Throughout the summer, my wife — The Reverend Canon Natalie Van Kirk — and I have been preaching a series on the subject of doubt. We have been addressing both the subject of doubt itself and the questions that are often the source of trying questions for Christians, as well as others. Obviously, none of these articles are exhaustive but we hope that they will be a helpful stimulus to your own thinking.

Frederick writes:

When I told friends that my wife and I were working on a series of articles on doubt and that I was going to speak to the question, “Is there a God?”, a number of them made comments that suggested that they were thinking, “Boy you really drew the short straw, didn’t you?” But the truth is, in a fit of insanity I actually volunteered to write a bit about the subject.

It could be that I made this foolhardy promise because of a childhood experience. The first washing machine that my parents ever owned was this giant metal tub with an big agitator in the middle that slowly went back and forth. Above it, on the back, were two large, hard rubber rollers. You put the clothes in between them after they were washed, a lever pressed the rollers together, and with a hand crank you rolled the clothes through them, pressing the water out, so that you could hang your clothes on the line outside to dry. Then you drained the remaining water from the tub into a hole in the basement floor.

As a result, my mother was stuck in one place dealing with this machine for hours. And that is where I sprang my first philosophical and theological question on her at the age of five: “How do we know God exists?” I’m sure my mother’s question was, “Why hasn’t God come up with something better than this damn machine?” She probably also thought, “What is it with this kid?” But those are both different philosophical problems.

I don’t remember exactly what my mother said but I have thought a lot about the existence of God off and on over the years. As with every other question Natalie and I are discussing, I don’t expect to “solve” the problem or give a “final answer” to the question. But I do want to offer some ways of thinking about it that I hope will be helpful.

The first thing to note is just how complex this question is and how much is at stake. Some people think that the existence of God is a big, abstract issue that has very little bearing on daily life – a bit like the question, “Is there life on other planets?” Unless aliens show up tomorrow afternoon the answer is likely to be of very little consequence.

But that isn’t the case with the existence of God. When we answer that question we are also answering other questions: Do our lives have meaning and purpose? Is there such a thing as right and wrong, justice and injustice? Do we do endure beyond the grave?

It is true, that without God you might be able to offer constructive answers to these questions. But the only reasons you could give for your answers would be utilitarian. In other words, you would be forced to say, “God doesn’t exist, so none of these questions can be answered positively in any sense that will outlive us or that is beyond us. But for the time being we should act like they do because life works best this way.”

One can’t talk about the inherent dignity of human beings, God-given rights, or in the language of the Declaration of Independence, “truths [we hold] to be self-evident”, because there would be no such truths. There would only be truths we live by, because things work more smoothly. And, of course, if there is no God, this also means that people who don’t live by those truths aren’t really wrong or immoral. They’ve just broken rules that a majority of people have agreed upon for the moment. This is why, then, that some people and countries regularly do things that are immoral and unjust.

So all of this – and much more – is at stake when we ask the question, “Does God exist?” But how do we answer the question itself?

First of all we need to be clear that the question of God can’t be answered in scientific terms. We cannot prove that God exists and – likewise – we cannot prove that God doesn’t exist.

This shouldn’t bother us. There are many truths about life that don’t submit to scientific proofs. Beauty, love, virtue, right, wrong, justice, injustice — all this and more lies at the heart of what we value most in life but proving that those values have an existence independent of our perceptions or beliefs is impossible.

What we can do is subject the question of God’s existence to a test of probability. Put in the form of a question, the test of probability asks, “Can the existence of human life and with it – the world around us, the concept of meaning, and notions of right and wrong – be better explained by the existence of God or by a natural process like evolution?”

You won’t be surprised to discover that I believe that the existence of God better explains us, our nature, and the world around us, than does evolution. But let me tell you a bit about why I do.

One reason has to do with the origin of anything at all.

My first, more detailed introduction to the theory of evolution was as a college freshman. My professor set out the process of evolution, arguing that it all began with the big bang – a highly concentrated, unique explosive event, that set the whole of the universe in motion.

The theory cannot offer any reason why this explosion took place or why it took place only once. But most significantly, it cannot explain where the matter and energy that made this explosion possible came from in the beginning.

This points to one of the limits of science itself. Science is an amazing, descriptive tool. It can describe what is and it can give an account of the processes that govern what already exists.

But it is not an effective explanatory tool. You cannot apply it to the moment when nothing existed and explain why something just appeared. In a vacuum where there is no matter, no forces or interactions, no energy present, science is necessarily silent. And when it is forced to pronounce on situations like that, it inevitably exceeds the strength of its tools.

Religion, on the other hand, offers those explains and can account for the existence of both matter and energy. And the unique characteristic of the Judaeo-Christian tradition is that it does this without excluding scientific explanations for the way in which the world evolved and works.

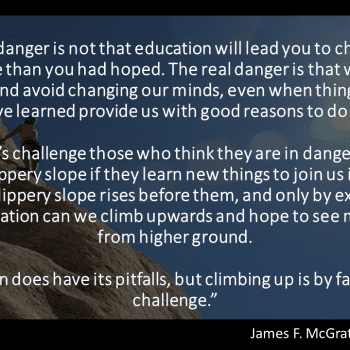

We may bristle at the conviction that we cannot explain everything and that there are limits to the knowledge a single discipline like science can offer. But humility has always been the key to great scholarship and a lack of it has almost always led to disaster.

The inherent complexity of creation is the second phenomenon that vindicates a belief in God.

Oxford mathematician, John Lennox, is also a Christian. He makes the observation that a large part of what prompted him to embrace the Christian faith is the fact the human mind can generate equations that help to describe the universe and the way in which it functions.

He notes that this is impossible to explain if one believes that a mindless, unguided process produced the human mind and made it possible for that mind to grasp the world around it. He notes that if anything, one would be bound to mistrust the human mind, if it arose out of a random process in an equally random world. As he notes, Albert Einstein often observed, “the only thing incomprehensible about the universe is that it’s comprehensible.”

Lennox observes that the only explanation possible is that a divine mind ordered both existence and the human mind. And that conviction he notes, is why the original pioneers of science all believed God: Galileo, Newton, Kepler, and those who laid the foundations of the scientific method, botany, modern optics; astronomy and physics; the theory of gravity and calculus; modern genetics; soil science; the theory of relativity; physiology; affective Computing; and the human genome project have all been shaped by Christians.

As C.S. Lewis noted, the great sciences have all been shaped by Christians who “expected to find laws in nature, because they believed in a divine legislator.”

Without God, the even more improbable result is our sense of morality.

As different as societies are and as much evil as there is in the world, the vast majority of human beings are convinced that there is right and wrong, justice and injustice. We may debate some of the particulars and our pursuit of the good and the just is less than perfect but without a divine mind or word at the heart of creation, it is very difficult to explain this phenomenon by arguing that it is a better way forward in evolutionary terms.

Even modern atheists like Brett Weinstein and Richard Dawkins have been arguing for the importance of cultural Christianity to the survival of western civilization. But they ignore the fact that it is only baptized Christians who make a moral understanding of our world a possibility.

And that observation brings me to a final point: The case for the probability that God exists will only take you so far, just as reason will take you so far in life.

Wrongly, atheists assume that the whole of life can be navigated with the help of science and reason. But anyone who has ever navigated the challenges of finding meaning and relationship in life has to know that if those are the only planes of perception that govern your life, you will fail at both. If you don’t believe me, try telling someone that you love that you love them for purely utilitarian reasons – or because evolution insists you pretend that you love someone. Good luck with that.

One of the conceits of the Enlightenment has been that reason can unlock every door, solve every problem, restore every relationship, heal every society. But the societies governed by that premise have been murderous and coercive: the French Revolution, Nazi Germany, the USSR, and Red China were all governed by one version of that premise or another – and they also claimed more lives in the process.

The fact of the matter is that there is another, important, and complementary plane of perception and until you enter into it wholeheartedly, you cannot understand its power. And that plane of perception can only be entered into through faith.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali was born in Somalia, she moved to Holland and then to the United States where she has served as a politician and human rights activist. She was also an outspoken atheist and was considered one of the leading voices for a secularist point of view – in particular because of her experience of fundamentalist Islam. But recently she became a Christian and her description of her conversion illustrates my point:

I didn’t, like many people who come to faith, see big banging lights. And I didn’t have any of those spectacular experiences that some people share. I wish I did, but I didn’t. I had a personal crisis. I lived for about a decade with intense depression and anxiety and self-loathing. I hit rock bottom, I went to a place where I actually didn’t want to live anymore, but wasn’t brave enough to take my own life. So I was self medicating. I had over a long period of time seen a psychiatrist, other doctors. I was trying to understand my condition and trying to treat it with the help of pure evidence-based science.

And in January, February of last year, I saw one therapist who said, perhaps it’s something else that you have. And she described it as spiritual bankruptcy. And that resonated with me. And having reached a place where I had absolutely nothing to lose, I prayed and I prayed desperately. And for me, that was a turning point. And what happened after that is a miracle in its own right. I feel connected to something higher and greater than myself, I feel I… my zest for life is back. And that and that experience has filled me with humility…

My friends, it is that journey into which Christ invites us.