Years ago, serving on the senior administrative team of a major seminary, we were pressed by the dean to give him “numbers”. What he meant by this was clear in the context. The seminary was struggling to keep pace enrollment-wise, and he had decided that the solution was to push program directors to promise certain enrollment goals for each of the areas for which we had oversight.

It was clear to me from the outset that this was both ill-advised and dangerous for each of us on the team. Plainly, we were going to be held accountable for those goals. And, yet, we had no reliable data to help us set those goals and – because enrollment and recruiting is centralized – we lacked the support staff to achieve them.

I chose not to play, knowing that the minute I made any promises, I was obliged to fulfill them, and I knew that I had no way of delivering on the promise. Instead, I offered a fairly comprehensive description of the obstacles that we faced in addressing the challenge that we faced:

- I noted that seminaries had made financial commitments that were unsustainable,

- That we had incurred too much debt

- That we had too large a faculty

- That seminary educations left clergy staffed with debt that they could not afford to repay,

- That we offered nothing online and nothing in the evening to students who were often holding down full-time jobs,

- And that the decline in enrollment could be traced to the changing demographics in the larger population.

This last point required a bit of explanation, but it was obvious to anyone who had been paying attention. Seminaries had expanded and proliferated based on the student demographics of the fifties, sixties, seventies, and eighties. Over those four decades, seminaries had benefited from the GI Bill and the return of veterans from both the Second World War and the Korean War. They had benefited again during the war in Vietnam as a fairly substantial number of students concluded that God, not the Selective Service, was calling them into ministry. Those trends had barely faded away as churches began to ordain women, and that trend not only increased seminary enrollments, but changed the constituencies of most seminaries. And, as that trend began to plateau at roughly 50% or more of the seminary student body, second vocation boomers began applying.

But, as I noted, those trends were largely exhausted in the nineties and there was nothing about the demographics or patterns of socialization that suggested there was anything else in the offing that would keep the seminaries afloat. Add to that the fracturing of major Protestant denominations and the shrinking number of people attending church, it was clear where we were headed.

When I finished, the Dean “complimented” me on my analysis and then observed, “But we don’t have time to be strategic.” That’s when I knew we were in trouble and it only came as a bit of a surprise that the following year the school began making staff cuts, the first of which involved eliminating the director of spiritual life and formation and folding it into the work of another member of the faculty.

This was all before the fracturing of still other denominations began in earnest. It preceded the creation of new pathways to preparation for ordination that do not entail getting a traditional seminary degree.[i] And, of course, no one could have anticipated the impact that Covid-19 has had.

The results have been predictable:

- Seminaries have been mothballed or merged with other schools.

- Others are represented by as little as a faculty member or two at seminaries that are holding on.

- For the first time that I can recall, seminaries are offering early retirement “deals” to older faculty members.

- And seminaries have experimented with a variety of other cost-saving measures – renting or selling space in their buildings.

- (Strangely, the one thing that seminaries don’t seem to be doing is shrinking the number of administrative appointments that they make.)[ii]

In the meantime, seminaries are working hard to reposition themselves: They are offering more two-year master’s degrees. They are shrinking the number of hours required for the Masters of Divinity; and they have begun repackaging all their degree programs, promising that they are not just for clergy, but will work equally well for a variety of other vocational undertakings, including community organizing and a variety of other, even more amorphous goals. In the meantime, most seminaries continue to produce PhDs, even as the programs that prepare them erode and disappear. And the Doctor of Ministry degree continues to provide a steady stream of students, hoping to enhance their ministry, providing seminaries with an opportunity to extract a last bit of value from their association with the church.

From the student’s point of view, this last set of strategies are perhaps the most problematic, because they touch on the quality of the education that the student receives and its value to them over a lifetime. For example: A Masters of Divinity that is modified to address the needs of students with a variety of vocational goals is, by definition, less useful to any one population. Courses in preaching and pastoral care, as a case in point, are essential to would-be clergy. They are largely irrelevant to a community organizer. A community organizer is, frankly, better off with a degree in public policy, non-profit management, political science, or economics. Given the secular orientation of most public policy organizations, a degree from a seminary is not only largely irrelevant to a prospective employer, it can actually be a liability.

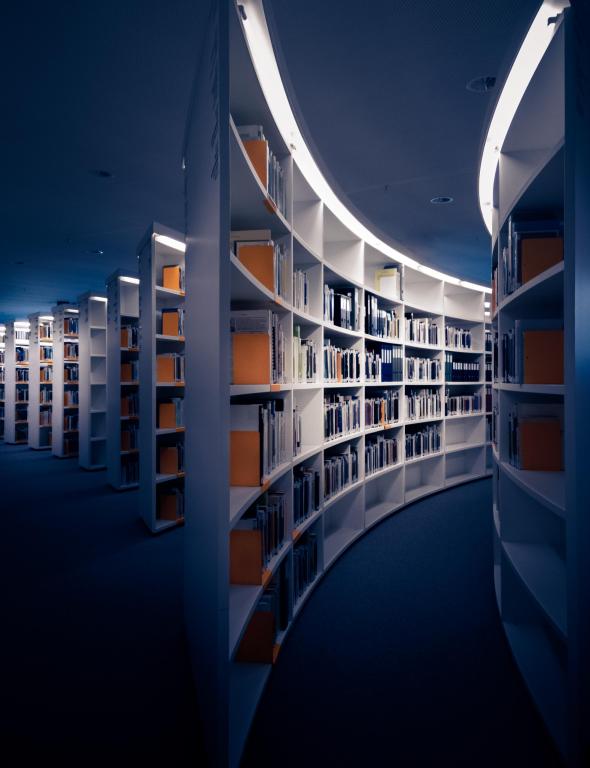

So, what lies ahead for seminaries? The future is complicated to say the least. If denominational seminaries were centralized, it would make sense to develop a strategic plan that governed their future collectively. Institutions, their faculties, libraries, and facilities could be consolidated, and most denominations could insure that regionally the needs of students were met. But each seminary has a different history, their own governing boards, and discreet budgets. So, their fortunes are in the hands of a Darwinian process that will continue to thin their ranks.

This means that seminaries are also far less likely to be entirely forthcoming about the weaknesses of their programs or candid about their viability. As strange as it may seem, then, prospective students will need to observe the tried and true maxim, “caveat emptor” or “buyer beware”.

Students should scrutinize programs, drill down and look at the course work that they will actually be expected to do. They should look to see how well the programs are supported by full-time faculty. They should beware of sweeping promises regarding the applicability of the degree program for which they are applying, and they should try to push for information regarding the success that the schools have in placing their graduates. They should cross-examine admissions staff regarding the availability of financial aid. And they should look at the ratings that schools receive.

They should also establish which schools their denominations rely upon and discover – if possible – which schools have been more or less successful in building a reputation for excellence. If the schools make sweeping promises about the non-traditional opportunities that their degrees will make available, press even harder and investigate whether those jobs exist and whether those schools are actually able to place them. Check, too, to see if other degrees and other kinds of institutions are favored by the employers you are considering. You can always pursue your theological interests on the side.

Finally, and this may sound cynical and if does, so be it: Whatever you do, resist the siren call of community and the chummy, “we are all just one happy family” language that has become so much a part of recruitment efforts. That is not true and, more often than not, cannot be true.

Unless it is required, students rarely attend chapel. With rare exceptions, seminary faculty do not spend all that much time with one another socially. The student body of most seminaries are over-committed at school, at home, and at work. As a result, seminary educations are often acquired under a fair amount of duress.

In short: It is a mistake to think of seminaries as churches, never mind the leading edge of a new social order. They are a place to get an education – or not – and you should treat them as such.

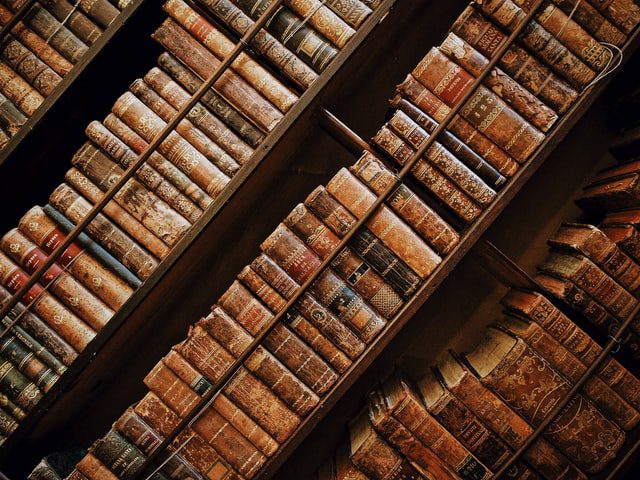

It is important to nurture, deepen, and strengthen your life in Christ. Cultivate a life of prayer, sharpen your convictions about the work of God’s grace, test your profession of the faith against the giants of the church’s history, delve into the riches of Scripture, the depth of the church’s traditions. Master their challenges, open yourself to the Spirit’s work, and learn how to risk yourself in the name of Christ.

But remember, that journey cannot be packaged and institutionalized, and contemporary theological education gives it little or no thought to it. If you are fortunate, you will find kindred spirits along the way and maybe even a mentor or two. Foster those relationships, look to God, and test the spirit of seminary where you enroll.

[i] Those already existed in the United Methodist Church, but they have spread across mainline denominations.

[ii] This is probably due in large part to the fact that seminaries have increasingly come to think of themselves, not as places for academic preparation, but as change-agents. This self-understanding has inevitably become wrapped itself around notions of “mission” and “mission” requires personnel.

martin-adams-_OZCl4XcpRw-unsplash-scaled.jpg