There have been countless articles and reflections on the meltdown at Mars Hill. Christianity Today featured a podcast which was one of the lengthier meditations on that story, but there were others worth reading (among them, read here and here). Both the massive popularity and the spectacular failure of that ministry justifies attention, even in parts of the church that are far from the non-denom world.

There is no need to cover the same territory discussed elsewhere. But there a handful of topics that bear further conversation across the larger church that doesn’t seem to be as prominent in those reviews.

One: Driscoll obviously spoke to a need that has largely gone unaddressed in the church.

There can be no doubt that the categories Driscoll used to characterize masculinity had little basis in Scripture, never mind the Christian tradition. And those categories not only distorted his ministry to men, they also had devastating implications for the women in his congregation.

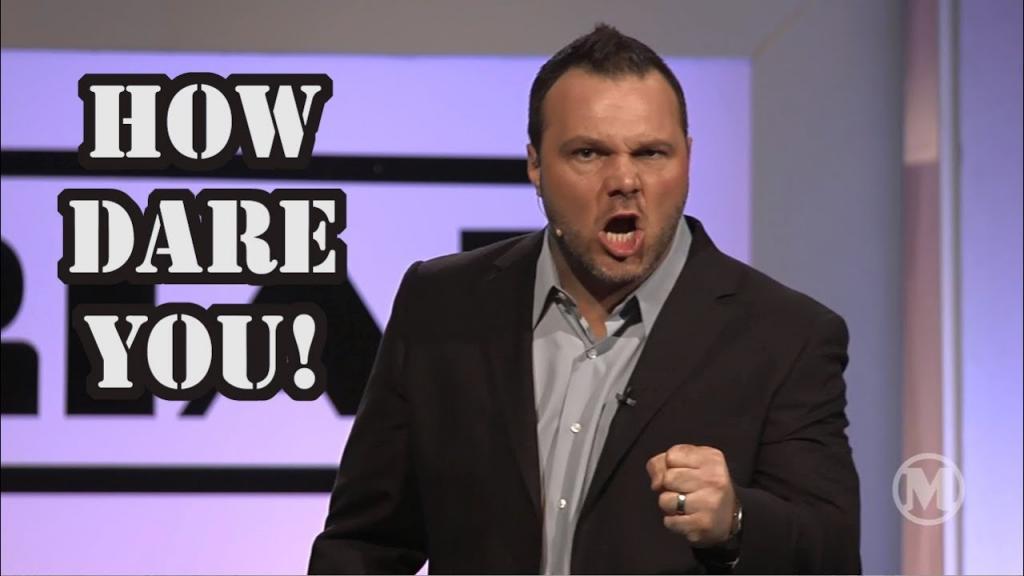

It is telling how deeply Driscoll was moved by the movie, Fight Club. The polarities in that movie present a false set of alternatives that far from compatible with Gospel. Yet it shaped both the tenor and the content of Driscoll’s ministry, and there can be little doubt that the Gospel was treated as little more than a thin veneer.

However, what commentators have failed to explore is the way in which Driscoll’s ministry spoke to the needs of men who were trying to connect what they believed about their faith with the demands that the world makes upon them on a weekly basis. That challenge deserves more work than we have devoted to it. Unreflective diatribes on “toxic masculinity” do little to help people.

It is also worth exploring why his ministry attracted women as well. Given the sexist and exploitative overtones to much of what Driscoll said, it is hard to understand the attraction that his message had for women – until one notes the emphasis that he placed upon the importance of the family and faith development. Those were both messages that people were not hearing elsewhere, and it suggests that there is healthier, lifegiving work to do.

Two: Understandably, most diagnoses of what went wrong at Mars Hill are predicated on a non-denom ecclesiology, but much of what went wrong at Mars Hill lies in that ecclesiology itself.

In short, things are bound to go wrong when someone owns a church.

Ultimately, of course, as a matter of legal record, someone always does. And, yes, mainline denominations often “own” the buildings where local congregations worship. It is also true that, based upon public records, it is difficult to know who “owned” Mars Hill, so I use the word loosely. But that said, Driscoll both planted the congregation at Mars Hill and dominated its leadership, so in all the ways that matter, he did own it.

Watching major non-denoms navigate the wake of failed leadership in a number of congregations, it is clear that both for non-denoms and long-term pastorates in other parts of the church, there are significant challenges when one person exercises a long-term influence over the life of a congregation. But the problems grow exponentially if that influence is accompanied by a sense of ownership over the church.

Churches of every kind are well-served by remembering that Jesus Christ is ultimately the Lord of the church. Both the metaphors of “body” and “bride” emphasize that reality and should deeply inform any healthy sense of spiritual authority.

Three: Clearly accountability was the other problem at Mars Hill.

The accountability issue flows naturally from the sense of ownership that Driscoll exercised over Mars Hill. It is also implicated in his theology of “call.” Having declared himself called to his ministry by God and having started a church that he owns, Driscoll was not accountable to anyone. Yes, he gathered people around him, but he was under no obligation to listen to them – and he didn’t.

The varied traditions of the church differ on the question of what a “call” to ministry requires. Each denomination has a somewhat different process, and each process has an integrity of its own. But what was clearly missing at Mars Hill was any element of communal discernment and the requisite accountability that is part and parcel of that discernment

Churches that incorporate that process of discernment into their approach to ordination should celebrate it and do everything that they can do to ensure that the process continues to be robust. Churches that don’t should grapple with the implications of its absence.

Bottom line: The life of Mars Hill may differ in many ways from the churches we attend and lead, but its experience has things to teach us.

It is common for mainline churches to ignore or despise what non-denoms do; and at other times, there are hints of jealousy in some of what is said about them. But those attitudes close us off to critical appraisals of what they do and don’t do well.