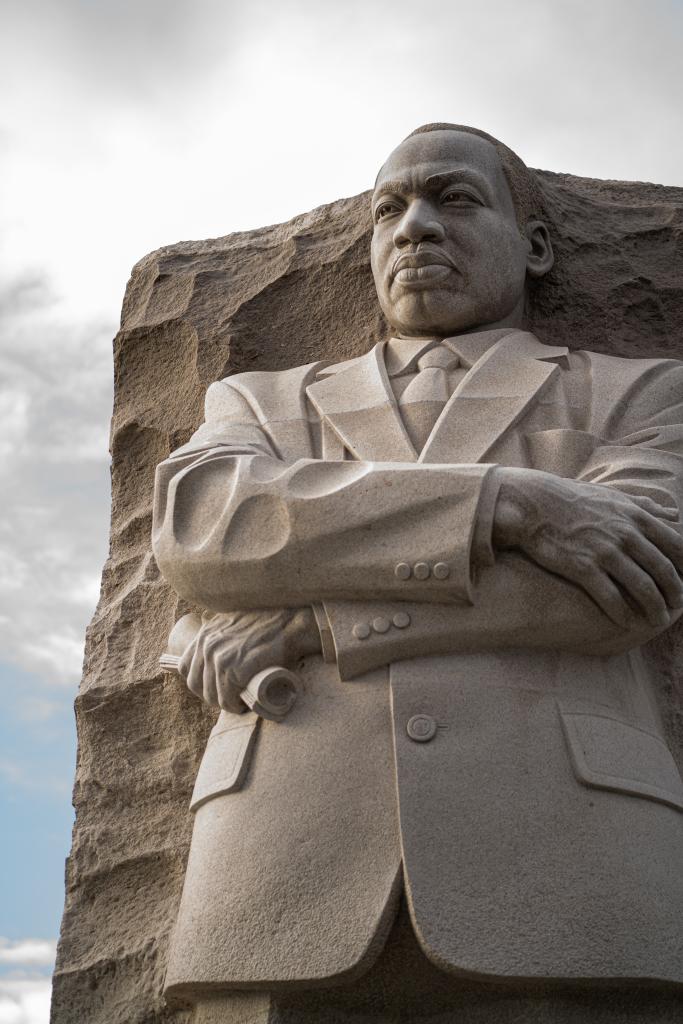

Years ago… I visited the Martin Luther King Center and purchased a children’s biography of King for my six year old daughter. This led to a collection of King biographies that over the years have grown in sophistication. When she was nine, she played on a frequent basis with a large number of other children in the cathedral close in Jerusalem. Among her friends was Jamie, a younger Canadian boy, and Alex, an American who had a reputation for being something of a bully. One day Jamie noticed Alex treat one of the other children pretty roughly and, at first, he was inclined to confront Alex. But, having done a quick body-mass comparison, Jamie concluded it was better to remain silent. Lindsay, with her well-honed sense of justice, said to her Canadian friend, “Jamie, go ahead and tell him what he did was wrong. Martin Luther King did — they killed him, of course —- but he did it anyway.” You have to admire her values, although she could learn something about the art of persuasion. (It is probably not a particularly good approach to lead with martyrdom!) And, yet, that is, in fact, the point.[1]

King died witnessing to his faith and its implications. Biblical allusions and images, pictures of God’s will for us, deeply theological assumptions about who we are – collectively and individually – are thread through his sermons, speeches, and writing.

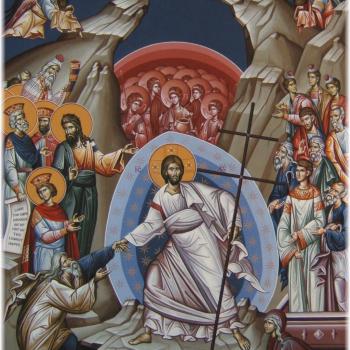

That approach to life’s challenges lies at the heart of what it means to be a martyr. In the first place, a martyr is a witness. But, in turn, the faithfulness of early witnesses to the Gospel gave it the meaning it has today: one who dies witnessing to their faith.

Both distinctions are worth bearing in mind, if you are a Christian. Where politics have supplanted witness and political categories have supplanted a deep contemplation of the will of God, there may be people who make sacrifices. But they aren’t martyrs.

[1] Frederick W. Schmidt, What God Wants for Your Life (San Francisco: Harper One, 2005): 82-83.

Photo by J. Amill Santiago on Unsplash