My late friend and mentor Ivan Kauffman once described himself as “probably the only living person who speaks both fluent Mennonite and fluent Catholic.” If these words were true when he first wrote them, a handful of others, myself included, would eventually follow him to the same ecclesial bilingualism and, if not quite an official dual citizenship, an inescapably dual identity as self-described Mennonite Catholics.

More precisely, 10 years ago today, with Ivan standing behind me as my sponsor, I professed the Catholic Church to be my home. That moment was both the end of a long period of exploration and the beginning of a long (surely lifelong) period of acclimation. I’ve often thought of the whole experience as something analogous to expatriation – perhaps no less appropriate a model than even the language of conversion. I strongly relate to Ivan’s self-description as “a cultural, historical, theological and institutional translator between these two very different worlds.” Like Ivan, I feel most at home among those familiar with both worlds; unlike Ivan and his wife Lois, who together blazed a path between these two worlds that I and a few others would later follow, it was in large part the already-existing presence of an expat community from my ecclesial homeland – people who understand with equal depth both the attractions that drew me to my adopted home and the moments of homesickness and culture shock that every expatriate knows – that made it possible for me to find a home in the Catholic Church.

And there certainly have been culture shocks, both big and small. A trivial yet oddly frequent one is my observation of a widespread tendency for those who arrive earliest for Mass to gravitate to the ends of pews, forcing any relative latecomers to either search for an empty pew or climb over someone to find a seat. The phenomenon puzzles me to this day; anytime I’ve commented on it, I’ve been met with a few personal excuses (usually claustrophobia) for why the responder feels the need to do it, but nothing that explains why it’s such a common habit as to be observable in virtually every parish I’ve been to.

Another that was less apparent when I first began regularly attending Mass in Haiti, but became noticeable as I continued to do so back in the US, is congregational singing. Being accustomed to robust, often a cappella, four-part hymn-singing sets high expectations for the musical participation of one’s fellow congregants. Invariably, the first thing I do whenever I join a new parish is to join the choir – not just because I love to sing or because it’s a contribution I can offer to the parish’s life and worship (though both are true), but just as much to feel the comforting familiarity of other people singing strongly around me, rather than feeling as though I’m singing a solo from the pew.

But my most serious and troubling Catholic culture shock has to do with a deep-running and widespread impulse that I’ve struggled to get my mind around, to grasp its logic and even to name it adequately, since I entered the Catholic Church: an impulse toward cultural and institutional upward mobility, or to put it more boldly, a libido dominandi – lust to rule. It doesn’t always appear as insidious as that sounds, which is precisely its seductive power. More often than not, it comes dressed up in good intentions such as promoting the common good and building the Kingdom of God. And many Catholics simply seem to be unable to conceive of any way of pursuing these good ends that doesn’t involve the pursuit of governing power and social privilege, seeing top-down control as an ideal, if not a necessity, for influencing society – always out of love, or so they manage to convince themselves. And I, for my part, can’t not see such pursuits as inevitably compromising at best, easily leading to gross distortions if not outright contradictions of the very gospel we’re aiming to spread – what Mennonite author Donald Kraybill would call right-side-up detours away from the upside-down kingdom.

I come from a culture of counterculture, forged in the harsh crucible of experience on the receiving end of Catholic and Protestant entanglements with governing power at their ugliest – a culture that, no matter how assimilated some parts of it become to the surrounding cultures in which it lives, always instinctively chafes against power and privilege, and has struggled to reconcile its own increased social acceptance and admiration with its ancestral belief that persecution was the mark of the true Church, now stressing all the more strongly in the absence of martyrdom that Christians must always remain a “sign of contradiction” within the world.

In H. Richard Niebuhr’s taxonomy, I migrated from a deeply “Christ against culture” communion to a deeply “Christ of culture” one. This remains a source of deep tension for me, and it is in this sense especially that I resonate with Ivan Kauffman’s self-observation, “The more Catholic I have become, the more deeply Mennonite I realize I actually am.” This Christ-of-culture, libido dominandi, upwardly mobile impulse, especially in the ways it plays out with Catholics in positions of public influence, is why I sometimes feel embarrassed to admit to being Catholic. I had certainly wrestled for a considerable time with the Catholic Church’s historical ties to power before joining it, but sometimes I wonder, if I had fully perceived how deep and broad and ideologically cross-cutting (yes, I have observed something of a theocratic left) the impulse goes, if I had known all the things I would hear said in its defense, even at times among people I otherwise hold many values in common with (to the point of insistently taking as a legitimate point of debate whether it’s morally acceptable to “burn heretics”!), whether I would still have joined.

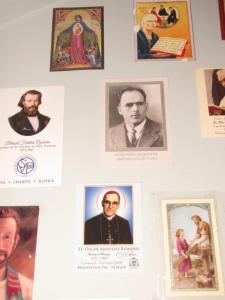

The more strongly I feel this tension, the more tightly I cling to those witnesses within the Catholic tradition that

stand as countercurrents against the pull of the libido dominandi impulse, whose very existence is a much-needed reminder that I was never alone in the tension, that the tension already existed in the tradition itself: the resolutely countercultural example of Catholic Worker founders Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin; the prophetic defiance of violence by modern martyrs of conscience such as Blessed Franz Jagerstatter and St. Oscar Romero; the unearthed witness of ancient conscientious objector saints such as Martin of Tours (that most ironic patron saint of soldiers) and Marcellus of Tangier; the great cloud of witnesses represented in my co-blogger Mark Gordon’s Novena for Peace. I’m encouraged by ongoing work such as that of the Catholic Nonviolence Initiative – a project that includes my fellow expatriate Gerald Schlabach, whose writing also continues to reground my own vision of the meaning of catholicity. As I’ve experienced a wide spectrum of Catholic parish life from dry bean-counting to vibrant discipleship, I’ve continued to cling to memories of and connections to those communities that first showed me what it meant to live the Eucharist: St. François Xavier in Désarmes, Haiti; St. Patrick’s Cathedral in El Paso, Texas; St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota. If I had not seen that there is a place for such lives and voices and works as these within the living Catholic tradition, I most certainly could not have joined it.

When I did take my oath of citizenship, such as it was – publicly and personally professing belief in “all that the holy Catholic Church believes, teaches, and proclaims to be revealed by God” – I saw in that phrase a living conversation embracing all the above witnesses and many, many more within an ecclesial big tent. I hoped then, and still hope now, that I have a contribution to make within this conversation that I couldn’t have made from outside of it, even though – or perhaps because – my now-fluent Catholic is still spoken with a heavily Mennonite accent.