We draped a sheet across a metal trellis and called it a covered wagon. We used the sacrament table for Jane James’s bed. We let Elijah Able use the podium, and we put the choir in the cushioned seats by the piano and organ.

This was our Genesis meeting on Sunday, March 5th, 2000. We debuted my play I Am Jane to a diverse audience that included LDS apostle David B. Haight, whose ancestor had been in Jane’s 1847 pioneer company, Elder Alexander B. Morrison, who had written about the LDS Church in Africa, and Elder John Groberg, whose mission in Tonga was about to be the subject of a movie.

The audience was full. Newspapers had announced it, and we could not accommodate all who came. People were hungry to know more about Jane Elizabeth Manning James, portrayed in this debut by Denise Cutliff.

One audience member was a direct descendant of Jane James, but was bitter about how the Church had treated her parents. I doubt she liked the play, but I didn’t ask her. I quit looking for Jane’s descendants, assuming that all would be similarly bitter.

I was wrong.

Louis Duffy was not only friendly but eager to learn about the work we had done. Louis, Jane’s great great grandson, had inherited treasures from his ancestors, and understood their value. From his grandmother, Nettie James Leggroan, he had inherited the silver spoon broach she wore in her portrait before her early death from a heart condition. From Martha Stevens Perkins, granddaughter of enslaved pioneer Green Flake, he inherited a square of delicate embroidery—a small handkerchief, perhaps. From Jane herself, he inherited a map of the pioneer trek.

Darius Gray and I received a letter from Louis just after our black pioneer trilogy (Standing on the Promises) was published. He had noticed a couple of missionaries near his Los Angeles home—in an area where he had never seen missionaries—and invited them in. He told them that he descended from Mormon pioneers, and got the predictable, shocked look when he revealed that news—the look that says: “But you’re—well—BLACK!” Amazingly, one of the missionaries had seen my play, and asked Louis if he had ever heard of I Am Jane. He proceeded to tell Louis the plot. “That’s my great great grandmother!” Louis said. He then went online and found our books, which he ordered via express mail. A voracious reader, he read all three twice within a couple of weeks. Then he wrote to us.

We (Darius Gray and I) met him a few months later and felt instantly that we were all family. It would be many years before he would see I Am Jane, but by the time he did he was already deeply connected with those who portrayed his ancestors, particularly with Tamu Smith, who played Jane.

This is my brief interview with Louis:

1) How much did your mother tell you about Jane?

It seems to me that I have always known about Jane, but not a lot about personal details in regards to her early life. I do know that she was born a free person of color and that she lived with Joseph Smith until shortly before his death. The Pioneer Travel Map had always been on the walls of our home and my mom would often show me the route that the Mormons took to get to Utah. From what I remember, the map was passed on to Sylvester by his mother Jane. He gave it to my mom when she was in her mid-teens and I received it when my mom passed away. I donated it to the SLC Genesis group in memory of Jane and my mom.

2) How has learning more about Jane James affected your life?

Learning about Jane’s life story has simply ALTERED my life! I’ve become more empathic and less accusatory.

3) Tell a little about the friendships you’ve developed as Jane’s story has been told or monuments dedicated to her and to her posterity.

The friendships which I have thus far obtained from my associations with members of the LDS faith have proven to be everlasting and true in all manner of friendship. Yet, the acknowledgment and the dissolving of racial impediments is still a paramount concern of mine among the general population of Mormons. It’s beyond social norms and mores but holds strong religious-based teachings. And that needs to be changed.

4) You have a photo of a beautiful woman dressed in a cap and casual pioneer clothes. The photo was not labeled, but you always felt it was your great great grandmother. Jane’s identity was finally verified by a sculptor who took facial measurements and compared that photo with others of her. Could you talk about that?

The photo that I discovered of Jane was an amazing find. And I do believe that there is/was a spiritual guidance that directed me to that particular picture. Yes, the voice did say to me: “I Am Jane, and I am your great great grandmother.” The second time that I felt Jane’s presence was at the cemetery when we dedicated the headstone in memory of the children and grandchildren. Jane was there, admiring and thanking all of us for our love. The third time I experience Jane’s presence was at the June – 2010 event of “I Am Jane.” Towards the end of the play when Jane is making her transition from life to death, I also felt my mom’s presence. They were together! As you know, they passed away on the same date – April 16th. I cried, I couldn’t help it. I thought of Sylvester, too.

I always intended I Am Jane to be an intimate, small play, suggesting Jane’s unpretentious life. What I’ve found after over a decade of various runs of the play is that Jane’s question to President John Taylor—“Is there no blessing for me?”—resonates with all of us as we contemplate our most difficult moments. Her faith and tenacity offer us strength and a vision of grace.

As she speaks of the long, mostly barefoot trek she and her family made from Buffalo, New York to Nauvoo, Illinois, she gives hard details, but concludes with gratitude:

We walked until our shoes were worn out, and our feet became sore and cracked open and bled until you could see the whole print of our feet with blood on the ground. We stopped and united in prayer to the Lord; we asked God the Eternal Father to heal our feet. Our prayers were answered and our feet were healed forthwith. . .[W]e went on our way rejoicing, singing hymns, and thanking God for his infinite goodness and mercy to us–in blessing us as he had, protecting us from all harm, answering our prayers, and healing our feet.

She describes the privations of life in pioneer Utah, but again concludes with praises to God: “Oh how I suffered of cold and hunger, and the keenest of all was to hear my little ones crying for bread, and I had none to give them; but in all, the Lord was with us and gave us grace and faith to stand at all.”

All of these lines are in the play. I put as much of it into her own words as I could. I did as I knew she would want, and included her final testimony in the final moments:

I have seen my husband and all my children but two laid away in the silent tomb. But the Lord protects me and takes good care of me in my helpless condition. And I want to say right here that my faith in the gospel of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is as strong today–nay it is if possible stronger–than it was the day I was first baptized. I pay my tithes and offerings, keep the Word of Wisdom. I go to bed early and arise early. I try in my feeble way to set a good example to all.

As the show ends, Jane comes onstage after her death, and Elijah Abel addresses the audience: “Now you all know that many things have changed for us since the days of this story. There’s still struggles, don’t get me wrong. But I haven’t wearied of the struggles. Have you, Jane?”

Jane answers, “Wearied? Why, I’m stronger than I been in years! Besides which, I can see like my eyes was new! All these folks are remembering me–I feel near resurrected!”

Elijah says he’s feeling rather strong himself, and leads the cast in the traditional spiritual “I Don’t Feel No Ways Tired.”

I don’t feel no ways tired—

I’ve come too far from where I started from.

Nobody told me the road would be easy

I don’t believe He brought me this far

Just to leave me.

I knew it was just the right song.

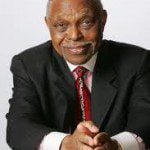

And now, here we are in 2013. What would Jane say of the new church statement on race and priesthood? I suspect she would echo Dr. Cecil “Chip” Murray, retired pastor of the First A.M.E. Church of Los Angeles, who replied to my email about it thus: “Yes, I have tracked the history of the ‘curse of Cain,’ and having been exposed to the Mormon Church at its best, looked anxiously to that day when the word would become flesh. That day has come. . .Now the Church will surge to the top, as its hindrance is removed and its positive programs are sweeping the planet. Nothing can stop it now!”

Both Jane and Pastor Murray saw the church at its worst. Jane petitioned time and again for temple blessings and was denied. Pastor Murray was told by two Mormon army mates that he was “cursed.” His response, years later, was simply, “Of course I would never believe that.” He knew who he was.

And Jane knew who she was. Louis Duffy doubtless expresses just what Jane would say in his response to the statement: “I am pleased that the official word is being shared and I’m hoping that the masses will acknowledge the declaration and most importantly, immediately put it to practice.”

(A portion of this essay was previously published at By Common Consent.)