Editor's Note: Below is a "Monday Sermon," from our series of sermons at the Patheos Preachers Channel that pastors can enjoy and learn from. It is our hope that this particular series from Daniel Harrell, which preaches through the Church Fathers, will encourage pastors, show them a way of approaching theological education from the pulpit, and refresh their theological memories. See Reverend Harrell's columnist page for more information.

If existentialism is that philosophical theory which emphasizes the existence of the individual as a free and responsible agent acting in accordance with their own determination, then my existentialist act during my first visit to the Minnesota State Fair was to freely eat fried cheese curds, a corn dog, caramel popcorn, Tom's Tiny Donuts, Sweet Sarah's Chocolate Chip Cookies, and then chase it all down with a high dose of hot sauce on a Jamaican jerk chicken pastry—on a stick. Had I been a younger man all of this would have been followed by a trip to the midway for a ride on the vertigo-inducing, gastro-upheaving Zipper. Instead I rode the Ferris Wheel.

My mention of existentialism is due to my foray into the life of Søren Kierkegaard, the ascribed father of Christian existentialism. After detecting how too many fellow philosophers tried to make the Christian life easier, Kierkegaard subsequently dedicated himself to making it harder (which he did in part by publishing only in Danish). Focusing as he can on the despair of failure, I pull out Kierkegaard whenever I'm having a bad day—just to make sure I milk it for everything it's worth.

Kierkegaard was born in 1813 into a strict Lutheran home, which may explain a lot. He studied ten years to become a minister, but never made it into the pulpit due to an intense and nagging sense of uncertainty and melancholy that drove his entire career. "Where am I? Who am I? How did I come to be here? What is this thing called the world? How did I come into the world? Why was I not consulted? And If I am compelled to take part in it, where is the director? I want to see him." Kierkegaard's uncertainty did not prevent him from falling in love, but it did keep him from tying the knot. He fell head over heels for a woman named Regine Olsen, but soon broke off their engagement once his doubts got the better of him. This decision haunted him for the rest of his life—thankfully, since so much of his output derived from the despair he experienced over abandoning true love. His first book was a justification of the break-up, entitled Either/Or, which set forth the basic tenet of his philosophy: everybody has to make choices among the options present before them. "I see it all perfectly; there are two possible situations—one can either do this or that. My honest opinion and my friendly advice is this: do it or do not do it—you will regret both." "Our life can only be understood backward, but it has to be lived forward."

In contrast to the reigning emphasis on "idealism" in his day, Kierkegaard stressed existence, which he argued to be real, painful, and more important than any idea. "Listen to the cry of a woman in labor at the hour of giving birth," he wrote, "look at the dying man's struggle at his last extremity, and then tell me whether something that begins and ends thus could be intended" as ideal. Though disposed toward despair, Kierkegaard nevertheless saw the hard reality of life as an invitation to faith. Faith for Kierkegaard was based on neither doctrinal conviction nor positive feelings, but on a passionate commitment to Christ in the face of uncertainty; a risk of belief that demands denial of self.

Such self-denial brings us to mind climactic verses from Mark's gospel—a baseline for Kierkegaardian faith. Jesus asks, "Who do you say that I am?" Your answer invites a commitment but to commit demands that you do something about it. "It is so hard to believe," Kierkegaard said, "because it is so hard to obey."

In Mark 8, the ever-impulsive apostle Simon Peter identifies Jesus as the Christ, which in Matthew's gospel made the crowd go wild. Delighted, Jesus renamed Simon "the Rock" and gave him the keys to heaven. But here in Mark, Jesus tells Peter to keep quiet, concerned, on the one hand, that people's Messianic ideals would derail the necessary realities of his mission. On the other hand, tradition holds that Mark was Peter's right hand man. Maybe Peter insisted that Mark leave out Jesus' congratulatory remarks given how bad Peter's own idealizations were going to mess things up in the next few verses.

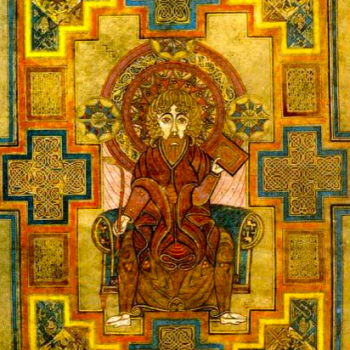

Peter finally realizes Jesus as Christ the King, only to have Jesus specify how being king meant being crowned with thorns and strung up to die. Such news did not sit well. It would be like a franchise quarterback announcing that he let the opposing team run up the score. Or like the candidate you supported pushing the opposing party's legislation instead. Or like the acclaimed war hero giving up without a fight. How can Israel be saved if its Savior surrenders? Peter pulls Jesus aside to straighten him out. He tells him to knock off the death talk. He's scaring the other disciples—this despite Jesus saying that he would "rise again in three days." Not that it mattered. Real messiahs don't rise from the dead—real messiahs don't die in the first place.