This last weekend marked the tenth anniversary of my younger brother’s death. He was a husband, father, and gifted orthopedic hand surgeon, whose life was defined by exacting skill in the name of compassionate care. An aggressive brain tumor and, ultimately, a devastating fall claimed first his career and then his life.

I don’t believe that such tragic losses are God’s will for us. I do believe that as we place our lives back into God’s hands on such occasions, God begins to beat back the power of death, which is decisively broken in the Resurrection. In my own grief and in an effort to reclaim some small measure of my brother’s loss, I wrote a book entitled, The Dave Test: A Raw Look at Real Faith in Hard Times. Had it not been for my publisher’s sensibilities, it would have been entitled, When Life Sucks, and the first chapter retains that language, buried behind the cover. (I suggested we sell them in paper bags, but to no avail.)

The book is based upon the conviction that to navigate losses of this kind and to walk alongside of others when they suffer requires an affirmative answer to ten questions:

Can I say, “life sucks?”

Can I give up my broken gods?

Can I avoid using stained glass language?

Can I admit that some things will never get better?

Can I give up trading in magic and superstition?

Can I stop blowing smoke?

Can I say something that helps?

Can I grieve with others?

Can I walk wounded?

Can I be a friend?

My brother knew people who could say, “yes”, to those questions and acted accordingly. He also knew people who could not, and they made his journey harder. The difference marks the sharp divide between those who can be vulnerable to the losses of others and those who cannot. The Dave Test is an effort to alert people to the difference and invite an honest, faith-full path forward.

A part of that journey involves telling our own stories. I am convinced that there is an irreducibly autobiographical character to our suffering as human beings. This precludes being able to say in any absolute sense that we “know” what someone else is experiencing. But I do believe that being candid and honest with one another about our experiences – in the right place and time – can whittle away at the darkness and isolation that we all experience.

In that spirit, then, I offer these thoughts from the postscript to the book. My prayer is that through them, you might find the embrace of God in those places that are often unspeakably hard but not without hope:

Monday, January 21, 2013

This morning at 2:00am, I stood by Dave’s hospital bed and held his hand as he died. We were all there: Dave’s wife, Belinda, his sons Michael and Eric, Michael’s wife Beth, and my wife, Natalie. We watched and wept as first his respiration failed and then his heart. None of us had expected to be saying good-bye to Dave so soon.

When that last struggle was past we kissed him, told him good-bye one last time and, finally, when we could avoid leaving no longer, we left. That night I said my last good-bye to my “little” brother.

On Wednesday, January 16, 2013, Dave went to the basement of his home to get a bit of fruit for dinner. None of us could have imagined how perilous that exercise of basic independence would prove to be. He made it down the steps, retrieved the fruit that he needed, and made his way back up the steps.

Somewhere along the way he tripped, suffered a seizure, or had a stroke. We will never know for sure what caused him to fall. What we do know is that he fell back down the steps, unable to break or slow his fall. His head struck the concrete floor behind him with so much force that the impact fractured his skull in several places, causing massive internal bleeding.

The team that cared for him that night took him to the Trauma Center at Vanderbilt University Hospital where the physicians and nurses did what they could to make him comfortable. After hours of silence, he rallied slightly on Friday, January 18.

He was aware that we were there. He responded to simple commands, squeezed our hands, gave us a thumbs-up sign, and smiled as much as anyone can smile around a ventilator. When they finally took out the ventilator he could even say a few words.

“I love you, Dave.”

“Love you too, Fred.”

“How are you doing, buddy?”

“I’m a wreck.”

In classic OCD style, he even cautioned his wife and son to “be careful out there,” as if there were any threat to compare with the one that swirled around him on that day.

But, in truth, the communication was fragmentary, disjointed, and brief. He could barely keep his eyes open and none of the comments he made lasted long or were related to one another.

As his condition deteriorated late on Friday and still further on Saturday the 19th he communicated with less and less frequency. His eyes remained firmly closed as if he was trying to muster the same inner strength that had brought him through two surgeries to remove parts of his brain. As though, with enough concentration he could find his way out of this terrible place.

On Saturday, the words disappeared and instead he mumbled incoherently. What we thought we heard him say that day probably had more to do with what we hoped to hear him say, than it did with what he might have been trying to say at all.

A long conversation with his physicians early on Sunday the 20th led us to conclude that there was little hope of finding a comfortable, independent window of life between the countervailing challenges of his injury and the vagaries of his cancer. It was a long weekend of trying to be sure we weren’t giving up and that we weren’t clinging to a life Dave would not have wanted to live.

The decisions we made that day were very hard to make. We are all mortal. None of us lives forever and we’ve known from the beginning that Dave’s cancer was a death sentence. But loss is love’s traveling companion and to love deeply is to be hurt deeply.

Dave’s own capacity for battling back also made it difficult to believe that he would not fight back again. He had two surgeries that I thought would condemn him to a largely sedentary life. Instead he sailed through them, as if to say, “Well that was a really unpleasant 48 hours. Let’s get living again.” In fact, just a week before his accident he bounced back from a grand mal seizure that prompted one of his close friends to declare, “He’s f—–g Lazarus.” It’s an adjective I’ve never heard used in that connection, but it seemed to fit.

The Lazarus story is not a resurrection story, however, and this time even Dave’s body seemed to be giving up the fight. So, we opted for hospice care and made arrangements to return him to his professional “home” at St. Thomas Hospital where he worked as a surgeon. There he could be surrounded by the friends and colleagues who had worked alongside of him in helping others seven years ago before the cancer took his career.

The choice was one that accorded with Dave’s wishes — one we hoped would make it possible for him to die with a measure of dignity that would match the courage he had mustered to live his life — one that subordinated our needs to his — and one that trusted in authentic ways in the promise of the Resurrection.

That trip “home” was not to be.

At 12:30am on Monday the 21st the nursing staff at Vanderbilt called to let us know that his breathing had changed and that there was not much time left. We drove to the hospital, sat with him through the little time that remained, held his hand, kissed his forehead, reminded him of our love, and prayed. At 2:05am he was gone.

Life is a journey of love and relationships. Caring for one another when life is hard strains and tests those relationships. We are easily tempted to run from its challenges — out of fear, out of selfishness, out of a sense of inadequacy. To run from those hard places is to run from life itself.

Belinda and the boys had counted on more time with Dave. They wanted him there as husband and father. He was the anchor in their world. He had so wanted to see Eric graduate from medical school, to see Michael and Beth’s first child.

I wanted him to be around, too. He was my brother. Our closeness had come too late in life and I was as greedy as anyone for every minute.

What’s more, I had just written the first two chapters of The Dave Test and I was counting on his approval of the rest. He had read the completed chapters and said that they were true and honest. He did wonder if my editor would really let me say some of that stuff. I had been looking forward to having his responses on the rest of the book. I knew he would tell me when I was blowing smoke, using stained glass language, or was just plain full of it. I hope the remaining chapters have been as true and honest in Dave’s eyes as the first two.

Dave and I talked twice a day for seven years — once in the morning, once in the evening. The hardest part of the days, weeks, months, and years ahead will be the silence.

Still, there is more than one kind of conversation and love is not dependent upon the tangible and conventional forms of it that we normally associate with it. That does not mean that I believe Dave is alive, because “he lives on in my heart.” He does live in my heart. He also lives on in Cliff’s heart and in Bob’s, in the lives of his sons and his wife, in the lives of those he touched and treated. But he is unrecoverably gone. His body will lay at Middle Tennessee State Veterans Cemetery. His spirit is with his Lord.

One day, however, we will all be gone. And if all if we could rely upon were our memories of one another, then love and relationships would be a fragile gesture in a cold, endless vacuum. Love lives on because God wins and death cannot, because the Resurrection is not a metaphor for a “spiritual” transformation, but God’s “no” to the counterclaims of death and decay.

I am blessed to have shared this journey with Dave. I love him, I am proud of him, and the grave cannot separate us. For that, I am utterly dependent upon the One who loves us both and grateful in ways that escape expression.

But, oh, how I miss him.

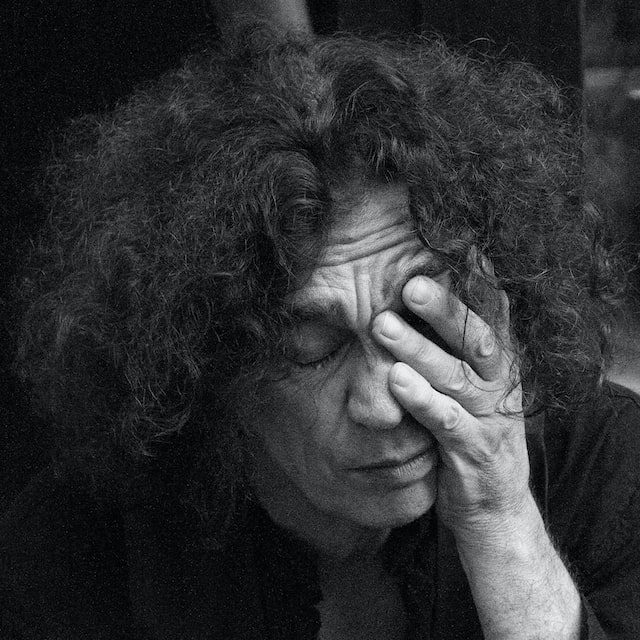

Photo by brut carniollus on Unsplash