I’ll be the first to admit that I’m late to the party of those who admire Neil Gaiman. I’ve only read a few of his graphic Sandman novels, and shared them with my children.

Today, though, a friend shared a post from Gaiman’s website in which he acknowledges the debt he owes to three giants of literature, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and G.K. Chesterton, as well as to the treasures that can be unearthed in libraries. It’s a confession, of sorts, that he made in a speech given in 2004 to a body of literati known as the Mythopoeic Society.

What little I know about Mr. Gaiman, I like. I suspect you’ll enjoy meeting him in his own words too.

I thought I’d talk about authors, and about three authors in particular, and the circumstances in which I met them.

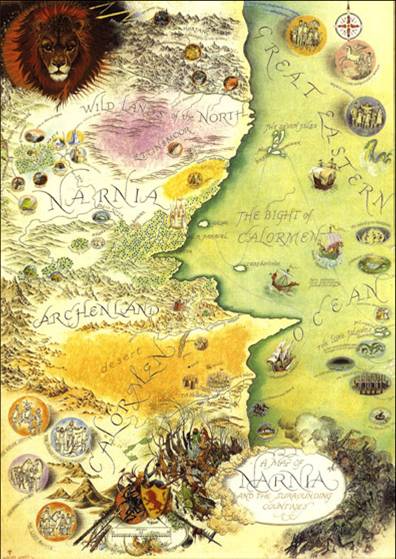

There are authors with whom one has a personal relationship and authors with whom one does not. There are the ones who change your life and the ones who don’t. That’s just the way of it.I was six years old when I saw an episode of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe in black and white on television at my grandmother’s house in Portsmouth. I remember the beavers, and the first appearance of Aslan, an actor in an unconvincing lion costume, standing on his hind legs, from which I deduce that this was probably episode two or three. I went home to Sussex and saved my meagre pocket money until I was able to buy a copy of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe of my own. I read it, and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, the other book I could find, over and over, and when my seventh birthday arrived I had dropped enough hints that my birthday present was a boxed set of the complete Narnia books. And I remember what I did on my seventh birthday — I lay on my bed and I read the books all through, from the first to the last.

For the next four or five years I continued to read them. I would read other books, of course, but in my heart I knew that I read them only because there wasn’t an infinite number of Narnia books to read.

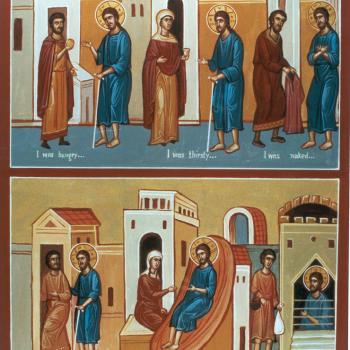

For good or ill the religious allegory, such as it was, went entirely over my head, and it was not until I was about twelve that I found myself realising that there were Certain Parallels. Most people get it at the Stone Table; I got it when it suddenly occurred to me that the story of the events that occurred to Saint Paul on the road to Damascus was the dragoning of Eustace Scrubb all over again. I was personally offended: I felt that an author, whom I had trusted, had had a hidden agenda. I had nothing against religion, or religion in fiction — I had bought (in the school bookshop) and loved The Screwtape Letters, and was already dedicated to G.K. Chesterton. My upset was, I think, that it made less of Narnia for me, it made it less interesting a thing, less interesting a place. Still, the lessons of Narnia sank deep. Aslan telling the Tash worshippers that the prayers he had given to Tash were actually prayers to Him was something I believed then, and ultimately still believe.

The Pauline Baynes map of Narnia poster stayed up on my bedroom wall through my teenage years.

I hate to pry you away from your other duties, but you’re going to want to read the entire speech.You’ll probably want to bookmark Gaiman’s Jornal, while you’re at it.