We are entering the astrological sign of Scorpio, when our thoughts turn naturally towards death. Acknowledging the reality of death is something we do – and do not. Most of us are content to hover somewhere between theoretical acceptance and ignoring it. Some of us have relatives or friends who die when we are in our teens or twenties and we have to face up to death and grieving early on. For many of us though, it is only when we approach our forties and fifties that death starts to intrude. We may lose beloved parents and spiritual elders, and we may find that people of our own generation develop illnesses and die, sometimes many years before they or we expect it.

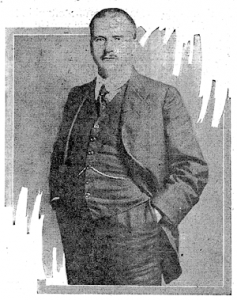

When he reached mid-life, the famous psychologist Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) wrote his thoughts about death in his personal journal The Red Book.

We need the coldness of death to see clearly. … If I accept death, then my tree greens, since dying increases life. If I plunge into the death encompassing the world, then my buds break open. How much our life needs death!

Joy at the smallest things comes to you only when you have accepted death. … If you accept death, it is altogether like a frosty night and an anxious misgiving, but a frosty night in a vineyard full of sweet grapes. You will soon take pleasure in your wealth. Death ripens. One needs death to be able to harvest the fruit. Without death, life would be meaningless, since the long-lasting rises again and denies its own meaning. To be, and to enjoy your being, you need death, and limitation enables you to fulfill your being.

Carl Gustav Jung, The Red Book: Liber Novus, 2009 ed., 274-275.

He believed that facing up to the reality of the finite human life span was good. Death can help us appreciate life.

Consciousness beyond the body

Most Pagans share the belief that death is not the end of existence. As Pagans, we are the heirs of the ancient mystery traditions. One of the purposes of the initiatory processes of the Pagan mystery traditions was to teach the reality of life after death. The initiate was exposed to ritual and symbols that caused inner change and conveyed messages about the enduring self. This is not the ‘I’ that has built up as a result of the experiences of a single incarnation, but something deeper, wider, and without boundaries.

What is this type of consciousness? At times we catch glimpses, tastes, experiences of it. In our deepest meditations, when alone in Nature, and sometimes in intense moments of love, sex, grief, initiation. If we are fortunate, we may have had spiritual experiences that show us that the body is not the boundary of our existence; that the way our sensory mechanisms perceive time and space are but temporary constructs, a take on reality conveyed within the constraints of our sensory systems and their capabilities. Experiences of synchronicity, telepathy, precognitive dreams, supernatural encounters, and out-of-the-body experiences, such as flying dreams, all enable us to understand that our consciousness and sense of self can separate from the physical vehicle of the body.

Near-death experiences, for many of us who have had them, can convey knowledge that gives an intimation of what the mysteries have taught – that consciousness can exist beyond the body. This type of experience is experiential and individual. It cannot convince someone who has not had it. It is not something that can be conveyed through words and rational argument; nor is it emotional. It is not about wish-fulfillment and finding some shield against the recognition our own mortality. It is about experiences that are real, ineffable, profound and life-changing.

Carl Jung’s near-death experience

Carl Gustav Jung had such an experience in 1944 when he was 68. He had suffered that common hazard of older life – a fall on the winter ice. He slipped and broke his fibula. Then, ten days later in hospital, he suffered a heart attack and began to die. Suddenly, he found himself floating 1,000 miles above the Earth. Seas and continents shimmered below him and he could make out the Arabian desert and the snow-tipped Himalayan mountains of northern India, a perspective that had yet to be photographed through space flight. Then a huge black monolithic structure came into view. He sensed that it was a temple, and at the entrance he saw a Hindu guru sitting in a lotus position. Jung felt his earthly existence being stripped away, until what remained was his essential self, the core of his being. He was about to go further and enter the temple, when his doctor appeared in the vision and told him that his departure was premature; many were demanding his return. Jung was immensely disappointed when almost immediately the vision ended.

The experience had a profound effect on him. The depression and pessimism that he had experienced during World War Two vanished. He decided to give up his university post and to dedicate himself to his final important work – his researches on alchemy, religion and Gnosticism. He was determined to make use of the time that had been given to him and the last seventeen years of his life from 68 to 85 were some of his most productive.

‘I’ and the body are not the same

We do not all have traumatic events like near-death experiences to help us focus on what is really important to us, but the spiritual experiences of transcendence that many of us find in ritual and meditation play a similar role in teaching us that ‘I’ and the body are not the same. We are privileged in having through our Pagan practice routes to such experiences that can help us begin to accept the inescapable reality of being a conscious being in a physical body. At Samhain, we acknowledge that the body grows and then decays. As we say in Wicca this is, ‘…age and fate against which we are powerless.’ But we remember also the promise of the Goddess:

‘Mine is the ecstasy of the spirit… and beyond death I bring peace and freedom and reunion with those who have gone before.’

So as we approach Samhain we honor the cycle of death, rebirth, and new life; and we honor the memory of those who have passed through the veil. We honor too the gift of life, that most precious of gifts, and we seek to drink of the cup of the wine of life to the full so that no precious drop is ever wasted.