In The Everlasting Man, G.K. Chesterton said that the Christian faith has a peculiar character. Often in history (he writes) it seemed as though the “whole soul seemed to have gone out of Christianity; and almost every man in his heart expected its end.” But every man, it seemed, would be wrong.

“Christendom has had a series of revolutions and in each one of them Christianity has died,” Chesterton wrote. “Christianity has died many times and risen again; for it had a god who knew the way out of the grave.”

I thought about that line as I watched The Jesus Revolution, out in wide release today.

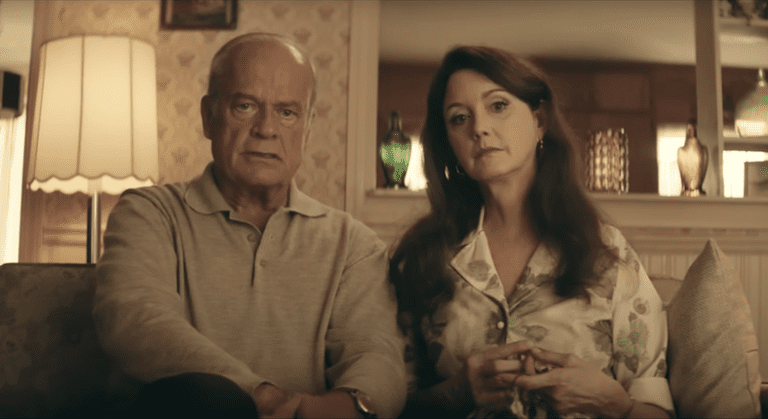

The movie whisks us to Southern California in the waning days of the counterculture. Janis Joplin and Jimmy Hendrix are still alive. Author Timothy Leary is encouraging youth to “Turn on, tune in and drop out.” Flower power seems like the power right now—and the Rev. Chuck Smith (played by Kelsey Grammar) doesn’t like it one bit.

He fumes as he watches demonstrations on the news in his Costa Mesa home. He preaches against the movement from the pulpit of his dwindling congregation. His own daughter, Janette, is sympathetic to the movement. But Chuck just thinks all those hippies could use a good bath. He snidely suggests to Janette that she bring him one—like one might bring home a lost puppy—so he can see what they really want.

So she does.

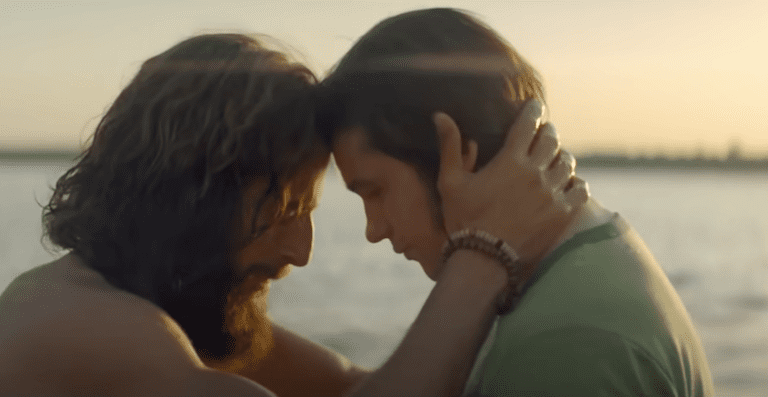

That hippie is Lonnie Frisbee (Jonathan Roumie), who’s slowly working his way south from San Francisco, the epicenter of the Flower Power movement. But disillusioned by the ultimate emptiness of the counterculture, Lonnie’s found something he considers far better: Jesus. And he’s determined to share the Good News with anyone who’ll listen.

He tells Chuck that America’s youth are indeed lost, mired in sex and drugs. But he suggests that they’re looking for “all the right things, just in all the wrong places.” They’re looking for justice. Love. Meaning.

“It’s a quest,” Lonnie says.

“For what?” asks Chuck.

“For God,” Lonnie says. “There is an entire generation right now searching for God.”

The movie thus begins its exploration of an unexpected resurgence—or rebirth, perhaps Chesterton would say—of Christian faith. Lonnie and Chuck would ultimately co-lead a massive religious revival that gave rise to new sprawling evangelical denominations, contemporary Christian music and a new way of thinking about and worshipping God.

The Jesus Revolution focuses on Chuck, Lonnie and a young doodler named Greg Laurie (Joel Courtney), a straight-laced high schooler who dives into the counterculture and nearly drowns before finding Lonnie’s own Christ-based path. The real-life Laurie, of course, later became a Christian influencer in his own right, leading Harvest Christian Fellowship and authoring scores of books.

The movie, directed by Jon Erwin and Brent McCorkle (and based on Laurie’s own book about the movement) takes us through the movement’s exciting early days and growing pains, including Chuck’s and Lonnie’s painful split. And I thought it was pretty great.

Not every critic has warmed to the movie. I’d imagine for some, the whole Jesus thing in The Jesus Revolution makes it a non-starter. But for me it worked. It worked so well, in fact, that I’d say this is just about the best “Christian movie”—that is, a movie more or less made inside the faith-based film industry—that I’ve ever seen. Anchored by strong performances by Grammer, Courtney and the ever-interesting Roumie (who plays Jesus in The Chosen and makes a bit of a winking reference to that in the film), The Jesus Revolution transcends its historical trappings and shows us how faith moves in unexpected ways.

Certainly, The Jesus Revolution hints at the flaws found in its leaders—and the mistakes some made along the way. But that, too, is strangely encouraging. After all, Christianity isn’t really about Chuck Smith or Lonnie Frisbee. It’s not about Martin Luther or Martin Luther King Jr. it’s about Jesus—a guy who Himself gathered together plenty of imperfect people and taught them a higher calling in spite of those imperfections.

Despite its historical underpinnings, The Jesus Revolution feels incredibly, and in some ways unexpectedly, timely. After all, the age in which the movie takes place isn’t so different from our own. Studies suggest that Christianity is losing its cultural oomph. Churches are emptying. Faith, especially among younger Americans, is statistically dwindling.

And yet, just a week or so before The Jesus Revolution’s nationwide release, we heard about a strange happening in Kentucky’s Asbury University. For nearly two weeks, people flooded both the school’s chapel and its campus, with many reporting that their faith has been newly energized. Gracie Turner, a senior at Asbury, told Fox News that she’d not truly prayed for years until her love of God was rekindled during what some are calling the Asbury Revival.

“It felt like God was telling me this is what you’ve been missing,” she said.

That’s the core message of The Jesus Revolution, too: Millions found what they had been missing—lost in the counterculture’s own misleading messages.

The movie deftly sandwiches its narrative between two famous covers of Time magazine. Near the beginning, Chuck brandishes a 1966 mag that darkly asks, “Is God Dead?” At the end, the movie answers its own question with Time’s 1971 “The Jesus Revolution” cover.

Christianity has a God that knows the way out of the grave.