What is the deal with celebrating Trinity Sunday? After all, isn’t every Mass a celebration of our Triune God? So why a special Sunday dedicated as a feast to God, in three persons?

That question is why I picked up my torch and started on a quest to find the origins of this feast day. In truth, an amicable tussle with a friend of mine is what led me on the search to solve this riddle. Want to come along?

See, he had posted a Wikipedia article that pointed to St. Thomas Becket as perhaps being the person responsible for our continued observance of this feast day. Joe Six-Pack, USMC, was not too sure of that assertion. I love St. Thomas Becket with the best of them, but should he be getting credit for the popularity of this feast? Really?

The Wikipedia citation for Trinity Sunday, which my Anglo-Catholic friend had posted, has this to say,

Thomas Becket (1118–70) was consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury on the Sunday after Pentecost (Whitsun), and his first act was to ordain that the day of his consecration should be held as a new festival in honour of the Holy Trinity. This observance spread from Canterbury throughout the whole of western Christendom.

OK, I’m the first to admit that I’m a mere grasshopper when it comes to knowing everything there is to know about Church history. It was probably rash of me to doubt that the beloved martyr was responsible for the feast being placed on the calendar as it is today. But before I could stop myself, I threw a penalty flag, called foul, and started digging.

At first, it was looking like I was in the clear, as the citation for Trinity Sunday at ye olde Catholic Encyclopedia didn’t even mention St.Thomas Becket. At all. See for yourself.

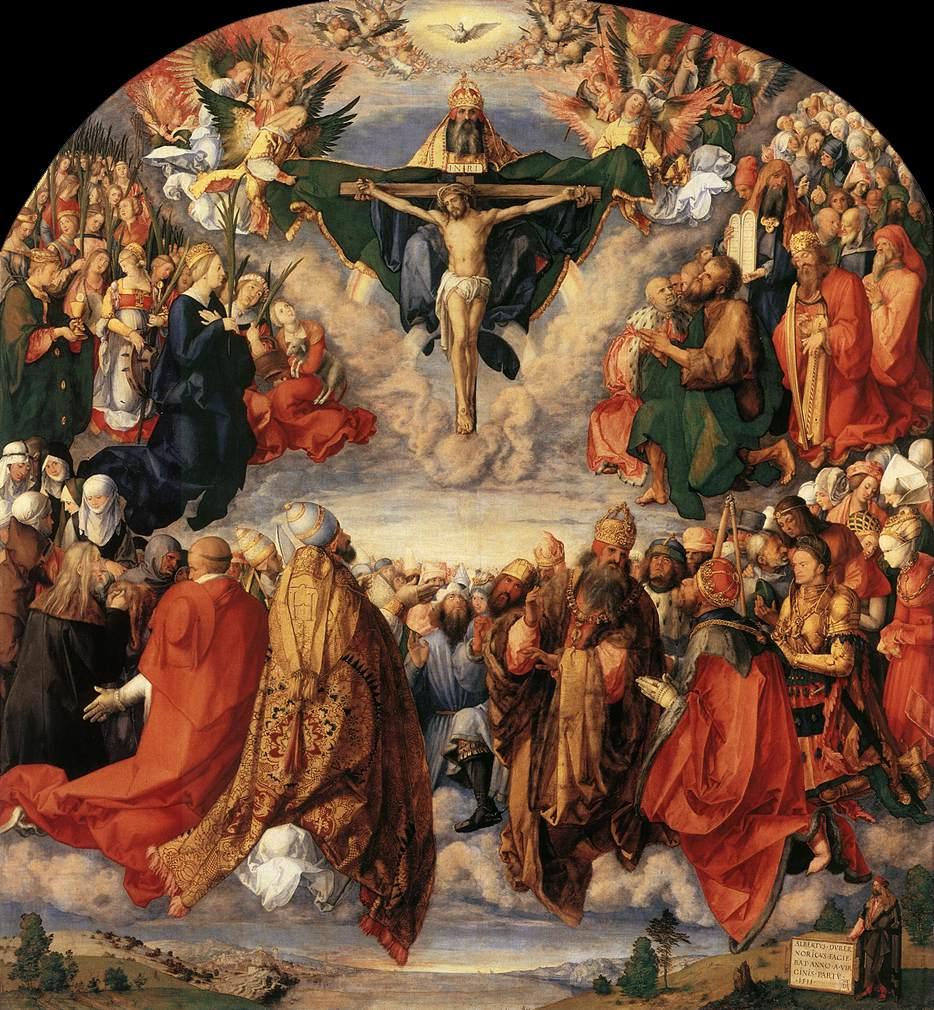

The first Sunday after Pentecost, instituted to honour the Most Holy Trinity. In the early Church no special Office or day was assigned for the Holy Trinity. When the Arian heresy was spreading the Fathers prepared an Office with canticles, responses, a Preface, and hymns, to be recited on Sundays. In the Sacramentary of St. Gregory the Great (P.L., LXXVIII, 116) there are prayers and the Preface of the Trinity. The Micrologies (P.L., CLI, 1020), written during the pontificate of Gregory VII (Nilles, II, 460), call the Sunday after Pentecost a Dominica vacans, with no special Office, but add that in some places they recited the Office of the Holy Trinity composed by Bishop Stephen of Liège (903-20) By other the Office was said on the Sunday before Advent. Alexander II (1061-1073), not III (Nilles, 1. c.), refused a petition for a special feast on the plea, that such a feast was not customary in the Roman Church which daily honoured the Holy Trinity by the Gloria, Patri, etc., but he did not forbid the celebration where it already existed. John XXII (1316-1334) ordered the feast for the entire Church on the first Sunday after Pentecost. A new Office had been made by the Franciscan John Peckham, Canon of Lyons, later Archbishop of Canterbury (d. 1292). The feast ranked as a double of the second class but was raised to the dignity of a primary of the first class, 24 July 1911, by Pius X (Acta Ap. Sedis, III, 351). The Greeks have no special feast. Since it was after the first great Pentecost that the doctrine of the Trinity was proclaimed to the world, the feast becomingly follows that of Pentecost.

Heh!

For the life of me, I couldn’t seem to find much to corroborate the crediting of Becket with the initiation of this feast. The above citation notes dates substantially earlier than when Becket was Archbishop of Canterbury, and so I thought I had a case closed situation.

Huzzah!

So I looked for another source that would help my unbelief with eagerness. I thought I had found the same with the help of Scott Reichert’s column at About.com. I scanned it briefly, but alas, it too circled back to Becket after covering what I found in the citation you read above. To wit,

To stress the doctrine of the Trinity, other Fathers of the Church, such as St. Ephrem the Syrian, composed prayers and hymns that were recited in the Church’s liturgies and on Sundays as part of the Divine Office, the official prayer of the Church. Eventually, a special version of this office began to be celebrated on the Sunday after Pentecost, and the Church in England, at the request of St. Thomas à Becket (1118-1170), was granted permission to celebrate Trinity Sunday. The celebration of Trinity Sunday was made universal by Pope John XXII (1316-34).

Whaat? Joe Six-Pack’s confidence began to shake a little bit. So I began to dig some more. Time to break out the steam shovel to see what could be found. I unearthed a website called churchyear.net , that had a lengthy citation that included the following,

“Trinity Sunday has been especially popular in England, perhaps because Thomas Becket was consecrated on Trinity Sunday, AD 1162.”

Aha! Perhaps sounded a little less authoritative than what I’d seen so far. I figured it was time to hit Google Books and put this mystery to bed.

Much to my chagrin, though, it was looking like my friend was right. See, I found an old book (which I’ve since added to the collection of the YIMCatholic Bookshelf) published in 1859 by John Morris entitled, The Life And Martyrdom Of St. Thomas Becket. Therein he writes,

Thus, on the Octave of Pentecost, Trinity Sunday, the 3d of June 1162, St. Thomas was consecrated a Bishop in his metropolitan church by Henry of Winchester, in the presence of nearly all his suffragans, as well as of a vast multitude of abbots, religious, clerics, and nobles, Prince Henry himself being there. St. Thomas decreed that the Feast of the Blessed Trinity should be observed every year as a solemn festival in his church of Canterbury.

Gulp. It was starting to look like Joe Six-Pack was going to have a Fonzie moment.

In a last ditch effort to avoid that fate, I headed back to the Catholic Encyclopedia and searched the citation for St. Thomas Becket. What I found didn’t look good for the home team, gang.

“He was ordained priest on Saturday in Whitweek and consecrated bishop the next day, Sunday, 3 June, 1162. It seems to have been St. Thomas who obtained for England the privilege of keeping the feast of the Blessed Trinity on that Sunday, the anniversary of his consecration, and more than a century afterwards this custom was adopted by the papal Court, itself and eventually imposed on the whole world.”

And so I thought, game over. In fact, I conceded the floor to my friend on that source. I didn’t say exactly I was wrong, though. I simply said that he was right.

But you know what? I just had to keep digging, because even that citation said, seems to have. My mind wandered back to that first Catholic Encyclopedia citation, what with the Arians, Gregory the Great, and the bishop of Liège, etc., and I figured there had to be more to the origins of this solemnity. My friend and I had had our fun, but I just wanted to know more. Chalk it up to an insatiable thirst for truth.

So I went back to Google Books for a third time and this time I ran a search for Feast of the Holy Trinity Thomas Becket. I found a clue that drew me away from the British Isles, further back in time, and back to continental Europe.

Guess who helped me out? A Jesuit, that’s who. And not one of my favorites from The Dead Jesuits, but one who is alive and well. Yes!

Joseph N. Tylenda, SJ, published a handy guide in 2003, called, Saints and Feasts of the Liturgical Year, wherein he writes in his brief on today’s Solemnity the following.

The earliest reference to a feast honoring the Blessed Trinity is in Tours, in 796. The feast was later introduced at Cluny in 1091, and St. Thomas Becket adopted it at Canterbury in 1162.

“Come, Watson, come! The game is afoot. Not a word! Into your clothes and come!”

Time to find out more about this St. Alcuin cat, saavy? Because it sounded to me like what we have here is another chicken and egg problem. From this source it seemed certain that St. Thomas didn’t invent the feast, but that he simply adored it and promulgated it because of his love for God, and perhaps to honor the miraculousness of his own highly unlikely ordination.

So it was back to the library to learn more about St. Alcuin. Boy howdy, that guy is one interesting person. Turns out he had a patron by the name of Charlemagne. Uh-huh. And he played a role in the Carolingian Renaissance, which is kind of a big deal. The fact that it even happened puts the lie to calling this time frame The Dark Ages, though it may have been a bit of a false dawn, as opposed to being a full-on, cross-cultural, renaissance, which is probably why John Q. Public has never even heard of it. The ivory tower types over at Princeton credit Alcuin with having a hefty amount of influence during this time.

But the really big thing I was concerned with is what did he have to do with today’s feast? Turns out plenty. The Wikipedia citation puts him in Tours in 796, so I was getting warmer. Here’s the quick and dirty biography on this key player.

Alcuin was an Englishman from York, born into a noble family about 730, and educated by a pupil of Bede. Having become a deacon, he was made head of the cathedral school at York around 770. In 781 he was asked by the Emperor Charlemagne to become his minister of education. He accepted, and established schools at many cathedrals and monasteries, and promoted learning in every way he could. In the preceding years of constant wars and invasions, many ancient writings had been lost. Alcuin established scriptoria, dedicated to the copying and preservation of ancient manuscripts, both pagan and Christian. That we have as much as we do of the writings of classical Roman authors is largely due to Alcuin and his scribes.

As a result of this, deacons everywhere are standing a little taller. Alcuin is a hero of historical preservation. He should be the patron saint of archivists, if you ask me. As for the feast at hand, here is why he ranks highest. My search led me to a post by the good folks over at Catholic Culture, where I learned that,

to counteract the Arian heresy, which denied the fullness of divinity to the Son, a special Mass text in honor of the Holy Trinity was introduced and incorporated in the Roman liturgical books. This Mass was not assigned for a definite day but could be used on certain Sundays according to the private devotion of each priest. (Such Mass texts which are not prescribed but open to choice on certain days are now known as “votive Masses.”) From the ninth century on, various bishops of the Frankish kingdoms promoted in their own dioceses a special feast of the Holy Trinity, usually on the Sunday after Pentecost. They used a Mass text that Abbot Alcuin (804) is said to have composed.

Abbot who? In what century? You can bet I rushed to tell me friend of my findings, pronto. To cap this all off, I again turned to Google and found a website that linked to a reprint of Dom Guéranger, Abbot of Solesmes’s book, The Liturgical Year. It’s too lengthy to post in its entirety here, but I’ll give you the quick and dirty on the origins of today’s Solemnity,

The idea of such a feast was first conceived by some of those pious and recollected souls, who are favored from on high with a sort of presentiment of the things which the Holy Ghost will achieve, at a future period, in the Church. So far back as the eighth century, the learned monk Alcuin had the happy thought of composing a Mass in honor of the mystery of the Blessed Trinity. It would seem that he was prompted to this by the apostle of Northern Germany, Saint Boniface. That this composition is a beautiful one, no one will doubt who knows, from Alcuin’s writings, how full its author was of the spirit of the sacred liturgy; but, after all, it was only a votive Mass, a mere help to private devotion, which no one ever thought would lead to the institution of a feast. This Mass, however, became a great favorite, and was gradually circulated through the several Churches; for instance, it was approved of for Germany by the Council of Seligenstadt, held in 1022.

In the previous century, however, a feast properly so-called of the Holy Trinity had been introduced into one of the Churches of Belgium (ed. the Abbot Alcuin’s)—the very same that was to have the honor, later on, of procuring to the Church’s calendar, one of the richest of its solemnities. Stephen, Bishop of Liege, solemnly instituted the Feast of the Holy Trinity for his Church, in 920, and had an entire Office composed in honor of the mystery. Riquier, Stephen’s successor in the See of Liege, kept up what his predecessor had begun.

The feast was gradually adopted. The Benedictine Order took it up from the very first. We find, for instance, in the early part of the 11th century, that Berno, the Abbot of Reichenau, was doing all he could to propagate it. At Cluny, also, the feast was established at the commencement of the same century, as we learn from the Ordinarium of that celebrated monastery, drawn up in 1091, in which we find mention of Holy Trinity Day as having been instituted long before.

In England it was the glorious Martyr, St. Thomas a Becket, who established the Feast of the Holy Trinity. He introduced it into his archdiocese of Canterbury in the year 1162, in memory of his having been consecrated Bishop on the First Sunday after Pentecost. Some Churches celebrated this feast, not on the First, but on the Last Sunday after Pentecost; some on both the First and Last Sundays.

It was evident, from all this, that the Apostolic See would finally give its sanction to a practice, whose universal adoption was being prompted by Christian instinct. Pope John XXII, who sat in the Chair of St. Peter as early as the year 1334, completed the work by a decree, wherein the Church of Rome accepted the Feast of the Holy Trinity, and extended its observance to all Churches.

As to the motive which induced the Church, led as She is in all things by the Holy Ghost, to fix one special day in the year for the offering of a solemn homage to the Blessed Trinity, whereas all our adorations, all our acts of thanksgiving, all our petitions, are ever being presented to It: such motive is to be found in the change which was being introduced, at that period, into the liturgical calendar. Up to about the year 1000, the Feasts of the Saints, marked on the general calendar and universally kept, were very few. From that time, they began to be more numerous; and it was evident that their number would go on increasing. The time would come, when the Sunday’s Office, which is specially consecrated to the Blessed Trinity, must make way for that of the Saints, as often as one of their Feasts occurred on a Sunday. As a sort of compensation for this celebration of the memory of God’s servants on the very day which was sacred to the Holy Trinity, it was considered right that once, at least, in the course of the year, a Sunday should be set apart for the exclusive and direct expression of the worship which the Church pays to our great God, Who has vouchsafed to reveal Himself to mankind in His ineffable Unity and in His eternal Trinity.

So long post short, my friend and I are both right.

St. Alcuin wrote the original votive Mass to commemorate this feast, it was formalized (is that the right word?) by Stephen, the bishop of of Liège, after which it was celebrated on the Continent, and later, St. Thomas raised its importance and promulgated it throughout the Church in England. Later still, Pope John XXII ordered it to be celebrated by the whole Church, and finally, in midsummer, 1911, Pope Pius X locked it down to this very day.

My work is done here.

Did I mention I’ve only barely scratched the surface on the saints and popes surrounding this topic? Man, I love learning this Catholic stuff.