The Nicene Creed was first adopted in 325AD and it has been at the heart of Christian worship and self-understanding for centuries. The word, creed, is based upon the Latin word, credo, which means “I believe”. But the Nicene Creed is more than a statement of beliefs. It is a series of convictions that can only be understood by living out their implications

This morning we will focus on the opening lives of the Creed focus on God as Father and Creator:

We believe in one God,

the Father, the Almighty,

maker of heaven and earth,

of all that is, seen and unseen.

Here, I focus on the conviction that God is creator.

In the ancient world, the question of whether god – in some form – had created the world was never at issue. In fact, before the Greeks came along, the creation of matter wasn’t so much the issue, as was the way in which matter was ordered and shaped. That said, the role of the divine was never doubt. The real debate between cultures was the question about whose deity got credit for creation. It is not surprising, then, to discover that the first chapter of Genesis doesn’t provide a proof for the existence of God, nor does it offer an engineering report on what God did and when.

Writing in a world where the gods of other cultures are associated with various features and forces of creation, the writer of Genesis is reminding his readers that their God – the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob – made the gods of other religions. Read as such, what the writer of Genesis is saying: “On the first day, my God created your god and your god and on the second day my God created your god and your god.” And so on. His point? “Your gods are not God.”

If Christians and others were clear about what Genesis is and isn’t saying, we could avoid misplaced, if not silly debates over the creation narratives. No, Genesis does not claim that the world and the universe were created in seven days – no matter how you define the word, day. No, believing that God created the world does not preclude a belief in the “big bang” (which – by the way – was a theory developed by a Christian monk); evolution which was developed by a theist; a solar system with the sun at its center (which was first established by a canon of the Catholic church); or a round earth (which people have believed since at least 500 BC).

That clarity would also keep people from insisting that science take the place of religion. Science is a powerful descriptive tool, and it can make judgments about things that exist, the patterns that shape their interactions, their make-up, and the way in which they act upon one another. What science can’t do is explain why anything at all exists. And, when it does, the people who make those assertions are exercising their faith just as much as anyone who believes in God.

What Genesis does argue is that:

The God is the creator.

That the natural order is his work and reflects his character.

And that creation is good, but it is not God.

Now, those three assertions are important all on their own. But their implications are wide-ranging and that is why they are echoed in the opening lines of the Nicene Creed.

First, they inoculate us against the dangerous assumption that we are our own gods.

On the face of it, that seems like a silly assumption. Gods don’t get Covid, need hospitals, and end up in cemeteries. But we still persist in acting like we are.

We lord it over our neighbors. We argue that we can make our own decisions without the help of others. We are convinced that we can craft our own identity. On more than one occasion, we have thought that we did – or could – put an end to war, poverty, slavery, murder, and mayhem. And we are convinced that our technology is somehow the same thing as wisdom.

Dorothy Sayers named this tendency decades ago. She called it the Creed of St. Euthanasia (listen to what she says):

I believe in man, maker of himself and inventor of all science. And in myself, his manifestation, and captain of my psyche; and that I should not suffer anything painful or unpleasant.

And in a vague, evolving deity, the future-begotten child of man; conceived by the spirit of progress, born of emergent variants; who shall kick down the ladder by which he rose and tell history to go to hell.

Who shall someday take off from earth and be jet-propelled into the heavens; and sit exalted above all worlds, man the master almighty.

And I believe in the spirit of progress…in a modern, administrative, ethical, and social organization; in the isolation of saints, the treatment of complexes, joy through health, and destruction of the body by cremation (with music while it burns), and then I’ve had it.

By contrast, the Nicene Creed reminds us that this is dangerous hubris. To acknowledge that God is Father and creator does not mean that we should not work for the well-being of our neighbors and the world (I will come back to that in a moment), but it does mean that if we think that we are free to do what we want to do and that we are masters of our own destiny, then our lives will end in tragedy. And this does not just happen on a big, societal scale, it happens daily on the personal level as well.

With variations, the composite story of some of my dearest and oldest friends goes something like this: They were born gifted. They went to university – where it was even easy to hide what they were really doing – especially the drugs and alcohol. Thanks to grade inflation and the anonymity of a big campus, they got further confirmation that they were in charge. Ditto graduate school, where in some cases they were even treated like gods.

Roll the clock forward and three or four marriages later, they ended up with a drug problem that they could no longer hide. At that point, they finally did a stint in rehab. Dried out, sobered up or went through detox, and there the first three things they learned were: You are powerless. Only a power greater than you can restore you to sanity. And it is time to turn your life over to God.

That’s a hard lesson to learn, when it takes twenty, thirty, forty, or even fifty years to learn. The church offers that wisdom, up-front, in the Creed, at our baptism.

But the description of God as Father and Creator is not at the beginning of the Nicene Creed just to remind us that we are not God. It is there to remind us, as well, that God – as creator – has expectations and desires for his creation that he will see fulfilled, whether we cooperate with them or not.

These are, again, convictions that are as old as Genesis. But they revolutionized our attitudes toward one another and creation itself over two millennia.

The story of Adam and Eve – which need not be historical to be true – underlines the fact that regardless of sex, race, nationality, age, social status, or the state of our bodies and minds, we are all made in the image of God. Our Declaration of Independence suggests that this is self-evident, but it is not.

It never has been and is not now self-evident. In the twenty-first century alone, forty million people have been enslaved. More than a million Muslims have been sent to concentration) camps, and Vladimir Putin has launched a war of carnage in which almost fifty thousand people have been killed, wounded, or are missing.

The Creed teaches us that this kind of behavior is evil. It also obliges us to oppose it and to do far better in our own lives. Our moral duty is not just to avoid such soul-destroying behavior, it is to act in ways that honor and help people to live into the realization that they are made in the image of God.

That task may sound grand and abstract, but it is not. We all know that in our interactions with one another, we can all name moments when we were encouraged, felt the love of God, and found hope. We can also identify times when the way that we have been treated left us angry, depressed, or isolated.

Small encounters – a handful of words, a loving gesture – these have a way of making God’s presence in the world tangible and real. Behavior that is demeaning and abusive do the opposite. So, in ways both large and small, we have the power to add more of one or the other to the lives of those around us.

That layer of care and attention extends to creation as a whole – not that the earth is made in God’s image – but because it is God’s good gift, and we have a profound responsibility for it. Some people shy away from the story of God putting Adam and Eve in charge of creation, because they think that the language in Genesis authorizes us to plunder the natural world and abuse it.

Nothing could be further from the truth. The language and images of Genesis are one of stewardship. We are not the rulers of creation, we are God’s vice-regents. And vice-regents are not empowered to do whatever they want to do. Vice-regents act on the king’s behalf and can only behave as the king would behave.

Here, too, we have opportunities very nearly every day to live out of the conviction that God is creator. We can honor creation in the way that we use its resources – not just by avoiding waste – but by using creation in ways that honor it. We can recover the spiritual roots of what it means to be a craftsman or the inspiration behind phrases like “animal husbandry”. Gardeners can share in the oldest of human undertakings. Builders participate in the craft of Joseph and Jesus. Singers and musicians participate in creative efforts that are older than the psalms. Engineers of all kinds amplify the dynamics of nature to shelter and protect us, to provide spaces for study, conversation, and fellowship. And cooks honor God’s good gift of food that others have harvested when they prepare it with care and attention. We can also recover what it means to be parents, grandparents, and mentors. Bearing children and raising them in the faith participates more immediately in the image of God than perhaps any other dimension of human life. The lifelong partnership between generations should engage all of us, whether we care for our own children or teach, guide, and encourage the children of others.

Back of it all, this truth is one which we should all remember: Clergy are not the only people who have a vocation in God’s creation. We all have a vocation, and we are all deeply dependent upon one another in making God’s will as creator a reality for us.

May you live in the light of that God who is both Father and Creator, now and forever. Amen.

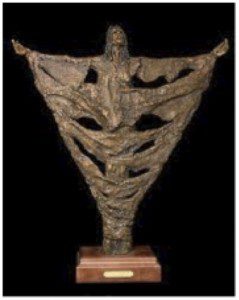

The photo is of Frederick Hart’s Ex Nihilo at Washington National Cathedral