Genesis 32:3-32; 33:1-11:

Jacob sent messengers before him to his brother Esau in the land of Seir, the country of Edom, instructing them, “Thus you shall say to my lord Esau: Thus says your servant Jacob, ‘I have lived with Laban as an alien and stayed until now, and I have oxen, donkeys, flocks, male and female slaves, and I have sent to tell my lord, in order that I may find favor in your sight.’ ”

The messengers returned to Jacob, saying, “We came to your brother Esau, and he is coming to meet you, and four hundred men are with him.” Then Jacob was greatly afraid and distressed, and he divided the people who were with him and the flocks and herds and camels into two companies, thinking, “If Esau comes to the one company and destroys it, then the company that is left will escape.”

And Jacob said, “O God of my father Abraham and God of my father Isaac, O Lord who said to me, ‘Return to your country and to your kindred, and I will do you good,’ I am not worthy of the least of all the steadfast love and all the faithfulness that you have shown to your servant, for with only my staff I crossed this Jordan, and now I have become two companies. Deliver me, please, from the hand of my brother, from the hand of Esau, for I am afraid of him; he may come and kill us all, the mothers with the children. Yet you have said, ‘I will surely do you good and make your offspring as the sand of the sea, which cannot be counted because of their number.’”

So he spent that night there, and from what he had with him he took a present for his brother Esau, two hundred female goats and twenty male goats, two hundred ewes and twenty rams, thirty milch camels and their colts, forty cows and ten bulls, twenty female donkeys and ten male donkeys. These he delivered into the hand of his servants, every drove by itself, and said to his servants, “Pass on ahead of me, and put a space between drove and drove.” He instructed the one in the lead, “When Esau my brother meets you and asks you, ‘To whom do you belong? Where are you going? And whose are these ahead of you?’ then you shall say, ‘They belong to your servant Jacob; they are a present sent to my lord Esau, and moreover he is behind us.’” He likewise instructed the second and the third and all who followed the droves, “You shall say the same thing to Esau when you meet him, and you shall say, ‘Moreover your servant Jacob is behind us.’” For he thought, “I may appease him with the present that goes ahead of me, and afterwards I shall see his face; perhaps he will accept me.” So the present passed on ahead of him, and he himself spent that night in the camp. The same night he got up and took his two wives, his two maids, and his eleven children and crossed the ford of the Jabbok. He took them and sent them across the stream, and likewise everything that he had.

Jacob was left alone, and a man wrestled with him until daybreak. When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he struck him on the hip socket, and Jacob’s hip was put out of joint as he wrestled with him. Then he said, “Let me go, for the day is breaking.” But Jacob said, “I will not let you go, unless you bless me.” So he said to him, “What is your name?” And he said, “Jacob.” Then the man said, “You shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with humans and have prevailed.” Then Jacob asked him, “Please tell me your name.” But he said, “Why is it that you ask my name?” And there he blessed him. So Jacob called the place Peniel, saying, “For I have seen God face to face, yet my life is preserved.” The sun rose upon him as he passed Penuel, limping because of his hip. Therefore to this day the Israelites do not eat the thigh muscle that is on the hip socket, because he struck Jacob on the hip socket at the thigh muscle.

Now Jacob looked up and saw Esau coming, and four hundred men with him. So he divided the children among Leah and Rachel and the two maids. He put the maids with their children in front, then Leah with her children, and Rachel and Joseph last of all. He himself went on ahead of them, bowing himself to the ground seven times, until he came near his brother.

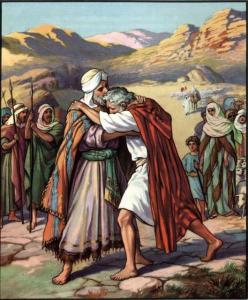

But Esau ran to meet him and embraced him and fell on his neck and kissed him, and they wept. When Esau looked up and saw the women and children, he said, “Who are these with you?” Jacob said, “The children whom God has graciously given your servant.” Then the maids drew near, they and their children, and bowed down; Leah likewise and her children drew near and bowed down; and finally Joseph and Rachel drew near, and they bowed down. Esau said, “What do you mean by all this company that I met?” Jacob answered, “To find favor with my lord.” But Esau said, “I have enough, my brother; keep what you have for yourself.” Jacob said, “No, please; if I find favor with you, then accept my present from my hand, for truly to see your face is like seeing the face of God, since you have received me with such favor. Please accept my gift that is brought to you, because God has dealt graciously with me and because I have everything I want.” So he urged him, and he took it.

One Sunday on the way out to the car, my wife, who is Rector of the church that I serve, informed me that one of the boys in our children’s program, whose name is EJ, launched his brother Beau off of a swing. The boys had tried this experiment before. The thrill of throwing another boy into space explains a lot of things about male behavior.

The boys had been cautioned to stop doing this but – as is often the case – the parental advisory was lost in the mix of things. And they gave it another go.

Unfortunately, this time the trajectory was a bit high and a smooth reentry to sustain. And as a result, Beau has a cast, which he proudly showed my wife.

I confess, my response was typically male and unfiltered. When she told me that EJ had launched Beau off the swing, my reaction was, “Of course he did. What good is a brother, if you can’t launch him into the atmosphere?”

There is a childhood precedent for this attitude in my own up-bringing. When, my brother and I were young, we theorized that galvanized buckets had a striking resemblance to the helmets worn by knights in shining armor. And having donned one each, we had great fun banging one another in the head with sticks. We didn’t calculate, however, for the lack of a visor and I lost my footing near a window well outside the basement and fell into it, shattering the window. I have a small scar as a result, that could be explained by referring to something more exotic but honesty is the best policy. To paraphrase an unknown wit, “I won’t let my brother do anything stupid… alone.”

I mention this pattern because it is easy to assume that their relationship is without parallels in modern experience. And there certainly are cultural differences. But the truth is that we are all shaped by our relationship with brothers and sisters. And our childhood experiences can shape us deep into adulthood, whether we acknowledge the power of those relationships or not.

So the story of Jacob and Esau has implications for us, even if some of the features of that relationship belong to a different time and culture. The invitation, then, this morning is to reflect on their story and its relevance for us — not as an artifact of the past but as a window into our own lives.

To do that, let me remind you of the background to this passage from Genesis:

As we noted earlier in the series, Esau and Jacob were twins. Esau, born just ahead of Jacob, was a hairy baby, hence the meaning of the name, Esau. By nature he was a hunter and a guy who lived by his gut (as the expression goes). Nothing mattered more than the moment.

Jacob, by contrast, lived by his wits and – often by deception – hence, his name, “the heel grabber”. A name that not only described what he was doing to Esau when they were born but a perfect metaphor for the way in which he negotiated life.

These differences shaped their relationship and – one day – preoccupied with satisfying his hunger, Esau rejected his birthright in favor of a bowl of lentil soup offered to him by Jacob. The Hebrew actually means, “spurned” or “threw away”. We have talked about the way in which Jacob took advantage of his brother. But Esau was overcome by nothing more than a few hunger pangs and an over-developed sense of the dramatic. So, viewed from another angle, the two brothers were on a collision course and both of them made huge mistakes.

So, what we have in this ancient story is the description of two siblings, with the same parents, a negligible difference in birth order, and very different personalities that lead them into a conflict that shaped them for a lifetime. That never happens in the modern world, right?

As the story goes, this conflict was so intense that Jacob fled and the Book of Genesis focuses on Jacob. But chapters 32 and 33 bring his broken relationship with Esau back into focus. Jacob has had enough of living in his father-in-law’s home, and decides to move. But this will bring him back into physical proximity to his brother and – always calculating – he tries to buy a reconciliation with Esau: “‘I have lived with Laban as an alien and stayed until now, and I have oxen, donkeys, flocks, male and female slaves, and I have sent to tell my lord, in order that I may find favor in your sight.’ ”

There are three things to consider here: One, as the therapists in the congregation will tell you, moving will occasionally ameliorate a problem, but geography is rarely a cure-all. By running away Jacob avoided getting killed on the spot, and it gave him twenty years to consolidate his fortunes. But the rift with Esau remained and if you think today’s world is small, we can’t imagine how small their world was.

Two, wherever we go, there we are. For Jacob, life is all about calculations, planning and manipulation. So, the king of the pre-mortem he anticipates the problem that moving will pose and he tries to neutralize Esau’s anger.

And, three – thank you, Paul McCartney – money can’t buy you love. The psychology of this ancient story is all there. Jacob the heel grabber can’t help himself. His own life has been about cutting corners and finding leverage; and – after all these years – he assumes that others are motivated by the same values that motivate him. Nothing in his experience had forced him to do any self-examination – not running away from home, not even Laban beating him at his own game had humbled him. And, after all this time, he assumes he can buy peace with Esau.

And how Esau respond? Esau, the man of action, the man who lives by his gut and who – with Yogi Berra — would probably have said, “Forget the past, just not the grudges”? The text of Genesis puts it flatly, leaving us to draw our own conclusions, just as Jacob did: “The messengers returned to Jacob, saying, ‘We came to your brother Esau, and he is coming to meet you, and four hundred men are with him.’ Then Jacob was greatly afraid and distressed…”

The commentaries on this passage can be astoundingly silly. Leave it to biblical scholars to debate whether these 400 men were armed. First, no one traveled unarmed across the trans-Jordan and there is even less point in traveling with 400 unarmed men. Second, 400 was a typical number of men assigned to a regiment or raiding party. They were hardly there for the fellowship of it. And, if an unarmed posse was a possibility, why describe Jacob as “greatly afraid and distressed” or offer the prayer for deliverance that follows? The fact of the matter is that Jacob drew the only conclusion that the realities and a guilty conscience would allow him to draw.

In spite of this, he continues to explore the possibility of buying his brother’s love – or, at least a commitment to peaceful coexistence. So, Jacob sends the promised gift of goats, two hundred ewes, rams, camels, cows, bulls, and donkeys.

What strikes many as inexplicable is the passage that follows. At first glance, Jacob’s wrestling match with an unidentified man feels like a non-sequitur. What does this encounter have to do with anything? And the story is so powerful that it is often read and discussed without any context.

But if one takes the story up to this point seriously, it is clear that this experience is part dream, part vision, and part panic attack. Jacob has burned his bridges with Laban. Everything that lies ahead depends upon his relationship with his brother and it looks like he will lose his life. And now the heel grabber finds himself in a literal wresting match.

Asking whether this experience was “real” is an emotionally naïve question to ask. Of course it was and it left its mark, physically and spiritually. Commentators differ on who the mysterious man is, but Jacob is in no doubt: “I have seen God face to face, yet my life is preserved.” And the outcome is a blessing and new name, Israel, which means “one who struggles”.

It only becomes clear what has happened the following day. He approaches his brother, bowing seven times and calling him lord (or “honored one”), and when Esau declines the gifts he has offered, Jacob-now-Israel responds, “No, please; if I find favor with you, then accept my present from my hand, for truly to see your face is like seeing the face of God, since you have received me with such favor. Please accept my gift that is brought to you, because God has dealt graciously with me and because I have everything I want.”

The man who wanted everything that his brother had and cheated to obtain it has at last found the blessing that God had longed to give him all along. And in laying down his desire to be his own god, he has been reconciled with both God and his brother.

It is worth noting that in the healing that takes place, Esau receives what God has longed to give him as well. The blessing he lost is returned to him. His heart is filled with love and – acting out of the redeemed version of his own heart, his resolve to kill his brother dissolves, and he falls on Jacob’s neck, and embraces him.

This remains to be said: The stories of Genesis echo and repeat themes that are outlined in its opening chapters and that is the case here, as well. As in the case of Cain and Abel, we have yet another story of brothers. And the well-being of their relationship depends upon their relationship with God. In the case of Cain and Abel, there is no healing and his jealousy spins out of control, ending in murder. In the case of Israel and Esau, healing only comes after Jacob exhausts his efforts to wrestle control of his own life away from God and surrenders to God’s love.

This pattern points to a central truth about ourselves and about the work of God in our lives. The dual command to love God with all our heart, mind, and strength and to love our neighbors as ourselves mirrors the healing work of God. We tend to think of these relationships as discreet dimensions of life – one spiritual, the other relational. But the truth is that we cannot fully understand the grandeur and sanctity of our neighbor’s life, until we see the image of God in him or her. And we cannot truly love God, until we see our neighbors as those graced with his image.

If you wonder whether your love of God means enough to you, you need only ask whether God’s love is enough for you. And if you wonder whether you have received everything that God longs to give you, you need only ask whether you are willing to see the image of God in the face of those you are inclined to despise. Like Jacob, we are likely to find the obstacles to answering those questions in the affirmative lies within ourselves. And those answers will not change until we wrestle with those obstacles in God’s presence. That is the nature of life for those who claim Israel as the father of their faith.