Truth is stranger than fiction. And weird things happen when governments decide to help you decide how many children you can have.

Take Singapore, for instance. The island nation, after gaining its independence from Malaysia in 1965 had a total fertility rate (children born per woman) north of 4.7 (down from 5.41 in 1960). As demographers know, a nation needs a TFR of 2.1 to maintain itself for the long run. The Singapore government was spooked by this high TFR and was determined to remedy the situation.

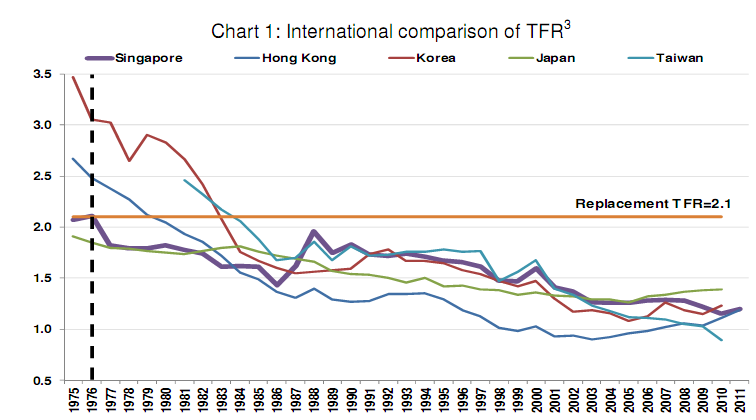

What they wound up doing is pretty clear. They put Singapore on a path to extinction. And as a result, its estimated that Singapore’s TFR hit an all-time low of 1.11 last year, which puts it at the bottom of the heap of all the countries in the world (this year the estimate is==>> 0.78). Here’s the skinny on the Singapore governments population control policies from the Library of Congress Country Studies, current up to 1989. It’s the tale of unfettered, nay, promoted, contraception, sterilizations, and abortions, from 1965-1972 until an “aha moment” in the 80’s, followed by a “pull out all the stops for babies!” move today.

First the background,

Singapore, Population Control Policies

Since the mid-1960s, Singapore’s government has attempted to control the country’s rate of population growth with a mixture of publicity, exhortation, and material incentives and disincentives. Falling death rates, continued high birth rates, and immigration from peninsular Malaya during the decade from 1947 to 1957 produced an annual growth rate of 4.4 percent, of which 3.4 percent represented natural increase and 1.0 percent immigration. The crude birth rate peaked in 1957 at 42.7 per thousand. Beginning in 1949, family planning services were offered by the private Singapore Family Planning Association, which by 1960 was receiving some government funds and assistance. By 1965 the crude birth rate was 29.5 per 1,000 and the annual rate of natural increase had been reduced to 2.5 percent. Singapore’s government saw rapid population growth as a threat to living standards and political stability, as large numbers of children and young people threatened to overwhelm the schools, the medical services, and the ability of the economy to generate employment for them all. In the atmosphere of crisis after the 1965 separation from Malaysia, the government in 1966 established the Family Planning and Population Board, which was responsible for providing clinical services and public education on family planning.

Birth rates fell from 1957 to 1970, but then began to rise as women of the postwar baby boom reached child-bearing years. The government responded with policies intended to further reduce the birth rate. Abortion and voluntary sterilization were legalized in 1970. Between 1969 and 1972, a set of policies known as “population disincentives” were instituted to raise the costs of bearing third, fourth, and subsequent children. Civil servants received no paid maternity leave for third and subsequent children; maternity hospitals charged progressively higher fees for each additional birth; and income tax deductions for all but the first two children were eliminated. Large families received no extra consideration in public housing assignments, and top priority in the competition for enrollment in the most desirable primary schools was given to only children and to children whose parents had been sterilized before the age of forty. Voluntary sterilization was rewarded by seven days of paid sick leave and by priority in the allocation of such public goods as housing and education. The policies were accompanied by publicity campaigns urging parents to “Stop at Two” and arguing that large families threatened parents’ present livelihood and future security. The penalties weighed more heavily on the poor, and were justified by the authorities as a means of encouraging the poor to concentrate their limited resources on adequately nurturing a few children who would be equipped to rise from poverty and become productive citizens.

How progressive of them, eh? Maybe things just stabilized at 2.10, and all would be well. Singapore is a smart country, you know. What could go wrong?

Fertility declined throughout the 1970s, reaching the replacement level of 2.006 in 1975, and thereafter declining below that level. With fertility below the replacement level, the population would after some fifty years begin to decline unless supplemented by immigration. In a manner familiar to demographers, Singapore’s demographic transition to low levels of population growth accompanied increases in income, education, women’s participation in paid employment, and control of infectious diseases. It was impossible to separate the effects of government policies from the broader socioeconomic forces promoting later marriage and smaller families, but it was clear that in Singapore all the factors affecting population growth worked in the same direction. The government’s policies and publicity campaigns thus probably hastened or reinforced fertility trends that stemmed from changes in economic and educational structures. By the 1980s, Singapore’s vital statistics resembled those of other countries with comparable income levels but without Singapore’s publicity campaigns and elaborate array of administrative incentives.

Nothing sells like advertising, or in Singapore’s case, propaganda backed up with hefty financial penalties for having more than two children. I mean, if having two costs this much, having one instead could only be better, right? Enter the shadow of demographic winter from stage right.

By the 1980s, the government had become concerned with the low rate of population growth and with the relative failure of the most highly educated citizens to have children. The failure of female university graduates to marry and bear children, attributed in part to the apparent preference of male university graduates for less highly educated wives, was singled out by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew in 1983 as a serious social problem. In 1984 the government acted to give preferential school admission to children whose mothers were university graduates, while offering grants of S$10,000 (for value of the Singapore dollar–see Glossary) to less educated women who agreed to be sterilized after the birth of their second child

Yes, applying both the carrot and the stick, to two distinct groups simultaneously. Very progressive. Guess what else they did? They set up a dating service for the educated elites.

The government also established a Social Development Unit (SDU) to act as matchmaker for unmarried university graduates. The policies, especially those affecting placement of children in the highly competitive Singapore schools, proved controversial and generally unpopular. In 1985 they were abandoned or modified on the grounds that they had not been effective at increasing the fecundity of educated women.

Stand by for extra cash and prizes. Will that work to turn around the downward slide?

In 1986 the government also decided to revamp its family planning program to reflect its identification of the low birth rate as one of the country’s most serious problems. The old family planning slogan of “Stop at Two” was replaced by “Have Three or More, if You Can Afford It.” A new package of incentives for large families reversed the earlier incentives for small families.

And thus all the stops were pulled out. This is kind of like the order for final protective fires given in a defensive battle. Place all weapons on automatic and fire until your barrels melt.

It included tax rebates for third children, subsidies for daycare, priority in school enrollment for children from large families, priority in assignment of large families to Housing and Development Board apartments (ed. note 4 out of 5 families live in these units in Singapore), extended sick leave for civil servants to look after sick children and up to four years’ unpaid maternity leave for civil servants. Pregnant women were to be offered increased counseling to discourage “abortions of convenience” or sterilization after the birth of one or two children. Despite these measures, the mid-1986 to mid-1987 total fertility rate reached a historic low of 1.44 children per woman, far short of the replacement level of 2.1. The government reacted in October 1987 by urging Singaporeans not to “passively watch ourselves going extinct.” The low birth rates reflected late marriages, and the Social Development Unit extended its matchmaking activities to those holding Advanced level (A-level) secondary educational qualifications as well as to university graduates (see The School System , this ch.).

Nice. Now you just needed to have a high school diploma to be considered worthy of further procreation. Guess what happened next?

The government announced a public relations campaign to promote the joys of marriage and parenthood. In March 1989, the government announced a S$20,000 tax rebate for fourth children born after January 1, 1988. The population policies demonstrated the government’s assumption that its citizens were responsive to monetary incentives and to administrative allocation of the government’s medical, educational, and housing services.

—Data as of December 1989

I found some more information from the early 2000’s in a research paper, but it seems whatever the government tried to do to incent folks to have babies, it just never worked. It reminds me of the scaring that stock investors received in the Great Depression, one which prevented that entire generation from ever investing in stocks afterwards, despite the fact that they basically went straight up without leaving a skid mark for close to 40 years. Perhaps religion has something to do with this? Maybe, as only 18% of the population is Christian (up from 10% in 1980).

And where does that leave the government of Singapore today? Would you believe it has the government begging folks to have sex tonight? Well, actually yesterday, as Singapore is on the other side of the date-line, but you get the picture. The Wall Street Journal has the story, and I have the video of the little message Singapore put out for National Day, when they celebrate their independence. It’s called “National Night.” You’ll be pleased to know that it is sponsored by Mentos. Seriously. They’ve even got a Facebook page. Big Government working with Big Mammon is a world-wide phenomenon, see.

And fair warning…it’s a crass rap song about couples “doing their duty” for the Fatherland by having natural (read “unprotected”) sex (if you’re in a committed, financially secure relationship). Tonight. You may especially like the last line, aimed at those who may be “offended.” Okay, enough disclaimers…check it out (or not). Lyrics included so folks can sing along.

$900 dollar strollers?! Converted into U.S. dollars, that’s about $730, or waay more than what strollers are going for at Target.

Will the HHS Mandate end any differently? Probably, because America has a history of cherishing liberty and having a limited government. But still, the current Administration, though it may mean well, won’t be doing well by promoting the “preventive services” that seem like the cat’s meow today, but ruin our tomorrows.

I’d prefer the government just stay out of these decisions altogether, wouldn’t you? Wishful thinking, I know.

UPDATE:

I just came across some ideas on health, marriage, and other romantic things, by G.K. Chesterton. These thoughts are from his essay Mr. H.G. Wells and the Giants, published in 1905.

The mistake of all that medical talk lies in the very fact that it connects the idea of health with the idea of care. What has health to do with care? Health has to do with carelessness. In special and abnormal cases it is necessary to have care. When we are peculiarly unhealthy it may be necessary to be careful in order to be healthy. But even then we are only trying to be healthy in order to be careless. If we are doctors we are speaking to exceptionally sick men, and they ought to be told to be careful. But when we are sociologists we are addressing the normal man, we are addressing humanity. And humanity ought to be told to be recklessness itself. For all the fundamental functions of a healthy man ought emphatically to be performed with pleasure and for pleasure; they emphatically ought not to be performed with precaution or for precaution. A man ought to eat because he has a good appetite to satisfy, and emphatically not because he has a body to sustain. A man ought to take exercise not because he is too fat, but because he loves foils or horses or high mountains, and loves them for their own sake. And a man ought to marry because he has fallen in love, and emphatically not because the world requires to be populated. The food will really renovate his tissues as long as he is not thinking about his tissues. The exercise will really get him into training so long as he is thinking about something else. And the marriage will really stand some chance of producing a generous-blooded generation if it had its origin in its own natural and generous excitement. It is the first law of health that our necessities should not be accepted as necessities; they should be accepted as luxuries. Let us, then, be careful about the small things, such as a scratch or a slight illness, or anything that can be managed with care. But in the name of all sanity, let us be careless about the important things, such as marriage, or the fountain of our very life will fail.

The government of Singapore, and all other governments, should just let man be his romantic self, and then get out of the way. And here’s the tale of America’s own tragic eugenics history.

UPDATE II: In Singapore, an event not to miss. A series on Theology of the Body: The Ethics of Love and Sexuality, starting on August 30th. Register today!