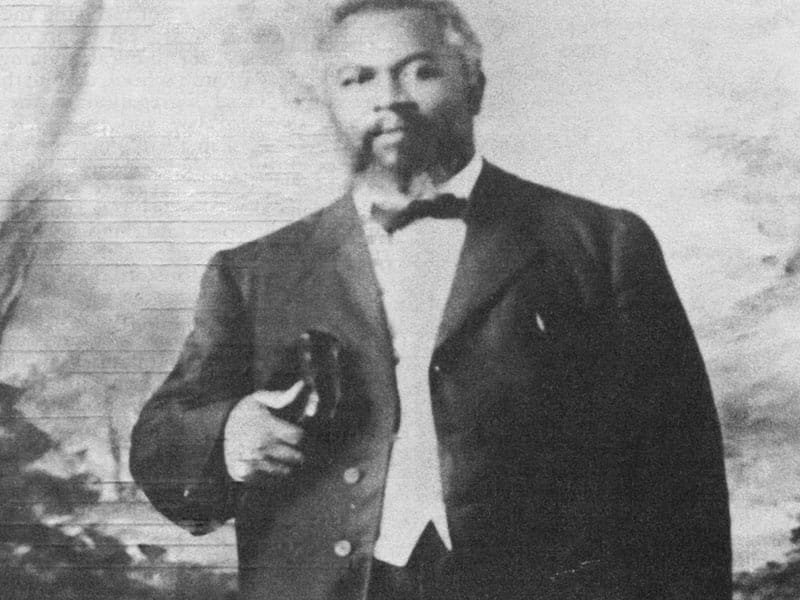

- Profession: Preacher

- Lived: May 2, 1870 - September 28, 1922 (Modern)

- Nationality: American

- Known for: Co-founder of Pentecostalism

Elements of Pentecostalism are woven throughout Christian history and its modern roots can be traced to John Wesley in the 1700s with his promotion of Christian perfection as a model of holy living, stressing grace, sanctification, and social reform. The founding of the current Pentecostal movement begins two centuries later, with William J. Seymour, the son of former slaves born in Louisiana. After working a series of jobs, and exploring the call to ministry in several churches, Seymour moved to Indianapolis and joined Daniel S. Warner's Church of God movement (in Anderson, Indiana), nicknamed the "Evening Light Saints." This intentionally multiracial movement was deeply rooted in ideals of social reform and allowed Seymour to begin his pastoral career preaching to mixed audiences as he formed his own ideas about race and faith.

Seymour traveled to Houston to take classes at the Bible school of fellow Pentecostal founder, Charles F. Parham. In accordance with the racial norms of 1905, as an African American, Seymour had to wait outside the classroom and listen to the lecture. What he heard from Parham seemed to convince him of the necessity of another experience after sanctification that would be accompanied by the evidence of speaking in tongues. Seymour was invited to preach at a small Holiness church in Los Angeles, but found a less than receptive audience when he began preaching about the Pentecostal baptism. By all accounts, Seymour had not experienced the baptism yet, which was unusual and caused his Holiness congregation to wonder why he would be preaching about something he had yet to experience. A small group from the Holiness church decided to support Seymour's preaching and allowed him to use one of their homes, on Bonnie Brae Street, as a base where he would, in effect, begin the American Pentecostal movement in 1906.

Seymour's preaching drew huge crowds, so large that they moved to an abandoned African Methodist Episcopal church in downtown Los Angeles, the Azusa Street Mission. Hundreds came to hear about this new outpouring of the Holy Spirit, and often the meetings spilled out into the streets. Finally, after months of preaching and praying for such an outpouring, Seymour-along with a church full of witnesses and pastoral staff-experienced the baptism of the Holy Spirit on April 9, 1906, accompanied by speaking in tongues. The spiritual nature of the event would have been revolutionary enough if it hadn't also been combined with the social nature of the meetings. Different races and ethnicities as well as women and men worshipped side by side. Such revolutionary happenings in Los Angeles were welcomed by Seymour, who viewed racial egalitarianism as part of his mission. Unfortunately that unrestricted spirit would not outlast the Azusa Street revival, which lasted from 1906 to 1909.

Thanks to the work of the church stenographer, Seymour's sermons and thoughts about the Azusa Street Revival were preserved and transmitted through the pages of the mission's newspaper, The Apostolic Faith. In addition, Seymour attempted to codify the theology of Azusa Street in a book called Doctrines and Discipline of Azusa Street Apostolic Mission of Los Angeles. But according to historian Douglas Jacobsen, Seymour's writing is little more than the African Methodist Episcopal's book of discipline with a few of Seymour's thoughts interspersed throughout the document.

Not everything went well at Azusa Street. Since the much heralded revival, which was for many a sign of the end times, occurred at a predominately African American church, Seymour's legitimacy as a Pentecostal leader was in question from the beginning. Seymour not only survived the local criticisms from the religious and civil leadership of Los Angeles, but he survived two attempted coups of his pastorate, one by his old teacher, Charles Parham, and another by Chicago-based evangelist, William Durham.

The realities of turn-of-the-century Los Angeles forced Seymour to concede that if the Azusa Street Mission were to survive past the revival stage, it would soon have to revert back to what it started out as-an African American congregation with "colored" leadership-to ensure its survival amid the hostile racial atmosphere of southern California. Seymour and his wife Jenny ran the church; William died in 1922, Jenny in 1931. The property was sold to pay back taxes, and in what would be a cruel twist of fate, this Pentecostal paradise was torn down for a parking lot.

The effects of Azusa Street were far-reaching, though, in part because of people receiving the Spirit baptism there and promptly leaving the U.S. to spread the message globally—many of those early missionaries were women who traveled alone to places such as China, India, and various countries in Africa and Latin America. There they often founded churches and orphanages, and were the de facto leaders of the Pentecostal movement's early foray as a world religion. By 1908, Pentecostal missionaries were in fifty nations by 1908. In the U.S., as in other parts of the globe, Pentecostalism is growing, but usually within specific racial and ethnic groups. Pentecostals and charismatics combine to make up roughly 2 billion Christians worldwide, the largest Christian group outside the Roman Catholic Church. (Source: Patheos Religion Library)

Seymour traveled to Houston to take classes at the Bible school of fellow Pentecostal founder, Charles F. Parham. In accordance with the racial norms of 1905, as an African American, Seymour had to wait outside the classroom and listen to the lecture. What he heard from Parham seemed to convince him of the necessity of another experience after sanctification that would be accompanied by the evidence of speaking in tongues. Seymour was invited to preach at a small Holiness church in Los Angeles, but found a less than receptive audience when he began preaching about the Pentecostal baptism. By all accounts, Seymour had not experienced the baptism yet, which was unusual and caused his Holiness congregation to wonder why he would be preaching about something he had yet to experience. A small group from the Holiness church decided to support Seymour's preaching and allowed him to use one of their homes, on Bonnie Brae Street, as a base where he would, in effect, begin the American Pentecostal movement in 1906.

Seymour's preaching drew huge crowds, so large that they moved to an abandoned African Methodist Episcopal church in downtown Los Angeles, the Azusa Street Mission. Hundreds came to hear about this new outpouring of the Holy Spirit, and often the meetings spilled out into the streets. Finally, after months of preaching and praying for such an outpouring, Seymour-along with a church full of witnesses and pastoral staff-experienced the baptism of the Holy Spirit on April 9, 1906, accompanied by speaking in tongues. The spiritual nature of the event would have been revolutionary enough if it hadn't also been combined with the social nature of the meetings. Different races and ethnicities as well as women and men worshipped side by side. Such revolutionary happenings in Los Angeles were welcomed by Seymour, who viewed racial egalitarianism as part of his mission. Unfortunately that unrestricted spirit would not outlast the Azusa Street revival, which lasted from 1906 to 1909.

Thanks to the work of the church stenographer, Seymour's sermons and thoughts about the Azusa Street Revival were preserved and transmitted through the pages of the mission's newspaper, The Apostolic Faith. In addition, Seymour attempted to codify the theology of Azusa Street in a book called Doctrines and Discipline of Azusa Street Apostolic Mission of Los Angeles. But according to historian Douglas Jacobsen, Seymour's writing is little more than the African Methodist Episcopal's book of discipline with a few of Seymour's thoughts interspersed throughout the document.

Not everything went well at Azusa Street. Since the much heralded revival, which was for many a sign of the end times, occurred at a predominately African American church, Seymour's legitimacy as a Pentecostal leader was in question from the beginning. Seymour not only survived the local criticisms from the religious and civil leadership of Los Angeles, but he survived two attempted coups of his pastorate, one by his old teacher, Charles Parham, and another by Chicago-based evangelist, William Durham.

The realities of turn-of-the-century Los Angeles forced Seymour to concede that if the Azusa Street Mission were to survive past the revival stage, it would soon have to revert back to what it started out as-an African American congregation with "colored" leadership-to ensure its survival amid the hostile racial atmosphere of southern California. Seymour and his wife Jenny ran the church; William died in 1922, Jenny in 1931. The property was sold to pay back taxes, and in what would be a cruel twist of fate, this Pentecostal paradise was torn down for a parking lot.

The effects of Azusa Street were far-reaching, though, in part because of people receiving the Spirit baptism there and promptly leaving the U.S. to spread the message globally—many of those early missionaries were women who traveled alone to places such as China, India, and various countries in Africa and Latin America. There they often founded churches and orphanages, and were the de facto leaders of the Pentecostal movement's early foray as a world religion. By 1908, Pentecostal missionaries were in fifty nations by 1908. In the U.S., as in other parts of the globe, Pentecostalism is growing, but usually within specific racial and ethnic groups. Pentecostals and charismatics combine to make up roughly 2 billion Christians worldwide, the largest Christian group outside the Roman Catholic Church. (Source: Patheos Religion Library)

Back to Search Results