Note: This is the first installment in a series of seven or eight that I call my koan confessions, although I confess that most of the confessions aren’t confessions in the usual sense.

Note: This is the first installment in a series of seven or eight that I call my koan confessions, although I confess that most of the confessions aren’t confessions in the usual sense.

I wrote the whole piece a few months ago upon request, although it doesn’t look like it’ll be used for it’s intended purpose so (desperate for fresh blog food), I’ll post it here, one confession at at time. The beginning has some introductory material that regular readers might already be familiar with, I suppose.

Recently I was talking with a friend, George Bowman, a successor of Dae Soen Sa Nim and a long-time student of Sazaki Roshi, both koan Zen teachers. We were sharing experiences with koans, including some of the persistent issues – what the traditional answers were in the various teaching lines, the weight to give to the traditional answers, and what really mattered after all.

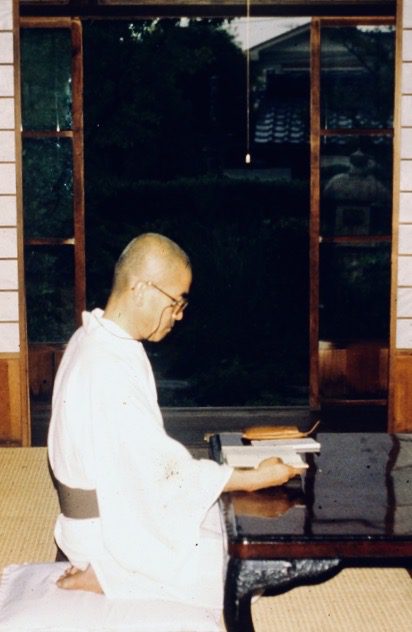

I had studied just-sitting Zen for thirty-odd years and had received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Roshi, one of the pioneer proponents of just-sitting Zen in the West. I’d taught for fifteen years, written a book and traveled some teaching just-sitting Zen.

Then several years ago, the opportunity had opened up to work the koan system with the three lovely Boundless Way Zen teachers, James Ford, Melissa Blacker and David Rynick. I was determined to put myself into koan training by my long-held hunch (based on a few thousand hours of Dogen study and intermittent koan dabbling) that koan and just-sitting Zen, despite sectarian stories to the contrary, were about the same so-called thing.

More importantly, I’d long been aware of a yearning in my heart to dig deeply into the process of koan introspection. The dang thing just called to me! So despite the fact that I was a teacher in the just-sitting school, I jumped at the opportunity.

George knew my story. “When you’re working with koan,” George asked, “do you feel that you are betraying your old teacher, Katagiri Roshi?”

Confession #1: No.

Koan Zen is a powerful process for disclosing the same truths that Katagiri Roshi taught. Although the old guy was incredibly devoted to the just-sitting way, he was really open to me experimenting with various aspects of the buddhadharma and this I’ve continue to do.

However, Katagiri Roshi did take on the sectarian conflict between the Japanese schools of just-sitting and koan Zen, Soto and Rinzai, a feud going back a few hundred years. Roshi wrongly thought that koan Zen was about getting some sweet candy. Despite taking sides, Roshi would also often lament, “Under the beautiful flag of religion, we fight.”

It is time to stop the in-family fighting between koan and just-sitting Zen, a feud that arose in historical circumstances long past and that we have no reason to replay in the blooming global culture of the buddhadharma. That doesn’t mean that I’m saying the koan Zen and just-sitting Zen are the same. Each method has it’s own processes with virtues and weaknesses and in this series I’ll share some of my opinions about these while I hope to avoid fighting under a beautiful flag.

I’ve found that koan training is an ingenious system of spiritual development aimed at the realization of our true nature, embodying the way and “don’t know mind” with elements that are in line with modern educational methods.

The Tibetan master Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche once observed with his characteristic searing insight that Zen is “the biggest joke that has ever been played in the spiritual realm. But it is a practical joke, very practical.”

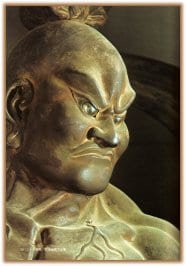

Hakuin, regarded as the founder of the modern koan system, had embedded both of these qualities – humor and pragmatics – into the koan process, in addition to emphasizing the importance of personally verifying the buddhadharma, also known as “kensho.” Although there are many possible dharma insights, Hakuin and his line of spiritual geniuses selected the most practical realization as the foundation of koan introspection, and for wholeheartly being who we are.

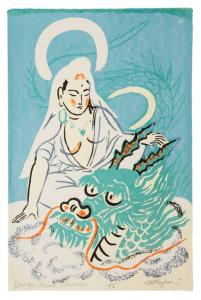

Some orthodox just-sitting Zen teachers regard koan Zen as misguided in that it focuses on an ugly and evil gaining idea called “kensho” (literally, “seeing true nature”). Rather than kensho, just-sitting advocates focus on practice-enlightenment – i.e., how can we actualize the fundamental point in each particular situation of daily life.