Affair that Set Him Free, we learn more of Merton's thoughts, portraying a man who knew he was confused and in need of spiritual direction.

Book Excerpt:

Thomas Merton's personal correspondence with theologian and friend Rosemary Radford Ruether in 1966-67 is important to understand how Merton truly was in crisis and [whether he would choose Margie Smith or God] . He respected Ruether's opinions because "she is very Barthian-which is why I trust her. There is a fundamental honesty about her theology." Ruether joins Dr. Gregory Zilboorg as the only ones who appeared to see beneath the mask of holiness Merton wore, morning to night, as he suffered within.

In late March 1967, after hearing from Merton about various aspects of his life, Ruether told him of her disappointment in him due to his defensiveness and his constant need for "proving, proving how good your life is, etc." She chastised him for not listening to her about balancing his life and for his inclination to distort her words with reactive responses lacking sufficient thought. A follow-up paragraph was even more direct, with Ruether telling Merton he was in crisis, but fighting it with lengthy arguments. She admitted catching only a glimmer of what was bothering him, but believed the depths of his troubled soul were not monastically related, but based on the "rhythm of your personal development." She told him he needed a new point of view and if he didn't find one, if his inner turmoil was not addressed properly, "it will surely mean a regression to a less full existence for you, while if its meaning is properly discerned, it will be a new kairos leading to a new level of perception."

Ruether's insights into Merton's state of mind included her observation that his subconscious needed a change of attitude while the "super conscious. . . [was] fighting it off." This was causing, she believed, a defensive posture toward his monastic life whenever the topic turned to his present mental condition. Merton responded by telling his friend, "You are perhaps more right than I think about the ‘crisis,' though I have the impression I am not in much more of a crisis than I have been for the last ten years or more." This frank admission of being in crisis well back into the 1950s was telling, but even earlier, during the late 1940s, he acknowledged his conversion was not complete, that it was continuing and that it was something occurring over a whole lifetime with alternating peaks and valleys.

Join the discussion: What is your experience of religious conversion?

Predictably, Merton saw conversion as an open-ended journey, "an on-going development," and "a dynamic thrust forward and upward." He liked the metaphor of a journey. Merton scholar Anthony Padovano agrees, believing Merton experienced "many transformations" and "many conversions," ultimately "accepting one transformation after another." Merton explained his own definition of being a Christian on many occasions. He called it a "way of life, rather than a way of thought" and decided one could only "understand the full meaning of the Christian message" by living the Christian life. He further concluded that being a Christian meant being holy, and such was possible only if one was free from "the tyranny and the demands of sin, of lust, of anger, of pride, ambition, injustice, and the spirit of violence." When the person renounced sin and selfish living, peace and serenity resulted, because God lives and acts within. Being truly holy was not easy, he suggested, and possible through willpower or good intentions. Only through a difficult struggle could a person recognize the limitations and weaknesses infesting them. Trusting in God and imitating Jesus, wrote Merton, were the keys to receiving "mysterious strength that has no human source."