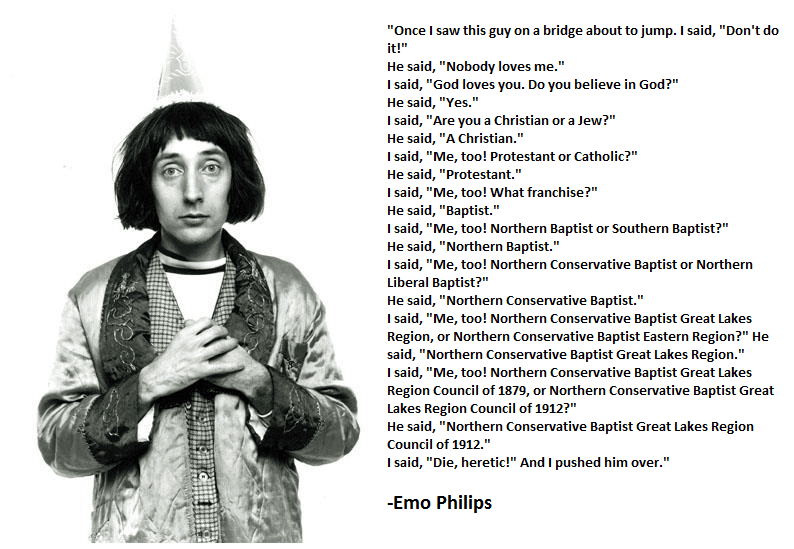

A favorite blogger, Aidan Kimel, posted a story describing what he describes as what happens “when ecumenism hits a wall”:

In truth, though, the story that Philips tells captures the temperament of contemporary discourse – and not just contemporary theological discourse, but political and social discourse as well.

We no longer possess a capacity for difference of opinion and perspective. We no longer acknowledge the inevitability of difference. And we have embraced a willful ignorance of the factors that account for those differences:

- The defects in our own perspective.

- The possible strengths of an alternative perspective.

- The differences traceable to age, race, and ethnicity.

- The complex forces of socialization at play in our families and communities.

- The process of maturation and our location on that journey.

- The countless factors that draw our attention to some issues and distract us from others.

- The priority we give to some goals.

- The lack of emphasis that we place on others.

- The complex factors that prompt us to look for collective solutions to some problems.

- And the complex factors that prompt us to look for individual solutions to others.

There are, of course, other factors that can account for differences of opinion that are less benign – prejudice, bigotry, and willful blindness, among them. But those factors, which lie at the margins of human behavior, have moved to the center of the explanations that we now offer as an explanation for the views of those with whom we differ.

The results have been devastating. The tendency to malign those who differ with us has made us intolerant and incapable of granting space for conversation. It has made us unreasonable, unrealistic, and uncharitable. Discourse itself is now little more than a series of countervailing accusations and, as a result, we have been made collectively stupid. We lack a capacity for nuance, for depth of analysis, and for ambiguity. We no longer allow time to process our differences, and we are unable to acknowledge that most solutions to the challenges we face require a less ideological, divergent solution.

When and how this state of affairs will change is difficult to say. One solution may be the retirement and death of old protagonists. The public maelstrom that passes for discourse revolves around polarizing figures that circle the same, unproductive set of alternatives. And that gerontocracy is incapable of letting go. But it is naïve to assume that a new generation of leaders will demonstrate a gift for deliberation that is free of the fixed points that have shaped the current debates.

What is needed is the one thing that is a product of the gift of deliberation itself: virtue. As one writer puts it:

A virtue is an excellent trait of character. It is a disposition, well entrenched in its possessor—something that, as we say, goes all the way down, unlike a habit such as being a tea-drinker—to notice, expect, value, feel, desire, choose, act, and react in certain characteristic ways. To possess a virtue is to be a certain sort of person with a certain complex mindset. A significant aspect of this mindset is the wholehearted acceptance of a distinctive range of considerations as reasons for action. An honest person cannot be identified simply as one who, for example, practices honest dealing and does not cheat. If such actions are done merely because the agent thinks that honesty is the best policy, or because they fear being caught out, rather than through recognising “To do otherwise would be dishonest” as the relevant reason, they are not the actions of an honest person. An honest person cannot be identified simply as one who, for example, tells the truth because it is the truth, for one can have the virtue of honesty without being tactless or indiscreet. The honest person recognises “That would be a lie” as a strong (though perhaps not overriding) reason for not making certain statements in certain circumstances, and gives due, but not overriding, weight to “That would be the truth” as a reason for making them.

An honest person’s reasons and choices with respect to honest and dishonest actions reflect her views about honesty, truth, and deception—but of course such views manifest themselves with respect to other actions, and to emotional reactions as well. Valuing honesty as she does, she chooses, where possible to work with honest people, to have honest friends, to bring up her children to be honest. She disapproves of, dislikes, deplores dishonesty, is not amused by certain tales of chicanery, despises or pities those who succeed through deception rather than thinking they have been clever, is unsurprised, or pleased (as appropriate) when honesty triumphs, is shocked or distressed when those near and dear to her do what is dishonest and so on. Given that a virtue is such a multi-track disposition, it would obviously be reckless to attribute one to an agent on the basis of a single observed action or even a series of similar actions, especially if you don’t know the agent’s reasons for doing as she did…

The daunting challenge inherent in this description of virtue is the recognition that it is not a trait that can be acquired overnight, and in order for virtue to take hold, it needs to be reasserted, over and over again, in the face of behaviors that militate against virtue. The good news is that anyone and everyone can commit themselves to its acquisition, given adequate time and dedication to the effort.

The first step in that effort is to divorce ourselves from the crazy-making environment in which we live.