Karl Giberson is no stranger to controversy. Though, if you choose to write to and for evangelicals in defense of science, you'd have to expect as much. As a scientist himself, and a firm believer that evolution doesn't contradict scripture, Giberson has become a hero for likeminded evangelicals. His work with Francis Collins in establishing BioLogos has gone far to institutionalize these views.

And yet, if you're on the other side, if you're a strict biblical literalist and a young earth creationist, Giberson and his views are a constant thorn in your side. In his various teaching positions—at Eastern Nazarene College for over twenty-five years, at Gordon College, and most recently at Stonehill College—and with the publication of each of his nine books, controversy has followed him.

This was perfectly illustrated in a recent Facebook post on the page of a group called "Concerned Nazarenes." A commenter on that page wrote of Giberson, "I am thankful he has left ENC, because he has spent years there poisoning the minds of many youth. He will have much to answer to the Lord unless he repents."

When Giberson reposted this note on his own Facebook page, it garnered over seventy-five responses in less than 24 hours from friends and fellow faculty, but mostly from students, thanking him for "poisoning" their minds.

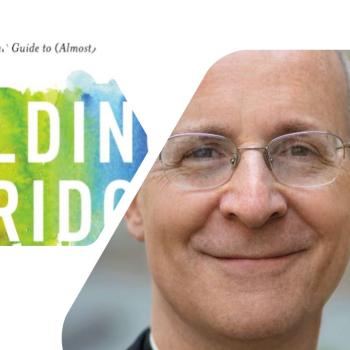

Recently, I had the opportunity to sit down with Giberson in the student center at Eastern Nazarene (where I began teaching after he left to pursue other opportunities) to talk about his latest book, Seven Glorious Days.

Tell me a bit of the story of this book. I understand it was initially planned as part of your book with Francis Collins.

The idea of the book is something that I always wanted to do. Many scholars feel that the way you have to look at Genesis is to keep apart the theology and the primitive science that's there. And the unwillingness of fundamentalists to do that simple hermeneutic exercise is what gives rise to the evangelical rejection of so much modern science.

So, at the very end of the book with Collins [The Language of Science and Faith: Straight Answers to Genuine Questions] I thought, let me do a simple creative exercise in which I take Genesis and transform the text into what I think it would look like if it was written today.

The exercise worked and I sent it to some scholars and everyone liked it. But in the final editorial stages of the process, my editor expressed a concern that though the book we had written had the potential to be influential among evangelicals—it was thoroughly orthodox, evangelical in its tone, and Collins and I were respected within the community—all the things that would be useful about it would be undermined by the last chapter. Readers would say, who do they think they are rewriting scripture.

I think this reflects the low value evangelicals place on art; what I was doing was a creative, not theological exercise, but I was inclined to cooperate with my editor. So I just took that out. I left in the story to some degree, but I didn't try to tie it to any rewrite of Genesis.

The book was successful and we were all happy with that, but I kind of had this project sitting around. So I approached Lil Copan who was an editor at Paraclete at the time and she liked it a lot. She suggested that I write a little short book—she described it as the kind of thing you do in a long weekend. She really liked the sample chapter a lot, and made some great suggestions and then brought it to the marketing people there. They said they wanted to publish it, but they liked it so much that they wanted to boost it from a 20,000-word book to 40-45,000. So they asked me to do that.

How should readers approach this book? How was the process of writing it different from your other books?

The book needs to be understood as a creative exercise. It's as if someone said, paint a picture of Jesus at Starbucks, or tell a story about Jesus going to Walmart. You have to give someone creative license to do that.

One of the first things I had to do was figure out how to divide the history of the universe from the big bang to the present into seven periods. And I'm not doing that because I want to suggest that the days of Genesis are 2 billion years long and if you just make that change everything will line up, but it's a way to keep it connected to the Genesis story.