There are other ways to Occupy Wall Street, you know. As owners in the boardroom. I’ve shared thoughts along these lines by folks like John Bogle, founder of the Vanguard Group of Investment Companies. He argues, and pretty convincingly, that the problem for a long time now is that a heretical form of capitalism, managers capitalism, has risen to prominence.

What has become of owners capitalism? Here is a surprising example. Meet the best, most effective, shareholder activists you are ever likely to come across: The Sisters of St. Francis. Yes, that St. Francis. The one so poor he was barefoot most of the time. Their strategy? Become activist investors by owning shares in corporations, not shunning them.

The New York Times has the story,

ASTON, Pa.

NOT long ago, an unusual visitor arrived at the sleek headquarters of Goldman Sachs in Lower Manhattan.

It wasn’t some C.E.O., or a pol from Athens or Washington, or even a sign-waving occupier from Zuccotti Park.

It was Sister Nora Nash of the Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia. And the slight, soft-spoken nun had a few not-so-humble suggestions for the world’s most powerful investment bank.

Way up on the 41st floor, in a conference room overlooking the World Trade Center site, Sister Nora and her team from the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility laid out their advice for three Goldman executives. The Wall Street bank, they said, should protect consumers, rein in executive pay, increase its transparency and remember the poor.

In short, Goldman should do God’s work— something that its chairman and chief executive, Lloyd C. Blankfein, once remarked that he did. (The joke bombed.)

Long before Occupy Wall Street, the Sisters of St. Francis were quietly staging an occupation of their own. In recent years, this Roman Catholic order of 540 or so nuns has become one of the most surprising groups of corporate activists around.

The nuns have gone toe-to-toe with Kroger, the grocery store chain, over farm worker rights; with McDonald’s, over childhood obesity; and with Wells Fargo, over lending practices. They have tried, with mixed success, to exert some moral suasion over Fortune 500 executives, a group not always known for its piety.

”We want social returns, as well as financial ones,” Sister Nora said, strolling through the garden behind Our Lady of Angels, the convent here where she has worked for more than half a century. She paused in front of a statue of Our Lady of Lourdes. “When you look at the major financial institutions, you have to realize there is greed involved.”

The Sisters of St. Francis are an unusual example of the shareholder activism that has ripped through corporate America since the 1980s. Public pension funds led the way, flexing their financial muscles on issues from investment returns to workplace violence. Then, mutual fund managers charged in, followed by rabble-rousing hedge fund managers who tried to shame companies into replacing their C.E.O.’s, shaking up their boards — anything to bolster the value of their investments.

The nuns have something else in mind: using the investments in their retirement fund to become Wall Street’s moral minority.

A PROFESSORIAL woman with a sculpted puff of gray hair, Sister Nora grew up in Limerick County, Ireland. She dreamed of becoming a missionary in Africa, but in 1959, she arrived in Pennsylvania to join the Sisters of St. Francis, an order founded in 1855 by Mother Francis Bachmann, a Bavarian immigrant with a passion for social justice. Sister Nora took her Franciscan vows of chastity, poverty and obedience two years later, in 1961, and has stayed put ever since.

In 1980, Sister Nora and her community formed a corporate responsibility committee to combat what they saw as troubling developments at the businesses in which they invested their retirement fund. A year later, in coordination with groups like the Philadelphia Area Coalition for Responsible Investment, they mounted their offensive. They boycotted Big Oil, took aim at Nestlé over labor policies, and urged Big Tobacco to change its ways.

Eventually, they developed a strategy combining moral philosophy and public shaming. Once they took aim at a company, they bought the minimum number of shares that would allow them to submit resolutions at that company’s annual shareholder meeting. (Securities laws require shareholders to own at least $2,000 of stock before submitting resolutions.) That gave them a nuclear option, in the event the company’s executives refused to meet with them.

Unsurprisingly, most companies decided they would rather let the nuns in the door than confront religious dissenters in public.

“You’re not going to get any sympathy for cutting off a nun at your annual meeting,” says Robert McCormick, chief policy officer of Glass, Lewis & Company, a firm that specializes in shareholder proxy votes. With their moral authority, he said, the Sisters of St. Francis “can really bring attention to issues.”

Go read the rest for free over at Yahoo! I don’t know about St. Francis liking this turn of events, but I think St. Clement of Alexandria (150-211 AD) would be proud of the Sisters. Who’s that, you ask? Why, he’s the fellow that wrote a little homily called Who Is the Rich Man That Shall be Saved? Here’s a snippet to get you started,

Perhaps the reason of salvation appearing more difficult to the rich than to poor men, is not single but manifold. For some, merely hearing, and that in an off-hand way, the utterance of the Saviour, “that it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of heaven,” despair of themselves as not destined to live, surrender all to the world, cling to the present life as if it alone was left to them, and so diverge more from the way to the life to come, no longer inquiring either whom the Lord and Master calls rich, or how that which is impossible to man becomes possible to God.

But others rightly and adequately comprehend this, but attaching slight importance to the works which tend to salvation, do not make the requisite preparation for attaining to the objects of their hope. And I affirm both of these things of the rich who have learned both the Saviour’s power and His glorious salvation. With those who are ignorant of the truth I have little concern.

Those then who are actuated by a love of the truth and love of their brethren, and neither are rudely insolent towards such rich as are called, nor, on the other hand, cringe to them for their own avaricious ends, must first by the word relieve them of their groundless despair, and show with the requisite explanation of the oracles of the Lord that the inheritance of the kingdom of heaven is not quite cut off from them if they obey the commandments; then admonish them that they entertain a causeless fear, and that the Lord gladly receives them, provided they are willing; and then, in addition, exhibit and teach how and by what deeds and dispositions they shall win the objects of hope, inasmuch as it is neither out of their reach, nor, on the other hand, attained without effort; but, as is the case with athletes — to compare things small and perishing with things great and immortal — let the man who is endowed with worldly wealth reckon that this depends on himself.

That was one helluva long sentence Clement! Before you go and sell all you have and donate it all to the Occupy Wall Street movement, go read the rest of his thoughts over at Early Christian Writings. For, like we learned in Sunday’s Gospel reading about “the Talents,” some are given 5, some 2, and some 1, or more. “Each according to their abilities.”

So, yes, you can be like the Sisters of St. Francis. As long as,

Seek ye therefore first the kingdom of God, and his justice, and all these things shall be added unto you.

Update: A Contrarian Way to Invest Like a Catholic.

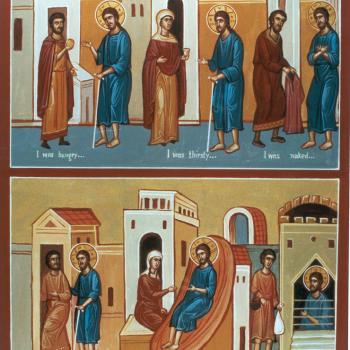

*Image Credit: Laura Pedrick for the New York Times.