I am an American. I am also an American citizen, which is not exactly the same as being American. I was born in Pittsburgh. I spent 9 years in St. Louis, 10 years in Northern and Central California, and I have been in Houston for 3 years now. I have no intention of denying my American patrimony. I have no intention of leaving the United States.

in Pittsburgh. I spent 9 years in St. Louis, 10 years in Northern and Central California, and I have been in Houston for 3 years now. I have no intention of denying my American patrimony. I have no intention of leaving the United States.

I am patriotic when it comes to my country. I am not comfortable with the current State of my country. A country (patria) is distinct from the State (civitas). Following Pope John Paul II and St. Josemaría Escrivá, I embrace patriotism as a virtue; I abhor nationalism.

I am not turned off by the sight of the American flag. The flag, for me, represents the totality of the American reality. The very patrimony handed on to me is signified by that flag. It encompasses the deepest and most lasting realities of American culture, such as language, religion, culinary traditions, communication, education and infrastructure, though it also symbolizes those more transitory and fluctuating realities such as economic and political policy. These latter elements are not America. They are not even the most important aspects of America.

Politics, be it domestic or foreign, operates at a secondary level. It is not un-American to critique these policies, just as it was not un-Russian or un-Polish to critique statist socialism during the 20th century. Politics is in flux. Economics is in flux. It is true that they influence culture, but the relationship is not symmetrical. States rise and fall. Culture subsists beyond. Culturally, I am an American. Forever.

The American flag predates the current power structures of the United States, which rose rapidly after World War II. The American flag predates the consolidation of local markets into a national economy, which is not as “free” as it claims, and it most certainly predates the Leviathan of global capitalism.

The flag itself is a contradiction. It bears thirteen stripes, symbolizing the original colonies whose local policies and regional identities were joined loosely as a confederacy. The fifty stars symbolize the forced union of states under a federal mantel (hence, the stars in isolation serve as a maritime flag). I believe the true America is more stripes than stars. But I’ll take the stars. The flag is forever a symbol of the tension between local, independent traditions and a mass-scale political and ecnonomic unity.

The flag, to my recollection, has been displayed in four posts at Vox Nova. Michael Iafrate, Katerina, Feddie and Nate Wildermuth have used the flag in varying contexts. Iafrate and Feddie particularly have had to weather the storm of criticism from those who did not like the manner in which they portrayed and contextualized the image of the flag. The flag, it seems, represents different things in the minds of different people. Deciding what the flag represents appears to be a point of contention. Could it be that the tension it embodies in itself with its stars and stripes is indicative of the tension Americans experience among themselves when discussing what the flag represents. If so, then the flag is an apt and resilient symbol of the deepest and shallowest currents within America.

Those Americans who burn the flag, to me, often appear to confuse the flag with the political and military machinery of the United States. This is the same error, I think, that is made when the flags suddenly come out on the Fourth of July, as if the flag represents political independence. Either way, the flag is taken primarily as political tool or gesture. The fact that Title 4 of the United States Code outlines federal laws for flag etiquette compounds the difficulty in understanding that the flag is a primarily a cultural, not a political or legal, entity.

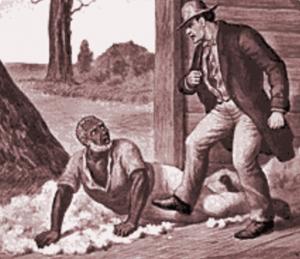

When I see the flag, I am reminded of the glory and the sins in the history of America. Patriotism is not only pride in one’s country (not necessarily in one’s State), but it is also criticism of the history of that culture. And there is plenty to be critical of in American history! But an American ought to be cautious in conducting this necessary criticism. After all, the very vantage point, language, resources and means of this criticism have been supplied by American culture!

To love America is appropriate for an American if by love we mean familial affection for our patrimony (patrimony comes from the Latin word for country, patria, which comes from the Latin word for father, pater). For an American to hate this patrimony, I think, is self-defeating and absurd. For an American to criticism his/her government is not necessarily unpatriotic, nor is it anti-American. To refrain from such criticism, I think, is unfreedom.

My flag is not my government. My flag encompasses that government, yes. But the flag more foundationally encompasses my culture. God, bless America? Please, Lord. God, bless the United States? That’s a different request.