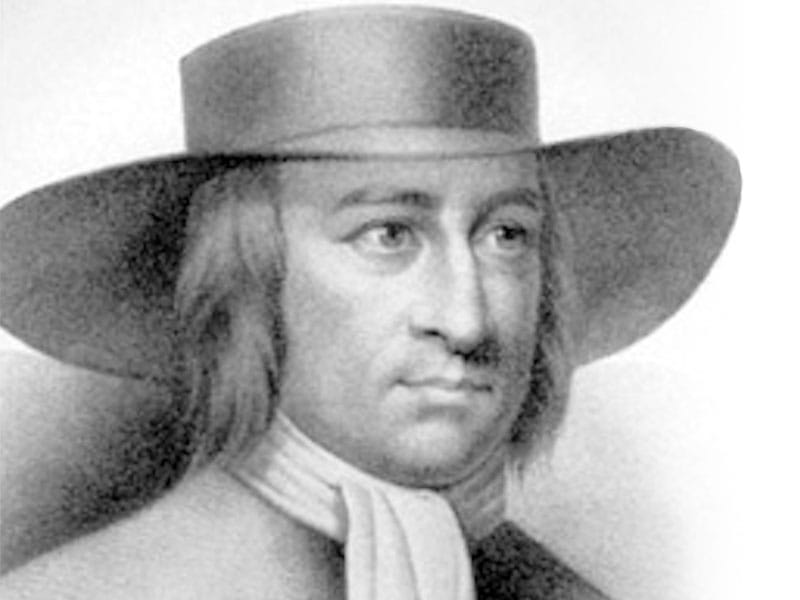

- Lived: July 1624 - January 13, 1691 (Great Awakening)

- Nationality: English

- Known for: Founder of the Religious Society of Friends, known as the Quakers

George Fox came of age in the mid-1600s, a turbulent time in England, as scattered wars and skirmishes played out between those favoring different forms of government—with and without royalty—and different religions—Anglicans, other Protestants, and Catholics. This was the time of the English Dissenters, a diverse collection of non-Anglican Protestants, including the Puritans, who disapproved of the Church of England’s official role. Preachers promoted different beliefs and styles directly to the public in the streets. Having been raised by a churchwarden and weaver father in a rural setting, Fox favored simple work and opposed credentialed academicism. Though his curiosity about faith led him to pursue religious studies, this consisted mostly of reading the Bible and developing beliefs based on his own discernment of God’s guidance.

Fox started preaching in public places in his early twenties, and quickly developed a small following. He spoke against church corruption and mandatory tithes, and also for personal purity in the Puritan vein. He developed and started promoting the view that worship should consist of lay congregants sharing words as moved to do so by the Holy Spirit, with no deference to clergy, credentials, status or gender. Fox and some of his followers started traveling the country, sharing their beliefs. His opposition to tithes, which were supporting powerful church leaders, compounded by his refusal to swear an oath in court, led to arrests and imprisonment. At the same time, other Dissenters were frustrated by Fox’s refusal to support violence in defense of their causes. Fox won Cromwell’s personal support, however, and avoided execution. Arrests of Quakers continued. Rather than breaking Fox’s spirit, this hardened his opposition to the state church. Persecution continued with the return of the monarchy, and spread to the colonies.

In his 40s, Fox traveled to America to preach, to help Quakers there organize, and to appeal to political leaders not to persecute his followers. After returning, he was arrested a few more times, though persecution of Quakers had begun to fade. He continued to travel and write letters, and dictated an autobiography that was published posthumously. While there is by definition no clergy or central leader in the Religious Society of Friends, Fox shaped the movement and quelled dissent.

Much of that dissent revolved around the central Quaker concept of the Inner Light, based on John 1:9: “The true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world.” Quakers believe every person is equally enlightened by Christ, and by extension, that all are equal in that light. At various points, some members or others have had trouble embracing the idea that the equality of treatment and standing implied and demanded by the presence of this Inner Light applies to some group or another—women, those of African descent, Native Americans.

Today, Quakers still are known for this dedication to equality for all, for their refusal to bow down to or make oaths to others, and especially for their pacifism, all of which continue to put them in opposition to the culture and sometimes the government. Though only about ten percent of Quakers still worship this way, the faith also is associated with the practice of silent or “unprogrammed” worship, in which members sit together in an unadorned room in silence broken only when members feel moved to share something for the benefit of the group.

Fox started preaching in public places in his early twenties, and quickly developed a small following. He spoke against church corruption and mandatory tithes, and also for personal purity in the Puritan vein. He developed and started promoting the view that worship should consist of lay congregants sharing words as moved to do so by the Holy Spirit, with no deference to clergy, credentials, status or gender. Fox and some of his followers started traveling the country, sharing their beliefs. His opposition to tithes, which were supporting powerful church leaders, compounded by his refusal to swear an oath in court, led to arrests and imprisonment. At the same time, other Dissenters were frustrated by Fox’s refusal to support violence in defense of their causes. Fox won Cromwell’s personal support, however, and avoided execution. Arrests of Quakers continued. Rather than breaking Fox’s spirit, this hardened his opposition to the state church. Persecution continued with the return of the monarchy, and spread to the colonies.

In his 40s, Fox traveled to America to preach, to help Quakers there organize, and to appeal to political leaders not to persecute his followers. After returning, he was arrested a few more times, though persecution of Quakers had begun to fade. He continued to travel and write letters, and dictated an autobiography that was published posthumously. While there is by definition no clergy or central leader in the Religious Society of Friends, Fox shaped the movement and quelled dissent.

Much of that dissent revolved around the central Quaker concept of the Inner Light, based on John 1:9: “The true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world.” Quakers believe every person is equally enlightened by Christ, and by extension, that all are equal in that light. At various points, some members or others have had trouble embracing the idea that the equality of treatment and standing implied and demanded by the presence of this Inner Light applies to some group or another—women, those of African descent, Native Americans.

Today, Quakers still are known for this dedication to equality for all, for their refusal to bow down to or make oaths to others, and especially for their pacifism, all of which continue to put them in opposition to the culture and sometimes the government. Though only about ten percent of Quakers still worship this way, the faith also is associated with the practice of silent or “unprogrammed” worship, in which members sit together in an unadorned room in silence broken only when members feel moved to share something for the benefit of the group.

Back to Search Results