Theosis.

While the word has made a comeback in certain theological circles, it remains relatively unknown by the ordinary Christian. When I tell people that it means ‘god making’ or ‘deification’, many people look at me as if I said something horribly wrong. They act as if when I proclaim such a teaching, I must be a heretic. Even some who are familiar with the term and the background associated with it get uncomfortable when it is mentioned. It is because there are many ways the word can be misunderstood. The general suspicion is that anyone who uses it is doing so wrongly. Even when I quote the catechism, showing its doctrinal status, I am told I must be misinterpreting it – before I discuss its meaning.[1] The very fact that I bring it up is enough for some to condemn me. It sounds odd, and that’s all it takes for to issue an anathema. And yet theosis plays a major part in the Eastern theological and spiritual tradition; if I were I ignore it, I would ignore a part of who and what I am.

In order to help people understand what theosis is, and what it actually means, I think it is important to do an introductory piece on the term, showing its scriptural and patristic sources, but also demonstrating what exactly it is supposed to mean so that people do not have to be concerned with the word. When they do, hopefully they will understand not only why deification is the goal of the Christian life; indeed, it can be said that any end for us but deification would end up unsatisfactory, because it would end up a dead-end.

Scripture has a few passages which tradition sees as the reference points on theosis from revelation. Each one is interesting, and each one, when brought forth, will have readers trying to downplay what is contained in them.

“I say, “You are gods, sons of the Most High, all of you” (Psalms 82:6). [This text, which is used by Jesus to defend himself, indicates that we are to be brought into a relationship with God, so that we are able to be called God’s sons and therefore, if sons of God, gods].

“Yet the number of the people of Israel shall be like the sand of the sea, which can be neither measured nor numbered; and in the place where it was said to them, ‘You are not my people,’ it shall be said to them, ‘Sons of the living God’” (Hosea 1:10). [Like Psalms 82:6, this verse indicates the special status of sons (and daughters) of God given to Israel, God’s chosen; once again, the end result of this would be to indicate someone is a ‘god’ as well].

“Jesus answered them, ‘Is it not written in your law, `I said, you are gods’? If he called them gods to whom the word of God came (and scripture cannot be broken), do you say of him whom the Father consecrated and sent into the world, `You are blaspheming,’ because I said, `I am the Son of God’” (John 10:34-6). [Here we find Jesus using the Psalms for a specific purpose; he is asking why is it blasphemous for him to be calling himself a son of God if Scripture has already given that name to those in Israel? Of course, Christian theology would later point out it is in and through Christ we find our way to the Father and become adopted as sons of God, and so it is why we can call others gods].

“For we are God’s fellow workers” (1 Cor. 3:9a). [We have been raised up in grace so that we can and do work with God; we are not just being saved, but we are being given back our dignity so that we can work with God].

“My little children, with whom I am again in travail until Christ be formed in you!”(Gal. 4:19). [As Christ is formed in us, through grace, we partake of what Christ is, that is, we partake of his divine sonship].

“His divine power has granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness, through the knowledge of him who called us to his own glory and excellence, by which he has granted to us his precious and very great promises, that through these you may escape from the corruption that is in the world because of passion, and become partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:3-4). [This is a very important passage which tells us that we shall have a place in the divine life, because we will participate in it; this is because of grace, and not due to our nature. Nonetheless, our nature must be of such that we are open to the possibility, instead of closed off to itself].

If all we had was these texts, to be sure, one could find many ways to interpret them. But the living tradition of the Church has found them to be indicative of who we are supposed to be, and that is, to be participants in the divine nature, sharing in with the divine life, so that we can be said to be ‘gods’, not by nature, but by grace.

The question which we should ask is one which is often not asked; it is a simple this: what exactly is a god, and what do we mean by being made a god? When we look into this, we will understand that patristics, in saying we are to become god, are saying something different with the word god than what we take it to mean today, and they are following the ancient understanding of the word – what we point to as God, the Holy Divine Trinity, was in many patristic source seen as something beyond Godhood though possessing everything which is normally ascribed to the gods, and thus best described as god.[2]

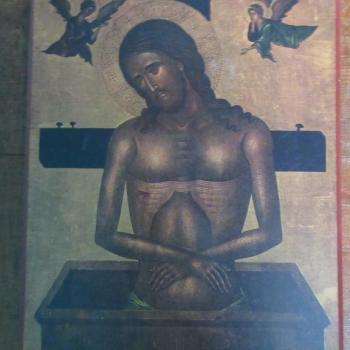

Perhaps the most important aspect of godhood was their status as immortals; this is exactly what St. Athanasius understood we needed and said God provided to us by becoming human; this is what he was saying with his famous dictum, “For He was made man that we might be made God.”[3] This is confirmed by what he says afterward, in what is less often quoted: “and He manifested Himself by a body that we might receive the idea of the unseen Father; and He endured the insolence of men so that we might inherit immortality.”[4] Elsewhere, St Athanasius proclaimed that our sin has compelled us to non-being, which closed us off from the immortality of God. Jesus, as our savior, was to help us become immortal, which is what God planned for us from the beginning:

For man is by nature mortal, inasmuch as he is made out of what is not; but by reason of his likeness to Him that is (and if he still preserved this likeness by keeping Him in his knowledge) he would stay his natural corruption, and remain incorrupt; as Wisdom says: “The taking heed to His laws is the assurance of immortality;” but being incorrupt, he would live henceforth as God, to which I suppose the divine Scripture refers, when it says: “I have said ye are gods, and ye are all sons of the most Highest; but ye die like men, and fall as one of the princes.”[5]

Footnotes

[1] “The Word became flesh to make us ‘partakers of the divine nature’: ‘For this is why the Word became man, and the Son of God became the Son of man: so that man, by entering into communion with the Word and thus receiving divine sonship, might become a son of God.’ ‘For the Son of God became man so that we might become God.’ ‘The only-begotten Son of God, wanting to make us sharers in his divinity, assumed our nature, so that he, made man, might make men gods.’ Catechism of the Catholic Church, ¶ 460.

[2] The word used for god is theos (θεος); some believed it to be derived from theoreo (θεωρέω), “to look, view, behold,” because the gods were those who looked down upon the world.

[3] St Athanasius, “On the Incarnation” in NPNF2(4) ¶ 54. 3.

[4] Ibid. ¶ 54. 3.

[5] Ibid. ¶ 4. 6 The relationship of theosis to being in the image and likeness of God is important, though will not be dealt here in any great length.