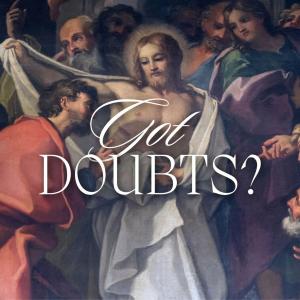

Throughout the summer, my wife — The Reverend Canon Natalie Van Kirk — and I have been preaching a series on the subject of doubt. We have been addressing both the subject of doubt itself and the questions that are often the source of trying questions for Christians, as well as others. Obviously, none of these articles are exhaustive but we hope that they will be a helpful stimulus to your own thinking.

Frederick writes:

1.Now the serpent was the most cunning of all the animals that the LORD God had made. The serpent asked the woman, “Did God really tell you not to eat from any of the trees in the garden?” 2.The woman answered the serpent: “We may eat of the fruit of the trees in the garden; 3.it is only about the fruit of the tree in the middle of the garden that God said, ‘You shall not eat it or even touch it, lest you die.'” 4.But the serpent said to the woman: “You certainly will not die! 5.No, God knows well that the moment you eat of it your eyes will be opened and you will be like gods who know what is good and what is bad.” 6.The woman saw that the tree was good for food, pleasing to the eyes, and desirable for gaining wisdom. So she took some of its fruit and ate it; and she also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate it. (Ge 3:1-6)

If are going to get clear about an answer to the question, “Does death get the last word?” We need to be clear about what “death” is. And there is no more dramatic and stunning picture of its operation in the world, than the one provided in Genesis three.

But, in order to understand what Genesis three has to tell us, first we need to know what the first three chapters of Genesis are all about. And I am going to be forced by the space available here to be both brief and direct about that issue, so that we can get to the subject at hand.

So – bear with me – the first three chapters of Genesis should not be read as history. And Adam and Eve are not historical figures. They are a myth – a story – written in the service of telling truths about God, the universe, and ourselves. And those truths are these:

- There is a God and you are not.

- That God made all that is and sustains it with his Spirit.

- But, unfortunately, we regularly try to be our own gods.

- And, when we do, death enters into the world.

Now, when we talk about death, we usually think about the end of life. We think of hearts stopping. We think of brain activity fading away. We think of funerals and graveyards.

But the story of Adam and Eve’s bid to be their own gods doesn’t end with of these things, even though God tells them they will die. So, what’s going on?

One can assume, that the serpent is right, and death really isn’t the consequence of their behavior. Or, one can assume that, because Adam and Eve eventually die, death (in the graveside version) is what God has in mind.

But that’s not the way that the story reads. Instead, the story records that in the wake of their disobedience, Adam and Eve clothe themselves. They blame one another for their separation from God. And then God tells them that a series of new miseries will become common features of their lives: the serpent and humankind will be enemies; pain will accompany childbearing; tensions will plague their relationships; the earth will not easily yield crops; thorns and thistles will be the norm; and labor will be a necessity.

The inference of the story, then, is that death enters into the world and the result isn’t just that human beings and the rest of creation expires at the end of life, but that death manifests itself in a hundred and one other ways. And what holds all of these intermediate and ultimate forms of death together is a loss of God’s presence and God-given purpose.

You see, up to this point, God has made Adam and Eve. He has declared them his vice-regents and he has left creation in their care: to name, to live in harmony with both God and God’s creation. That world flourishes, until Adam and Eve choose to be their own gods. But they do, the continuity of the breath of God which sustains the world is interrupted and connection with the purposes of God for the whole of creation life is disrupted.

Think of it this way, as long as God’s animating spirit fills our lives, whether one has in mind our bodies, our relationships, or our life’s work, we flourish and the power of death is held at bay. But when other purposes enter into the world, then our lives, our relationships, and our work disintegrate for lack of a God-given purpose.

Let me give you one example of the way in which death takes root in our daily lives: In the context of the sacrament of marriage, our sexuality has – as its purpose – and the expression of sacrificial love and, when possible, the procreation of children. It presupposes a love that – above all – is completely devoted to the healing, wholeness, and well being of another person on their journey into God. That purpose, that inner logic, is what holds a sacramental marriage together.

And while not all people marry and not all married people have children, the church celebrates that self-giving, self-sacrificial logic in the sacrament of Holy Matrimony. And it serves as a reminder to the church of Christ’s own self-sacrifice, which is why the church is often described as “the bride of Christ”.

If you take that God-given and holy purpose out of the experience of our sexuality, the god-given nature of our sexuality dies and the sacrament of marriage dies with it. Our sexuality can even become destructive and death-dealing.

Sexual exploitation, pornography, pedophilia are all manifestations of what Scripture describes as the power of death at work in the world. This is undoubtedly why the sexual revolution not only failed to make people happier but gave us a society in which people marry less often, have fewer children, and – ironically – even have less sex.

This is not to say that our society’s sexual practice before the sexual revolution was holy. It wasn’t. But because our social corrective was no better informed by God’s will for us than was the existing set of assumptions that governed our behavior, the entire enterprise ended in disaster.

I could multiply the examples of the ways in which death manifests itself in our world, long before we suffer the kind of death that involves funerals. Whenever a focus on the purposes of God and the life-giving Spirit of God is crowded out by that which is not of God, the result is always the same. It applies to the way in which we use our gifts and skills, our intellect, our capacity for invention and ingenuity. It applies to the way in which we use information and the ways in which we use wealth. It applies to our churches, our institutions and our governments.

True, some of these parts of our lives, especially our institutions and governments are a product of specific histories and social conventions and they aren’t God-given, as such. But we all know that they can be instruments of well-being that – even when they are not explicitly Christian – can still be turned to malevolent purposes.

But the point I want to make is that just as eternal life – life in the presence of Christ is a present tense as well as a future tense gift. So, also, death can be both a dimension of daily life, as well as life’s end. Because whenever the Spirit and purposes of God are missing, the world around us disintegrates and – as Genesis puts it – returns to dust.

Now, because we are surrounded by the influence of death in both daily and final ways, does that mean that death gets the last word? The answer of Scripture and the Christian tradition is a resounding “No!” And the foundation of that “No!” lies in the incarnation, life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus as the Son of God. Having entered into our lives and having conquered the power of death, Jesus has conquered the power of death which is now being reversed by his church, which is the body of Christ and which will be completed in his second Coming.

To use an analogy to our recent celebration of the 80th anniversary of D-Day, we have yet to celebrate the end of the war with death. But in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, God has landed on the beaches of our death-riddled world and the end of that struggle is inevitable.

In the meantime, however, Christ’s church is called to participate in that battle, using the two spiritual practices that shaped the life of Jesus: One is to seek God’s life-giving purpose in all that we do. The other is to be willing to embrace our own cross, which is the symbol of Christ’s self-sacrifice and enlivens every dimension of life.

This means that the mission of the church is to transform the world, by witnessing to Christ’s life-giving example. We do not do it in our own name or on our own power. We do not do it in the name of our own values or in the name of someone’s politics. We do it in Christ’s name. That means that we will need to be willing to embrace the task of sharing eternal life – God’s life – without always having allies in what we do as the body of Christ and without having the same reasons for what we do.

I can think of countless examples in the history of the church who believed that sharing the life of Christ transforms this life and the life to come. People who ventured out, without the approval of their friends, often without even the approval of the church.

William Wilberforce began his battle against the slave trade when he was the one and only person in England’s parliament that favored its abolition. Frances Cabrini began a mission in New York City to our country’s Italian immigrants without the approval of the bishop or the mayor of New York.

But the problem with examples of this kind is that it suggests that the only life-giving work we can do in the world has to be on a massive scale. There are two cautions I would offer about that reaction: One is that people like Wilberforce and Cabrini eventually had a global impact. Yet the work that they began was small and lonely, and they could not have foreseen the results. Never underestimate the life-giving potential of any effort, when you give yourself to Christ’s calling on your life. The other caution I would offer is this: Touching just one person is like touching the world. So, never allow the desire to do something grand obscure the importance of doing something meaningful.

Remember, instead, that Jesus conquered the power of death on our behalf, by doing the will of God and by embracing the cross. God’s keeping as you seek your own expression of that life-giving path.