About a month ago, I stumbled on this well-done essay on residential Zen training, The Freedom of No-Choice, by Roshi Bodhin Kjolhede, and posted it on the moodle that we use for the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training. My purpose was to expose Vine householder students to residential practice, if just through reading, in order to inform our work together … and to stir things up, of course.

About a month ago, I stumbled on this well-done essay on residential Zen training, The Freedom of No-Choice, by Roshi Bodhin Kjolhede, and posted it on the moodle that we use for the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training. My purpose was to expose Vine householder students to residential practice, if just through reading, in order to inform our work together … and to stir things up, of course.

Bodhin’s article has indeed evoked reflection and heartfelt responses on the Vine moodle and in practice meetings about the freedom that comes in home practice too when we let go of choice and just get up in the morning and sit, for example.

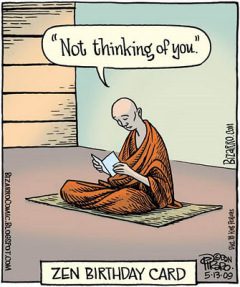

Another issue that has continued to percolate is that of comparing householder practice to residential/monastic practice (many householder Zen students think of their practice as second-rate and have feelings about that, I suppose because so much of Zen mythology is about monastics).

When I was doing monastic practice I wrote to a friend, bemoaning my lonely life (like the monk in the cartoon). She wrote back a long description of her householder life with two young kids, the stress of both her and her husband’s self-employment, the unreliability of health and income, and the fact that they had about $5.35 between the two of them and they were on their last roll of toilet paper.

“Stay where you are,” she said, “and (something to the effect of) quit whining!”

Likewise, Dogen admonishes us not to discuss the superiority or inferiority of a philosophy but to look at the authenticity of the actual practice. In other words, not the what but the how and why – not whether we do residential/monastic practice or householder practice but how we pour our hearts into our lives and open our hearts, lifing this great life.

Easy to say, sometimes hard to let go of looking around and just do.

Bodhin identifies three themes he sees in doing residential practice: simplicity (uncluttered surroundings of space and mind); order (the seniority system); and authority (as Bodhin puts it, “With ego-resistance futile, [s/]he is all but forced to surrender to the Great Way that is beyond self and other, beyond right and wrong”).

In householder practice, the mix and flavor of these three themes is different – and authority is especially so (even if your spouse or partner is the boss of you) – and there are a couple others that I think important.

Order and authority are powerful drivers in residential practice and by surrendering to the schedule and the directions of others, we are blown along with the wind of the buddhadharma (ideally, of course). Not so for the householder. As one person who has done several years of residential training and is now a single householder said, “I found I could stay in bed for the whole day and no one would even know about it.”

For many of us, householder practice is much more like hermit practice so creatively following the live vein of dharma inquiry is one vital way to establish spiritual security in the whirl of world.

Another important theme in householder life is service. A student recently talked about the power of letting go of his agenda for the moment and just being with his son who had fallen and hurt his back and was crying. Rather than “How can I get what I want?” the issue becomes “How to serve the truth of this moment?”

And finally, for the householder, faith is vital. Faith in the triple treasure of buddha, dharma, and sangha not only as a warm-hearted feeling of confidence and humility but as something we do.